It’s a well-known fact that, at some point in the 2000s, the number of humans living in urban areas eclipsed the number living in rural areas. Meanwhile, those machinations of industry and recreation that enable humans to exploit and enjoy natural resources leave fewer and fewer places on earth undisturbed. Philosophers such as Timothy Morton argue for abandoning the concept of “nature” altogether, in order to reach a more realistic understanding of ecology—one in which “the environment” does not stop at city limits or recede in the presence of architecture, but proceeds to encompass the messy mesh of organic and inorganic, living and nonliving, animal and vegetable and mineral and chemical realms in which everything in the world exists.

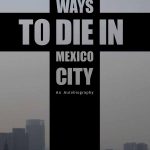

In this context, Several Ways to Die in Mexico City: An Autobiography is environmentalist literature. Refreshingly, though, Kurt Hollander’s brand of environmentalism disregards the typical hallmarks of that tradition, its bucolic ideals, and calls for grassroots organizing and, crucially, environmentalism’s focus on the more sparsely populated places on the planet. Instead of unquestioningly celebrating nature and bemoaning man’s impact on its life-giving agents, Hollander, a native New Yorker who has lived in the Mexican capital for more than two decades, examines our relationship with our surroundings through a darker prism—a paranoid stream of facts and figures, descriptions of Aztec cannibalism and cosmopolitan gut flora, reflections on his own unsentimental march toward death.

While many great environmental writings illuminate the ways in which life forms weave together in a delicate dance of existence, Hollander recognizes the ubiquitous potential for death as he picks through the tangle of elements in his daily urban environment that are conspiring to kill him. This, then, is environmental writing from a nearly post-environmentalist perspective: its urgency issues not from the fact that humans exist as part of an elaborate tapestry, but from the fact that we’ve poisoned the tapestry so much that it threatens to envelop and smother us.

Hollander’s concerns resemble those of many environmentalists—pollution, deforestation, over-exploitation of resources—and his naturalist’s sense of interconnectedness lets him move smoothly from aquifers to amoebas, conquistadors to high-fructose corn syrup. But, less commonly for the genre, he aims not to offer counsel but to map the many mortal pathways of his own environment and spread them out on the table for us to examine. The foundational chapters of Several Ways to Die are titled Air, Food, Water, and Alcohol; each...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in