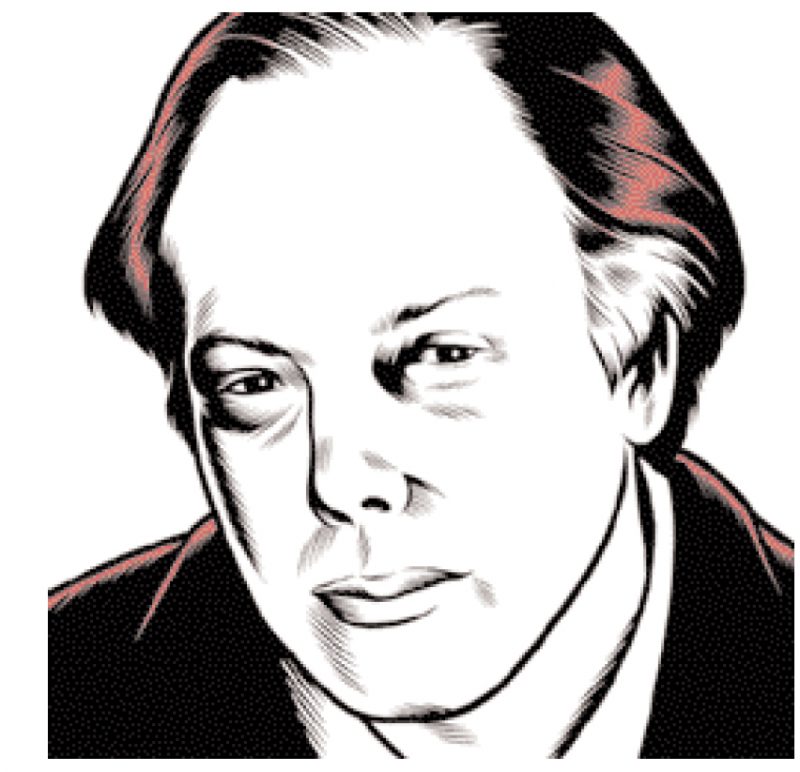

Some time ago I found myself writing about the legendary outlaw Dick Turpin and his ill-fated, semi-abandoned grave off in the city of York. As such, I don’t think it redundant to write about another grave, near Turpin’s, that marks the resting place of one of his contemporaries, a person for whom I have always felt a special affection. After all, I did spend two (now very distant) years of my life, from 1975 to 1977, translating into Spanish the approximately 800 diabolically complex pages of his magnum opus, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman. Better known simply by its narrator’s name, the book was originally published in serial form from 1760 to 1767, and its author, the Englishman Laurence Sterne (who, as fate would have it, was born in Ireland), was doubtless one of the sharpest, wittiest, and truly comical men ever known to the world of letters. For that same reason, I think I can safely say there is no other novel in existence that can be considered anywhere near as Cervantine as Sterne’s. Despite the fact that Spain’s political, academic, and literary authorities would strenuously disagree, and despite the fact that Cervantes is still miraculously considered to be the Spanish writer par excellence, the majority of Spain’s novelistic output since Cervantes has been scrupulously anti-Cervantine. In other words, it has been realistic (those who call the Quixote a “realistic” work should forever close their interpretative mouths), local in flavor, sordid, occasionally repulsive and crude, almost always obnoxious, solemn, and even monumental. His successors, however, are not to be found in Spain (today less than ever, God knows) but in England: Fielding and Sterne first and foremost, but also Dickens, Conan Doyle, and even Chesterton.

Sterne’s tremendous and very vocal admiration of Cervantes was such that at the threshold of death, just after he began a comical “romance” of which he left behind nothing but a brief sketch, Sterne expressed the following great hope, an open allusion to the author of Don Quixote:“When I am dead,” he said, “my name will be placed in the list of those heroes who died in a jest.”I doubt he could ever have imagined the way his wish would be fulfilled, for his posthumous jest continued to play its games long after he died, through the incredible travails that his dead body would be forced to endure.

Sterne lived in Coxwold, a tiny, placid village some twenty miles from York, and he would retreat to his lovely home there, Shandy Hall, to write in peace during the period in his life when his fame often lured him to London, or to travel through France and Italy for stretches of time. Nevertheless, he chose to meet his death at his very respectable lodgings in London, not Coxwold, so as not to cause his friends any unwarranted troubles or concern. As such, he was interred in London, at a burial ground in Hanover Square. Soon after his death, however, rumors began to circulate that his body had been purloined by grave robbers. A few days later, as a Cambridge University anatomy professor was enthusiastically dissecting a body, an audience member who had been recently introduced to Sterne removed the cover on the corpse’s stiff face and fainted on the spot, horrified by the discovery he had made. The professor, upon realizing the illustrious specimen that lay beneath his scalpel and saw, took pains to ensure that the body would be, at the very least, preserved and returned to its anxious grave. The whereabouts of Sterne’s skull, however, remained a mystery until some two hundred years later when, in 1969, the very distinguished and newly-minted Laurence Sterne Trust obtained permission to do some digging. After unearthing five skulls that were scattered about, they positively identified the one that had belonged to the creator of Tristram Shandy. It bore saw marks, which indicated it had passed through the hands of an anatomist, and its shape and dimensions matched perfectly with those of the lifesized bust that the sculptor Nollekens had created in Sterne’s likeness during the writer’s lifetime. Together at last, skull and bones were transferred to Coxwold, their true home, and buried anew at the Church of St. Michael’s, where Sterne had delivered so many jovial, ingenious, and eccentric sermons over the course of so many years, to the delight and shock of his parishioners.

This past summer, I visited that grave and also visited Shandy Hall, a charming house with a garden—ideal for writing—that the Laurence Sterne Trust acquired, restored, and reopened as a museum a few years back. In very Shandean style, a number of pensioners now hover about the house (one per room, to be exact), where they pounce upon the visitor, whether he likes it or not, and devote themselves to explaining all that can possibly be explained about the room in question. In the study, for example, I couldn’t possibly have imagined the writer himself sitting at his desk because his chair was occupied the entire time by the crusty old lecturer-of-the-moment who bubbled over with disquisitions and digressions. In the end though, disquisitions and digressions were Sterne’s trademark:“I progress as I digress,” he wrote.

I recently heard that someone is filming a movie based on Tristram Shandy, something I find truly surprising in our tell-all world that reveals all it can, as fast as it can and without wasting time, no doubt to summarily forget everything that has been revealed equally as fast. Shandy Hall, of course, belongs to another world—a cheerful, placid, timeless place that you can breathe and feel even today, so many years after he left it.

Translated from the Spanish by Kristina Cordero