Not long ago a friend and I went to the Prado to see the exhibit entitled “The Spanish Portrait.” As we walked through the show she turned to me at one point and asked, “Have you ever looked at a painting and felt intensely attracted to the subject for some reason? And then remembered that you will never meet the person, who has been dead for centuries. And yet, the person is still there, and you still feel attracted. What do you do when that happens?” My friend went on to confess that this had happened to her once while gazing at a reproduction of a portrait of the young Isaac Newton. Later on, we discussed this phenomenon with a friend of ours, who said that she had felt drawn in the very same way to a painting by Titian, of a young gentleman with long black hair and intense eyes, his face turned slightly to the side. I didn’t think I had much to add to the conversation; nothing of the sort had ever happened to me while looking at any painting, though I cannot deny having admired the elegant, icy beauty of Lady Helen Vincent, captured on canvas by John Singer Sargent around 1905. If memory serves me correctly, before she married, Lady Helen had been an actress, a woman used to being admired for her beauty, and so she allowed an art gallery to display Sargent’s painting in its window for all the world to see, a highly unusual occurrence in those days. After thinking about it a bit more, I realized something: on one or two occasions, while looking through newspapers and magazines, I had come across photographs of women I found so compelling that I cut them out and saved them, though I rarely ever looked at them again.

The first time it was a snapshot, most likely taken by the police, of a woman who looked vaguely Latin American, perhaps Colombian, and who had just been apprehended for some crime. I clipped the photo but not the corresponding news article—I suppose it was easier to admire her if I remained in the dark about her purported crimes. And then on another occasion—a few days ago, in fact—I found myself drawn to the photograph of a woman in an advertisement for one of those skin-care centers that are everywhere these days, the type that offer all sorts of gruesome treatments, including the surgical kind. I clipped the photograph, and for an instant, I couldn’t help but wonder if this woman—imperfect but extraordinary—had actually subjected herself to the procedures she promoted, and if the attraction I felt was the result of adulterations that I find horrible, precisely because they always seem to extinguish desire,and in general because such touch-ups are so incredibly and damningly obvious. But then I quickly remembered that in the world of advertising, one who endorses a given product is not necessarily a consumer of the product, and as such I was able to breathe a sigh of relief.

My level of fascination, however, is nothing compared to that of the Spanish writer Juan Benet, who on a trip to Italy noticed a promotional poster in one or two shoe stores for a certain brand of shoes. The photograph in question, if I remember correctly, exhibited a young woman caught in the act of buckling her shoe. The photographer had captured a long stretch of leg, but the woman’s features were partially hidden by her long hair. Benet found various things fascinating about this shot: the figure of the young woman, the difficult position she had been made to hold, and very possibly her foot. He was so drawn to this image that, after the third time he spotted it through the window of a shoe store, he walked inside and—I have no idea how—convinced the employees to sell him the poster. I have seen it on the wall at his country house at Zarzalejo, and Benet very proudly shows it to everyone who visits.

“All right, now,” he said to us.“What do you think? Was it worth it or not?”

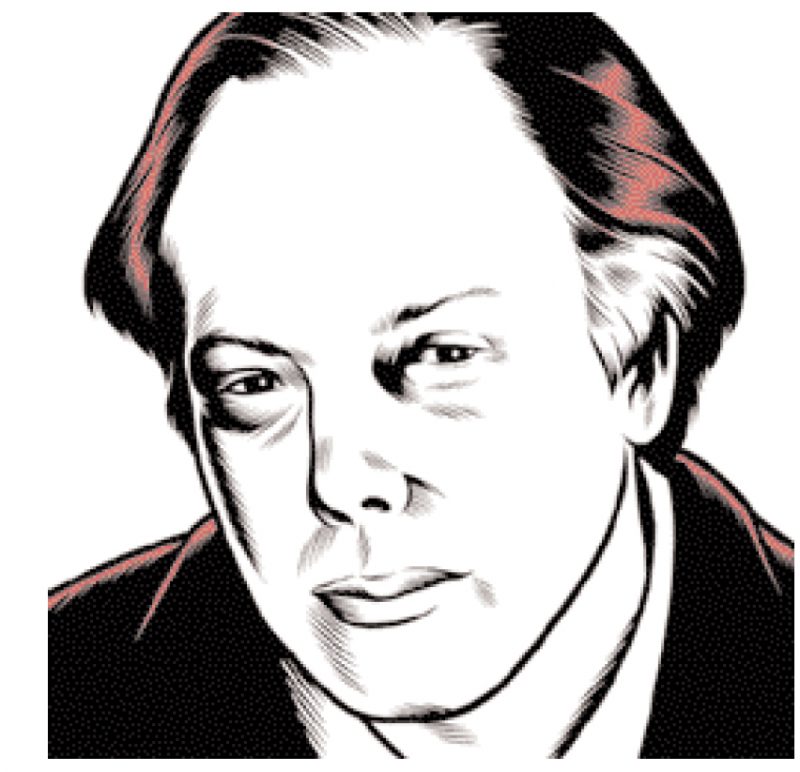

Something similar happened to another friend of mine: while flipping through a Sotheby’s catalogue I had received, she spotted a painting that had recently gone to auction. I hadn’t bid on it: It was the portrait of a young man (head and shoulders), with thick lips, a slightly haughty look in his eyes, and the long, flowing hair that was so fashionable during the age in which it was painted.The painter was cited as someone from “the circle of Nicholas de Largillière,” a French artist born in 1656 and who died in 1746, leaving behind more than a few paintings scattered throughout museums all over Europe. My friend’s fascination with this portrait, which was clearly more than just intellectual, was so intense that in anticipation of a very important event in her life, one which most definitely deserved an important gift, I contacted Sotheby’s to see if the painting was still available. Luckily it was, and after a bit of bargaining (the owner, it seemed, now wanted the painting back, but Sotheby’s had secured the right to sell it for a certain period of time following the auction), I bought it and gave it to my friend.And though the young man in the painting never ages, and my friend only grows older and older as time goes by, she still lives with him, and their relationship is far more harmonious than any she has maintained with her boyfriends or semi-boyfriends of recent years.

The question of things being “virtual” is nothing new, despite the copious images of sex that have suddenly become so readily available on every kind of screen imaginable. The virtual has always existed. The strange attraction we may feel for the subject of a portrait has been the sickly, obsessive domain of countless tales of terror throughout history. Outside the realm of literature, of course, we hope and pray that one day we will find ourselves gazing at a “double,” a person almost identical to the person who sat for the portrait we admire so. It isn’t as impossible as it may seem: at that very same exhibition my friend and I visited at the Prado, two familiar faces, those of Spain’s King Juan Carlos and Federico García Lorca, came together in one of the best portraits of the show, Goya’s The Family of Infante Don Luis. Look for the painting, and you will see that I know what I am talking about, and you also see that there is always reason to hope.

Translated from the Spanish by Kristina Cordero