1. THE OFFENDER

Nestled among the many mythic folds of American optimism, somewhere between equality of birth and it all coming out in the wash, lies the faith that everyone is perfectible, or at least redeemable, that there exists no sin so black that it cannot be scrubbed away with enough hard work and good old-fashioned penance. It’s the spiritual analogue of the Horatio Alger fable, cousin to our strangely persistent belief in our own openhearted inclusivity: the lion, if given half a chance, shall one day lie down with the lambs. No outcast, no murderer or thief wanders the roads and fields of our fifty states who cannot one day be brought back into the fold, dunked in the river, and made anew. There’s a place for everybody in America.

Everybody, that is, except Cary Verse.

Which is why he finds himself in a dingy seven-room runt of a motel in a section of San Jose apparently overlooked by the tech-boom renewal—just down the road from an aging drive-in, a gravel yard, a trailer court, and a transmission shop delightfully named “The Tranny Man.” Cary Verse arrived in San Jose on the fifteenth of March, six weeks after his release from Atascadero State Hospital, where he had been confined for six years after a Contra Costa County court declared him a Sexually Violent Predator, a legal category created by the California legislature in late 1995. He had passed the previous six years at San Quentin, Corcoran, and New Folsom state prisons, serving time for three felony counts of sexual assault after beating, tying up, and nearly raping a man he had met in a Richmond homeless shelter. He never killed anyone, or even came close, but while murderers are often paroled without a murmur, outcry has dogged Verse at every step.

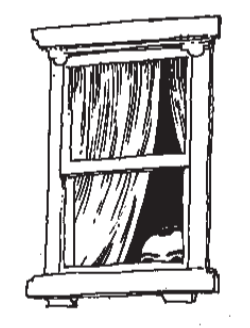

Sitting at the head of the bed in his beige-walled motel room, Verse expects he will have to pack up the few belongings scattered on the TV cabinet and the bedside table—a portable DVD player, a tape recorder, a Rubik’s cube, stuffed animals, clothes, toiletries, a few inspirational books—and leave within a week. “Pretty quick,” he observes with a laugh.

It is hard to avoid the term “mild-mannered” in describing Cary Verse. He is thirty-three, with light reddish-brown skin, sleepy eyes, and a small mustache. He is a tall man, but his body language is self-effacing and his smile warm enough. There is nothing immediately off about him, except perhaps a certain flatness to the rhythms of his voice, which may be the fault of Depakote, which he takes for bipolar disorder (a diagnosis he once actively disputed but now resignedly accepts, though he still has his...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in