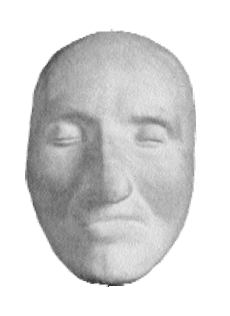

Thomas Paine keeps staring at me from this old book, his nose bent to one side like an aged boxer’s. He’s had a tough life and an even tougher afterlife. I’ve spent the last few years pursuing his bones: they were stolen in 1819, and since then have reappeared everywhere from a New York sewage ditch to a Paris hotel room, with occasional stopovers inside statues and pieces of furniture. As I pursued the skull and bones of Paine, perhaps it was only a matter of time before I crossed paths with this book by Laurence Hutton, the man who once possessed Paine’s face… not to mention Franklin’s, Lincoln’s, and Aaron Burr’s faces too.

When Hutton is remembered today, it’s as Mark Twain’s editor at Harper & Brothers. But it was his obsessive pursuit of plaster death masks that once caught the public’s attention; Hutton could confidently lay claim to having “the most nearly complete and the largest collection of its kind in the world.” Like many Victorian memento mori, his resulting 1894 opus Portraits in Plaster is an object of unnervingly beautiful craftsmanship: its thick and creamy paper bears scores of photographs of the immortal yet all too-mortal. Here are Keats and Coleridge; there are Swift and Johnson. Twain’s editor had gazed into the face of Whitman and had cradled the molded cheeks of Grant and Sherman, the latter pair vanquished at last by a truly implacable foe.

The actor David Garrick, looking for all the world like a fifth Baldwin brother, proved to be an unusual life mask acquisition. Though life and death masks alike enjoyed a vogue in the nineteenth century, bolstered in no small part by the popularity of phrenology, Hutton’s distinct preference for death masks was actually rather humane of him. “The procedure of taking a mould of the living face is not pleasant to the subject,” he noted. “In order to prevent the adhesion of the plaster, a strong lather of soap and water, or more frequently a small quantity of oil, is applied to the hair and to the beard…. quills are inserted into the nostrils in order that the victim may breathe during the operation, or else openings are left in the plaster for that purpose.” The subject—be he a pope, poet laureate, or president—was then unceremoniously made to lay his head back in a big pan of wet plaster, whereupon the artist proceeded to smear the glop over him. Then he had an agonizingly motionless wait as the stuff hardened. Death masks are different, though; the only discomfort involved is that of the onlookers. A death mask is the visage of a man whose guard is down—forever.

“He does not pose; he does not ‘try to look pleasant.’” Hutton explained of his compliant subjects. “In his mask he is seen, as it were, with his mask off!”

Hutton’s great collection began in earnest with an unlikely coincidence. He had been lingering in the Broadway storefront of the phrenologists Fowler & Wells when a young boy came in bearing a plaster mask; he’d found it in a trash can and didn’t know what it was, but he’d guessed that a store dedicated to head exams might want it. The face proved to be that of Oliver Cromwell, and not an artist’s rendition nor a mere plaster plaque, but an impression made from Cromwell’s own skin and bones as he lay lifeless on his deathbed. There are more, the boy told Hutton. They set out towards the East River to find a precious heap of trash at the corner of 2nd St. and 2nd Ave., where more faces emerged into daylight: Sir Walter Scott, Laurence Sterne, Wordsworth, even Ben Franklin. “Their owner had lately died.” Hutton wrote in 1894 of the cache he discovered that fateful day. “His unsympathetic and unappreciative heirs had thrown away what they considered ‘the horrible things.’”

Hutton haunted curio shops to find more, even tracking down their original makers; he presented an alleged Aaron Burr mask to the very man who had poured the plaster over Burr’s dead face in 1836. It was, the sculptor assured him, the same mask, having miraculously survived decades of neglect. Other faces were not so fortunate: after scouring junk shops in Europe, Hutton sometimes found his discoveries could not survive the trip home. His joy in the mask of Elihu Burritt—“the learned blacksmith” and social crusader who taught himself foreign languages while hammering at the anvil, until he had mastered fifty tongues—was dashed when the smith’s face proved rather less durable than the iron it had once sweated over. The ghastly relic made it all the way across the ocean only to get shattered to pieces inside the New York Customs House. With his visage gone, it was as if Burritt had died twice.

*

Hutton was always chasing a past that could only be held in proxy, in its plaster shell with the living substance beneath irrevocably lost. Throughout the 1880s and ’90s he released a series of seven painstakingly researched guides—Literary Landmarks of London first, and then six more volumes on the literary landmarks of Rome, Florence, Venice, Jerusalem, Oxford, and Edinburgh. They are fascinating books: each tries tracking down where local writers once ate, slept, worked, drank, or worked while drinking. What Hutton found in London was that, along with the historian’s bane of streets getting renumbered, the homes of his beloved authors were already getting demolished. A few buildings were left as he wrote: war and the intervening century have probably taken care of most of those. His Literary Landmarks books are, if you will, the death masks of entire cities—portraits in brick and plaster. It is only when you realize this that Portraits in Plaster no longer looks like some wild undergrowth among his Literary Landmarks: it is, in fact, the blossom upon their stem.

Though rare, there are other such flowers in the field. The titles in the death mask genre might be counted on your fingers, and most notably include Ernst Benkard’s haunting 1926 study Das Ewige Antlitz, a volume that so intrigued Leonard and Virginia Woolf that they had it translated and published three years later under the English title Undying Faces. The one truly undying face in the book was also the most anonymous one: a death mask known as the Inconnue de la Seine, molded from a unidentified young woman who drowned herself in Paris at the turn of the century. There was a near-cult of the Inconnue among French and German art students in the 1920s and ’30s; replicas of her faintly smiling mask hung on their walls as a spooky aesthetic ideal. And she hasn’t gone away: in a fine bit of turnabout, the Inconnue’s mask became the face of “CPR Annie,” the first-aid training mannequin familiar to anyone who ever took a Red Cross or a high school health class.

Both Hutton’s and Benkard’s books are rare finds today. What has become more common is the book that, rather than preserving the eyeless plaster gaze of the dead, instead follows the remains under that mask. There is no word for such books, though they are indeed a distinct genre unto themselves: let us call them necrologues, shall we? They are the joyously black-humored offspring of disreputable old disinterment pamphlets, making their ancestry nearly as old as that of the novel itself. If you seek a rapscallion grandfather for the genre, you might as well pick up Philip Neve’s 1790 account A Narrative of the Disinterment of Milton’s Coffin in the Parish Church of St. Giles, Cripplegate, which recounts—in a way that is appalling, funny, and thus appallingly funny—how drunk sextons digging up the poet’s grave for a new monument quickly turned the job into a wild sideshow, complete with a cover charge for beer at the Cripplegate entrance. The old Puritan poet was set upon by local curiosity-seekers who indeed sought and found his fingers, toes, ribs, teeth, and… in short, reader, they stripped him like a Jersey chop-shop.

Other disinterment writers followed. The eccentric Victorian naturalist Frank Buckland oversaw the rather straightforward exhumation of playwright and Shakespearean drinking buddy Ben Jonson, helped in his work by a pair of gravediggers improbably named “Spice” and “Ovens.” A later mission to find and memorialize the famed surgeon John Hunter was not so easy, though. Buckland’s Curiosities of Natural History (Fourth Series, 1872) recounts how he spent eight days rooting through Vault 3 of the Church of St. Martin’s-in-the-Fields, among coffins piled and scattered madly about like so many toys, moving more than 3,000 of them before reaching the top coffin of one fateful pile: “As it moved off, I discerned first the letter J, then the O, and at last the whole word JOHN.” Gases had caused Hunter’s lead coffin to burst—a ghastly touch its occupant would have appreciated, as Dr. Hunter was once the country’s most zealous pursuer of cadavers. A modern-day Buckland and Hunter might also add to their bookshelf not one but two pamphlets tracing Thomas Paine’s bones, and Canon Thomas Barber’s odd 1939 book Byron and Where He Is Buried. (The short answer: in Byron’s tomb.) The clergyman, proceeding with the familial approval of Lord Byron of Thrumpton Hall, not only made a midnight visit to the final resting place of the ancestral poet—this to end rumors that the body was missing—he also drew up for readers a foldout diagram of the Byron family vault. That, I suppose, is just in case you want to try digging him up, too.

These days our tastes run more to travel writing that proceeds horizontally than vertically: and so, too, the necrologue. We road-trip across the country with a physicist’s brain in Michael Paterniti’s Driving Mr. Albert (2000), and discover in Russell Martin’s Beethoven’s Hair (2000) how a fifteen-year-old protégé snipped off a lock of the dead composer, the snippet traveling with Jewish refugees through Denmark—one of whom later wound up acting in Woody Allen’s Take the Money and Run—and eventually landing on the table of an Arizona urologist. Most recently, Sergio Luzzatto’s study Il Corpo Del Duce was translated and released in 2005 as The Body of Il Duce. Luzzato follows Mussolini’s body from its roadside execution to the Milan plaza where it was hung upside down at a gas station, and pelted and pissed on by a jeering mob; and from there resurrected from his unmarked grave on Easter Day 1946 by Fascist admirers. Il Duce thereupon spends eleven ignominious years in a wooden footlocker hidden by Franciscan friars before finally being deposited in a family crypt: home at last, if home is a place where neo-Fascist admirers pray and disenchanted former followers deride you as “Great Chief Asshole.” Luzzatto’s study is not even the first upon the subject: that distinction goes to the fascist graverobber Domenico Leccisi, who proudly penned the 1948 memoir I Stole Mussolini’s Body. Eventually both Mussolini’s Socialist executioner and Fascist resurrectionist were elected to the Italian parliament—men united in nothing save having handled the same deceased dictator.

But it is their stories that Luzzatto’s book and all necrologues revolve around. Dead bodies make for difficult protagonists: just ask the scriptwriter for Weekend at Bernie’s. A dead body doesn’t do anything, and—unless you’re insane—it doesn’t say anything, either. So a necrologue is of necessity not about that person… because he is not a person at all… because he is dead. The body at the center of a necrologue is what Alfred Hitchcock used to call a macguffin. Like the roll of microfilm in a spy thriller, it is an object with no real meaning except that it sets everything around it in motion.

A necrologue is all about the living: the story of the dead is already over.

*

Yet we cling to their objects, to the impress of their faces upon the world. How can we not? And for all the palpable loss Hutton’s masks represented, they still can be found. Though few know of the masks’ existence, late in life Hutton donated them to Princeton University, where the Hutton Collection can now be found on the library website. The library is planning an exhibition; Keats and Whitman and Disraeli will all gaze upon the world once again, but with their eloquent mouths now muted. Until then, the masks are ensconced in archival drawers, staring into appropriately cryptal darkness.

Hutton himself spent his final years well away from the masks, and instead took a long South Pacific cruise with Mark Twain. Perhaps Hutton sneaked the occasional appraising glance at his shipmate’s head; after all, he didn’t hesitate to collect masks of his own friends and acquaintances, though even he could be a little spooked by this practice. “I can only look upon the casts of the dead faces as I looked upon their dead faces themselves a few months ago,” he admitted, “and grieve afresh for what I have lost.”

But one death mask that he never did get was of this most famous friend of all: Twain is conspicuously absent from Hutton’s book and his collection. There are some obstacles that even the most intrepid collector cannot surmount. For it was Laurence Hutton, you see, who died first.