“I wish I had a better story for you,” confides the unnamed narrator a third of the way into Jane Unrue’s new miniaturist novel, though there’s hardly cause for so modest a claim. With just over one hundred pages, some of them hosting no more than a wee phrase or the clarion burst of a sentence, and most of them giving out well shy of the bottom margins, the novel, though slender, is emotionally thorough, dense but not crammed, and unnoisily original in the bloodbeat and quiver of its prose.

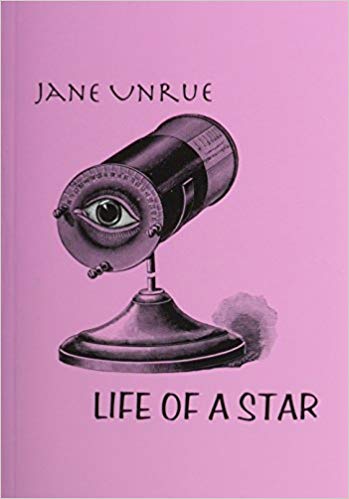

Unrue writes intricate, ribbony sentences that often reel themselves into the safeholds of eccentrically stacked, unindented paragraphs as lyrically loaded as Joseph Cornell boxes. Sometimes these gracile ribbons get snipped short of tidying grammatical resolution; the narrator, we learn, is in fact something of a mean whiz with a scissors and a knife.

Nearing (or already well submerged in) the loneliness and lovelessness of early middle age, she’s the daughter of a washed-up actress, and though not officially an actress herself, she has discovered the only certain way to insert herself acutely into experience: to regard every instant as an opportunity for performance, for representing herself rather than entirely being herself (and whatever further self-discovery that might finally require). So confused is her life with theatricality that rain falls “as if it had been yanked from buckets poised on rafters up above,” and stage directions are tucked into her thoughts, slipcased between parentheses—“(Full-body modesty)”; “(Mild eyebrow tip)”; “(single-handed heart-grip).” “Since there is artificiality in mere utterance,” she’s convinced she “must live the words.”

But life, as she practices the living of it, amounts to casting herself into an ever-narrowing repertoire of melancholy enactments unfolding mostly in the galleries of a museum (through which, profusely ruffled and garbed in preposterous layerings of underskirts and other costumic outlandishments, she kills hour after hour skulking coquettishly, hoping to pry one or another man loose from an alarmed wife) and by the fountain in a public garden, where she suffers little more than half a dozen rendezvous with, one gathers, her only lover ever, a worldly man who is apparently married (it’s a furtive, futureless courtship). From these outings she returns, unconsoled, to the ticktock isolations of her rented room, where she spinsterishly busies herself with embroidering a bumblebee onto a pillowcase (her goal, fittingly enough, to arrest the buzzy wingbeats into a stitchy stillness) and broods...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in