- Contains: Rhomb of Iceland Spar

- Listed by: the Queen and Co. Catalogue of Philadelphia, 1888

- Intensity: High

- Burn time: perhaps a minute or more

THE PARLOR TRICK

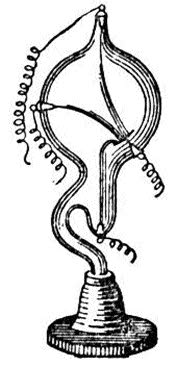

Heinrich Geissler’s whimsically shaped lightbulbs—with their twists and coils, their tuberous cul-de-sacs—connote otherworldly botanical species. They also recall primitive medical instruments, crude gynecological scopes and human plumbing snakes. Yet Geissler was an inventor of and for enjoyment; his evacuated glass vessels were produced for parlor tricks and post-dinner entertainment. (This 1857 technology would later be used to develop X-rays, incandescent lamps, neon lights, television.) So, imagine: the parlor lamps extinguished. The coffee cups rattled back into their saucers. The rustle of too many clothes against too many other clothes on the divan. The hiss, the hum, the snap as the metal electrodes sizzle to action. These visible cathode rays bounce off items captured in the glass that produce a bewitching phosphorescence—a rhomb of Iceland spar, for example, gives off a yellow light—a show that lasts hardly a minute. This is lightning so small you can hold it in your hand.

BRIEF BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Heinrich Geissler (1814 to 1879) was born in the village of Igelshieb, now a suburb of Neuhaus am Rennweg, Germany. His father, George, was an innovative glassblower. Heinrich earned his living as a traveling instrument maker before setting up a workshop in Bonn, where he collaborated with physicists, medical doctors, and mineralogists to make his “beautiful electric toys.”

ONE MILLIONTH OF AN ATMOSPHERE

Geissler Tubes are also known as Crookes Tubes. Sir William Crookes’ innovative improvements to Geissler’s mercury vacuum pump system produced vacuums exceeding one millionth of an atmosphere—is this a thing? Is it smaller than an ant’s fingernail? Tinier than the pupil on the eye of a paramecium?—which made possible the discovery of X-rays, the electron, and nuclear and particle physics. Crookes’ austere Maltese Cross Tube resembles a transparent Hindenberg with a Third Reich-inspired metal electrode heart. This is war in a bottle.

BRIEF BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Sir William Crookes (1832 to 1919), born in London, was the son of a tailor. In a letter, Crookes declines a dinner invitation because of a previous engagement at a séance. It is not known whether or not he was taking electrical equipment to the séance, but one scholar surmises that he planned to perform experiments on the dead.

THE PARLOR TRICK II

Could Crookes have predicted that Wilhelm Roentgen would use his technology to discover the X-ray, and that Roentgen would take the first official “roentgenogram” of his wife’s hand, immobilized on a photographic plate and upon which slowly (very slowly—the first X-rays took three hours) there appeared a fencing of bones and knuckles, her wedding ring, surrounded by a nimbus of flesh and muscle? And Heinrich Geissler—could he ever, in his most fantastically loopy imaginings, have conjured the image of Las Vegas, where the neon offspring of his invention thrived in a weedy tangle bigger than the sky? Could he or Crookes have conceived of the replacement of parlor tricks by the tireless hum of the Tube? Could they have envisioned a world where we watch this hypnotic apparatus for news of their other errant progeny, nuclear warheads? What wishful thinking that we might still delight in destruction inside a glass tube—quick-burning, beautiful, contained.