I. AMONG THE JOURNALIST ANTS

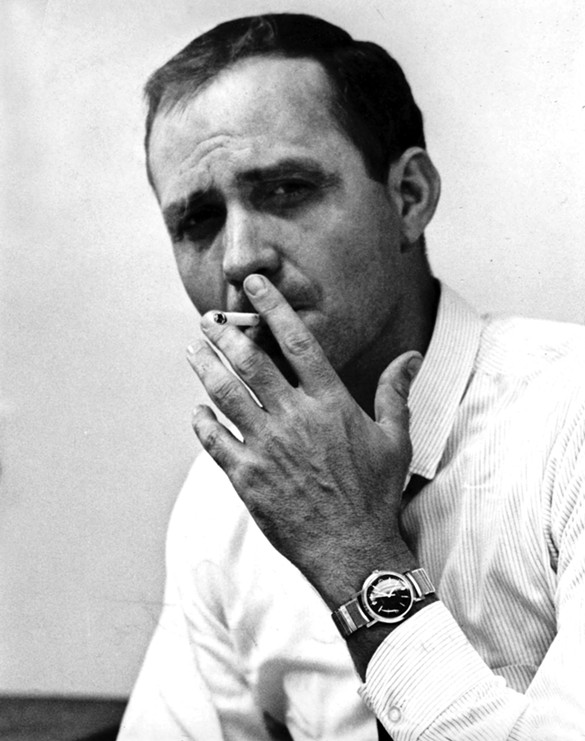

In 1964, in the midst of so-called Swinging London, Charles McColl Portis had Karl Marx’s old job. Portis (who turns seventy this year) was thirty at the time, not yet a novelist, just a newspaperman seemingly blessed by that guild’s gods. His situational Marxism would have been hard to predict. Delivered into this world by the “ominous Dr. Slaughter” in El Dorado, Arkansas, in 1933, Charles Portis—sometimes “Charlie” or “Buddy”—had grown up in towns along the Arkla border, enlisted in the Marines after high school and fought in the Korean War. Upon his discharge in 1955, he majored in journalism at the University of Arkansas (imagining it might be “fun and not very hard, something like barber college”), and after graduation worked at the appealingly named Memphis Commercial Appeal. He soon returned to his native state, writing for the Arkansas Gazette in Little Rock.

He left for New York in 1960, and became a general assignment reporter at the now defunct New York Herald-Tribune, working out of what has to be one of the more formidable newsroom incubators in history—his comrades included Tom Wolfe (who would later dub him the “original laconic cutup”) and future Harper’s editor Lewis Lapham. Norwood’s titular ex-Marine, after a fruitless few days in Gotham, saw it as “the hateful town,” and Portis himself had once suggested (in response to an aspersion against Arkansas in the pages of Time), that Manhattan be buried in turnip greens; still, he stayed for three years. He apparently thrived, for he was tapped as the Trib’s London bureau chief and reporter—the latter post held in the 1850s by the author of The Communist Manifesto (1848). (More specifically, his predecessor had been a London correspondent for the pre-merger New York Herald.) Recently, in a rare interview for the Gazette Project at the University of Arkansas, Portis recalls telling his boss that the paper “might have saved us all a lot of grief if it had only paid Marx a little better.” [1]

Indeed, as Portis notes in his second novel, the bestselling True Grit (1968), “You will sometimes let money interfere with your notions of what is right.” If Marx had decided to loosen up, Portis wouldn’t have gone to Korea, to serve in that first war waged over communism, and (in the relentless logic of these things) wouldn’t have put together his first protagonist, taciturn Korea vet Norwood Pratt, in quite the same way. Perhaps the well would have run dry—fast. Instead of writing five remarkable, deeply entertaining novels (three of them surely masterpieces, though which three is up for debate), Portis could be in England still, grinding out copy by the column inch, saying “cheers” when replacing the phone.

In any event, Portis left not only England but ink-stained wretchdom itself—“quit cold,” as Wolfe writes in “The Birth of the New Journalism: An Eyewitness Report” (1972), later the introduction to the 1973 anthology The New Journalism. After sailing back to the States on “one of the Mauretania’s last runs,” he reportedly holed up in his version of Proust’s cork-lined study—a fishing shack back in Arkansas—to try his hand at fiction.

These journalists work pretty fast, and the slim picaresque Norwood appeared in 1966, to favorable notice. Portis’s signature drollery and itinerant protagonist (Norwood Pratt, auto mechanic and aspiring country singer, ranges from Ralph, Texas, to New York City and back, initially to recover seventy dollars loaned to a service buddy) are already in place. The supporting cast includes a midget, a loaf-groping bread deliveryman and a sapient chicken, and a looser hand might have plunged the tale into mere chaos or grotesquerie. But Portis’s sense of proportion is flawless, and the resulting panorama, clocking in at under 200 pages, stays snapshot-sharp throughout—a road novel as indispensible as On the Road itself.[2]

With reportorial precision, and without condescension, Norwood captures all manner of reflex babble, the extravagant grammar of commercial appeal—stray words bathed in the exhaust of a Trailways bus. This omnivorous little book has a high metabolism, digesting everything from homemade store signs (“I Do Not Loan Tools”) and military-base graffiti to actuarial come-ons and mail-order ads for discount diamonds. Appropriately enough, the characters are constantly chowing down. On one leg of the journey, Edmund B. Ratner (formerly the “world’s smallest perfect man,” before he porked out) and Norwood’s new sweetheart, Rita Lee Chipman, are described as having eaten their way through the Great Smoky Mountains. Norwood’s decidedly humble (call it American) menu nails the country’s midcentury gastronomy with a precision that today takes on near archaeological value: canned peaches, marshmallows, Vienna sausages, cottage cheese with salt and pepper, a barbecue sandwich washed down with NuGrape, a potted meat sandwich with mustard, butter on ham sandwiches, biscuit and Br’er Rabbit Syrup sandwiches, an Automat hot dog on a dish of baked beans, Cokes and corn chips and Nabs crackers, a Clark bar, peanuts fizzing in Pepsi, a frozen Milky Way.

*

No bloat for Portis, and no sophomore slump, either: In 1968 The Saturday Evening Post serialized True Grit, a western that both satisfies and subverts the genre. (The only title of his to have remained almost continuously in print, True Grit has just been republished by Overlook, joining that press’s recent paperback reissues of the author’s four other books.) The novel, published later that year by Simon & Schuster, could hardly seem more out of step with the countercultural spirit of ’68.[3] Writing in 1928 (i.e., on the eve of the Great Depression), a spinster banker named Mattie Ross revisits the central chapter in her life: the winter of 1873, when, as a fourteen-year-old from Yell County, Arkansas, she hunted down her father’s killer, Tom Chaney, with the help of a tough U.S. marshal that she hires (the “old one-eyed jasper” Rooster Cogurn) and a young Texas Ranger (the cowlicked LaBoeuf).

“Thank God for the Harrison Narcotics Law,” Mattie declares, in what might have read as a sort of antediluvian rebuke to the era of one-pill-makes-you-listen-to-Jefferson-Airplane. “Also the Volstead Act.” Mattie never minces words or judgments—she’s not from Yell County for nothing—and the poles of wrong and right are firmly fixed. Unlike Huck Finn, to whose narrative hers is sometimes compared, Mattie knows the Bible back to front, handily settling spiritual debates by citing chapter and verse. To those men of the cloth, for example, who might conceivably take issue with her belief that there’s something sinister about swine, she says: “Preacher, go to your Bible and read Luke 8: 26–33.”[4] (Portis’s father was a Scripture-studying schoolteacher, and his mother—whose name he gives to the steamer Alice Waddell—was the daughter of a Methodist minister.) Her steadfast, unsentimental voice—Portis’s sublime ventriloquism—maintains such purity of purpose that the prose seems engraved rather than merely writ.

When Roy Blount, Jr., says that Portis “could be Cormac McCarthy if he wanted to, but he’d rather be funny,” he may be both remembering and forgetting True Grit, which for all its high spirits is organized along a blood meridian, fraught with ominous slaughter. Blood literally stains the book’s first and last sentences, and Rooster, though admirable in his tenacity and his paternal protectiveness of Mattie, has a half-hidden history of trigger-happy law enforcement and less defensible acts of carnage. Indeed, the Overlook reprint provides a necessary corrective for latter-day Portis enthusiasts, a prism for the acts of violence in his other books: the cathartic fistfight punctuating Norwood’s homecoming and Gringos’ startlingly gory if swift climax. (The latter novel’s narrator, Jimmy Burns, is also a Korean War vet, and Norwood reveals to Rita Lee that he killed two men “that I know of” in that conflict.) Portis’s current reputation as a keen comedian of human quirks, though well-deserved, is limiting. Put another way: After cars, Portis is most familiar with the classification and care of guns. (Even Ray Midge, the ever-observant milquetoast who tells his story in 1979’s The Dog of the South, knows his firearms.)

Not that True Grit stints on comedy—in one of the funniest set pieces to be found in all of Portisland, Rooster, LaBoeuf, and a Choctaw policeman suddenly break into an escalating marksmanship contest, pitching corn dodgers two at a time and trying to hit both, eventually depleting a third of their rations. Mattie’s precocious capacity for hard-bargain-driving (selling back ponies to the beleaguered livestock trader Stonehill) is revealed in expertly structured repartee, and her rock-ribbed responses to distasteful situations amuse with their catechism cadences. (When Rooster, in his cups, offers sick Mattie a spoonful of booze, she intones, “I would not put a thief in my mouth to steal my brains”). But Mattie also re-creates, poignantly and despite herself, her stark discovery of a world gone suddenly wrong, and what had to be done to set it right. Old Testament resonances are always close at hand: Her father’s killer bears a powder mark on his face, a Cain figure to say the least, and not to be pitied, and her own taste for frontier justice will lead her into a pit of terror, biblically populated by snakes. The price that Mattie pays may be greater than she knows.

True Grit’s fame, of course, extends well beyond the book itself. The phrase has lodged in the culture, somewhere below catch-22 and above nymphet. And Henry Hathaway’s enjoyable if foreshortened film version (1969) firmly yokes the story to John Wayne, who at sixty-two won his only Oscar for his portrayal of Rooster. Alas, the movie (which also stars Kim Darby as Mattie and Glen Campbell as LaBoeuf) doesn’t capture the retrospective quality of Mattie’s voice, as she fixes on the events over the widening gulf of years (“Time just gets away from us,” she writes, in the book’s penultimate and heartbreaking line). Wayne, in a full-bodied performance, draws the focus away from his employer/charge, so that the title refers far more to Rooster than Mattie.[5]

Some see the book as Portis’s albatross. Ron Rosenbaum, whose enthusiasm for the novelist’s lesser-known works was instrumental in their republication, found it necessary (in a 1998 Esquire piece) to distance Portis from his most famous creation (“too popular for its own good”), in order to make his case for the true gems of the Portis canon. But the novel occupies a position similar to that of Lolita in relation to Nabokov’s works: Though it might not be your personal favorite, it cannot be subtracted from the oeuvre; nor can his other writings fall outside its shadow.[6] If Portis’s subsequent novels—The Dog of the South, Masters of Atlantis, Gringos—have as a shared theme the seriocomic echo of lost, irretrievable greatness,[7] it’s possible that True Grit is the genuine article—a book so strong that it reads as myth. As Wolfe notes of Portis’s enviable success: “He made a fortune… A fishing shack! In Arkansas! It was too goddamned perfect to be true, and yet there it was.” And here it is—here it is, again.

*

In The New Journalism, Wolfe invokes the original laconic cutup, who happened to sit one desk behind him at the Trib office south of Times Square, as stubborn proof that the dream of the Novel—with its fortune-changing, culture-denting potential—never really died, even at a time when journalists were discovering new narrative ranges, fiction-trumping special effects. There was only one trophy worth typing for, one white whale worth the by-line and fishing wire, the Great, or even just the Pretty Good, American Novel, and Charlie Portis was going to try and snag it.

Or maybe the scoopmonger’s life just bugged him. In “Your Action Line,” a two-page lark published in The New Yorker at the end of 1977 (still in the eleven-year no-novel zone between True Grit and The Dog of the South), Portis addressed such pressing queries as “Can you put me in touch with a Japanese napkin-folding club?” (If a similar peep had emerged from Camp Salinger, it would scan as Zen koan.) The exchange ends with encyclopedia-caliber dope on a heretofore obscure insect:

Q—My science teacher told me to write a paper on the “detective ants” of Ceylon, and I can’t find anything about these ants. Don’t tell me to go to the library, because I’ve already been there.

A—There are no ants in Ceylon. Your teacher may be thinking of the “journalist ants” of central Burma. These bright-red insects grow to a maximum length of one-quarter inch, and they are tireless workers, scurrying about on the forest floor and gathering tiny facts, which they store in their abdominal sacs. When the sacs are filled, they coat these facts with a kind of nacreous glaze and exchange them for bits of yellow wax manufactured by the smaller and slower “wax ants.” The journalist ants burrow extensive tunnels and galleries beneath Burmese villages, and the villagers, reclining at night on their straw mats, can often hear a steady hum from the earth. This hum is believed to be the ants sifting fine particles of information with their feelers in the dark. Diminutive grunts can sometimes be heard, too, but these are thought to come not from the journalist ants but from their albino slaves, the “butting dwarf ants,” who spend their entire lives tamping wax into tiny storage chambers with their heads.

If Portis had long since escaped the formicary, his books nevertheless continued to draw on his previous work environment. Here and there, fixed in amber, his former fellow ants appear.

Heading the London bureau, Portis kept getting entangled in “management comedies,” expending too much precious time trying to stamp out unscrupulous freeloaders; he describes (for the Gazette Project) setting up a small sting operation to nab a writer who was using a tenuous Trib association—a single review, written years prior—to score theater tickets gratis. But Portis’s fictional portraits of the less-upstanding members of the trade are not without a certain affection. The rogues are legion: Norwood breaks bread in Manhattan with Heineman, a freelance travel writer (supposedly on deadline for a Trib piece) who writes articles on Peru from his Eleventh Street digs and frankly aspires to the freeloading condition. (Laziness, he confesses, holds him back.) In Masters of Atlantis, hack extraordinaire Dub Polton, commissioned to compose the biography of Gnomon Society head Lamar Jimmerson, has a formidable reputation (“He wrote So This Is Omaha! in a single afternoon,” says one awed Gnomon), and is so confident in his vision for Hoosier Wizard that he doesn’t take down a single note. The master of this subspecies of charlatan might be overweening travel writer Chick Jardine. In Portis’s jaunty 1992 story for The Atlantic, “Nights Can Turn Cold in Viborra,” the consummate insider confesses to his readers, “I seldom reveal my identity to ordinary people,” while taking pains to mention his “trademark turquoise jacket”—perhaps a gentle dig at the dapper Wolfe. Chick has also devised a product called the Adjective Wheel, which he sells to his fellow (well, lesser) travel writers at $24.95 a pop.[8]

More abusive than even writers, of course, are editors. In the Gazette Project interview, Portis mentions a job in college for a regional paper, where he edited the country correspondence:

…from these lady stringers in Goshen and Elkins, those places. I had to type it up. They wrote with hard-lead pencils on tablet paper or notebook paper, but their handwriting was good and clear. Much better than mine. Their writing, too, for that matter. From those who weren’t self-conscious about it. Those who hadn’t taken some writing course. My job was to edit out all the life and charm from these homely reports. Some fine old country expression, or a nice turn of phrase—out they went.

Perhaps as penance for these early deletions, he created Mattie Ross, whose idiosyncratic style is most immediately identifiable by her liberal, seemingly arbitrary use of “quotation marks”—as if to let a phrase “stand alone” was to risk having it “fall by the wayside” at the whim of some “blue pencil.” (A brief list of Mattie’s punctuated preferences would include “Lone Star State,” “scrap,” “that good part,” “moonshiners,” “dopeheads,” “Wild West,” “land of Nod,” “pickle,” and “night hoss.”) The punctuation not only highlights the phrases in question—some of them perhaps “old country expressions” of the time—but also comes to reflect her thriftiness. If True Grit is Mattie’s true account, meant for publication, then the quote marks act as preservatives—insurance that her hard work will not be weeded out by some editorial know-it-all. Quotation marks mean the thing is true—to the degree that someone said it, or that it had some currency then.[9]

For Mattie has, apparently, tried her hand at the freelance game. An earlier experience with the magazine world came to grief. She has written a “good historical article,” based mostly on her firsthand observation of a Fort Smith trial, prior to meeting Rooster Cogburn. Though the piece has a rather vivid (or as she would say, “graphic”) title—“You will now listen to the sentence of the law, Odus Wharton, which is that you be hanged by the neck until you are dead, dead dead! May God, whose laws you have broken and before whose dread tribunal you must appear, have mercy upon your soul. Being a personal recollection of Isaac C. Parker, the famous Border Judge”—the magazine world “would rather print trash.”

As for newspapers, the cheapskate editors “are great ones for reaping where they do not sow”—always hoping to short-change contributors, or else sending reporters around to get an interview gratis. Ever the banker, Mattie means for her story to make money—which True Grit went ahead and did.

*

Totting up his fee sheets, a struggling Rooster opines that unschooled men like himself have a raw deal. “No matter if he has got sand in his craw, others will push him aside, little thin fellows that have won spelling bees back home.” A century hence, this orthographical ace might be Raymond E. Midge, the twenty-six-year-old ex–copy editor and perpetual college student who narrates The Dog of the South (1979). That Portis effortlessly makes Midge, a nitpicking, book-burrowing cuckold, as indelible and appealing as the battle-scarred man of action (or strong-willed girl revenger) is ample proof of his scope and skill.

Thanks to a few wizards of international fiction, the proofreader has had some pivotal roles—Hugh Person in Nabokov’s Transparent Things (1972), Raimundo Silva in Jose Saramago’s The History of the Siege of Lisbon (1996). Denizens of the copy desk have not enjoyed a similar literary profile. Though the professions bear some resemblance, the latter’s task is more Sisyphean and perhaps more conducive to despair—sweating the details on something as disposable as a newspaper, in most cases gone inside a week, if not a day. No novel captures the occupation’s particular brand of virtues and neuroses as well as The Dog of the South; it’s the perfect job (or former job) for a character so constitutionally driven to remark on deviations from the norm. (At twenty-six, he’s lived as many years as there are letters in the alphabet.) Ray Midge sets out for British Honduras to recover his car and perhaps Norma, his wife[10]—both stolen by his former co-worker, the misanthropic Guy Dupree. Dupree’s errant behavior—he’s finally investigated for writing hostile letters to the president—and burgeoning anarcho-communist tendencies reflect a harsh if hysterical world view possibly aggravated by his days in the newspaper office: “He hardly spoke at all except to mutter ‘Crap’ or ‘What crap’ as he processed news matter, affecting a contempt for all events on earth and for the written accounts of those events.”[11]

Midge, conversely, pays enormous attention to all events on earth, and The Dog of the South, his written account of them, allows the reader to share his pleasure. “In South Texas I saw three interesting things,” he writes, and then lists them. Indeed, he’s inordinately proud of his better-than-average vision, noting that he can “see stars down to the seventh magnitude.” Perhaps it is something to boast about, but in compensation for his assorted failings, he seems to have attributed to his eyesight super-hypnotic powers:

I watched the windows for Norma, for flitting shadows. I was always good at catching roach movement or mouse movement from the corner of my eye. Small or large, any object in my presence had only to change its position slightly, by no more than a centimeter, and my head would snap about and the thing would be instantly trapped by my gaze.

*

A military history buff with “sixty-six lineal feet” of books on the topic (he would know the exact dimensions), Midge sees himself on a mission, and in his hilarious, unconscious self-inflation, he makes vermin sound like Panzer units trying some new formation.

Freed from copy editing, then, Midge proceeds to read the world at large, the way any good Portis protagonist would—but his job training means his observations are that much more acute. He contemplates spelling errors (a strange man hands him a card that reads, inscrutably, “adios AMIGO and watch out for the FLORR!”), the abysmal Spanish-language skills of his traveling companion, Dr. Reo Symes, and the bizarrely mangled locutions of the chummy Father Jackie (e.g., wanter instead of water). Encountering an emergency flood relief effort, Midge fervently pitches in, but is nevertheless distracted when a British officer reprimands someone “to stay away from his vehicles ‘in future’—rather than ‘in the future.’” It’s funny enough the first time; when a similar omission occurs twelve pages later, after Midge discovers Norma in the hospital (“I would have to take that up with doctor—not ‘with the doctor’”), the repetition alleviates, if just for an instant, the unspoken sadness that’s dawning on him.

In British Honduras, Midge meets Melba, the friend of Dr. Symes’s mother. At Symes’s insistence, he reads two of her stories, and like an amateur Don Foster, he notes certain compositional tendencies:

Melba had broken the transition problem wide open by starting every paragraph with “Moreover.” She freely used “the former” and “the latter” and every time I ran into one of them I had to backtrack to see whom she was talking about. She was also fond of “inasmuch” and “crestfallen.”

Like all good copy editors, Midge is something of a pedant; nevertheless he seems more to relish than disdain such human details. He may debate, at length, some nicety of Civil War lore, but he rarely passes judgment on the people he meets, even when they forget his name: Dr. Symes calls him Speed; an addled Dupree mistakes him for Burke (yet another copy editor); for some reason, Father Jackie thinks his name is Brad. But names are important, as a character asserts in Masters of Atlantis. Midge notes the nominal errors with exclamation points, but no real outrage, until the end of his quest, when a dazed Norma calls him by Dupree’s first name—not just once, but repeatedly. It’s the only slip that really hurts.

“I was interested in everything,” Midge confesses early on, and in the book’s final paragraph, right before his quietly devastating revelation which colors all that has come before, Midge notes that upon his return to Little Rock he finally received his BA, and is contemplating graduate work in plate tectonics. He wants to literally read the world, to study its layers and its lives.

II. THE BALLOONIST

At age nine, a daydreaming Portis conducted underwater breathing experiments at Smackover Creek—a life-saving measure, rehearsed in the eventuality of pursuit by Axis nasties. The toponym, he explains in “Combinations of Jacksons” (published in the May 1999 Atlantic), is “an Arkansas rendering of ‘chemin couvert,’ covered path, or road.’”

Few could have predicted that after the brisk gestation of Norwood and True Grit, eleven years would pass before The Dog of the South emerged, a period that constitutes a chemin couvert of sorts. Silence, with side orders of cunning and exile, can lend luster to a writer’s work. Deep processes are afoot, some calculus of genius or madness, penury or plenty. Given the Central American trail of Dog and Gringos, and the occult mischief of Masters, one imagines Portis hitting the road, unearthing pre-Columbian glazeware, eavesdropping in hotel bars—and reading, reading, reading: Ignatius Donnelly’s Atlantis and Colonel James Churchward’s Lost Continent of Mu, special-interest magazines like the ufological Gamma Bulletin, dense books “with footnotes longer than the text proper,” to say nothing of the whole of Romanian fiction, which contains “not a single novel with a coherent plot.”

That earlier Portisian lag, alas, is now officially smaller than the one between 1991’s Gringos and whatever he’s currently working on. In Portis’s last book to date, Jimmy Burns observes of a fellow expat:

Frank didn’t write anything, or at least he didn’t publish anything… The Olmecs didn’t like to show their art around either. They buried it twenty-five feet deep in the earth and came back with spades to check up on it every ten years or so, to make sure it was still there, unviolated. Then they covered it up again.

Is a new cycle of Portisian activity on the horizon, at the end of a decade-and-change? The recent magazine appearances of “Combinations of Jacksons” (1999) and “Motel Life, Lower Reaches” (2003), memoiristic pieces that bookend the Overlook reprint project, is enough to make one wonder whether (or if you’re me, pray that) Portis is writing at length about his life.

Maybe he’ll fill in the blanks, reveal what he’s been up to all these years, though if anyone understands the character of silence, the value of secrets, it’s Charles Portis. The Dog of the South contains its own Portis doppelgänger—its own commentary on authorial mystique—in the figure of John Selmer Dix, MA, the elusive writer of With Wings as Eagles, which he penned entirely on a bus, a board across his lap, traveling from Dallas to L.A. and back again for a year. His whereabouts remain a mystery; assorted reported sightings, like those of Bigfoot or Nessie, cannot be taken at face value. Dr. Reo Symes, the most vigorous, wildly comic jabberjaw in all of Portisland, is Wings’s unlikely champion (“pure nitro,” he calls it)—a huckster on the skids who maintains an unlikely reverence for what appears to be nothing more than a salesman’s primer and its reticent creator.

Symes’s limitless patter circles the indissoluble truths contained in this criminally overlooked document, and his earnest-rabid claims for With Wings as Eagles sound not unlike those of Portis fanatics to the uninitiated: “Read it, then read it again. … The Three T’s. The Five Don’ts. The Seven Elements. Stoking the fires of the U.S.S. Reality. Making the Pep Squad and staying on it.” All else in the world of letters is “foul grunting.” When Midge modestly counters that Shakespeare is considered the greatest writer who ever lived, the doctor responds without hesitation, “Dix puts William Shakespeare in the shithouse.” Midge, “still on the alert for chance messages,” reads a few pages of Symes’s copy of Wings, but finds its dialectical materialism a touch opaque:

He said you must save your money but you must not be afraid to spend it either, and at the same time you must give no thought to money. A lot of his stuff was formulated in this way. You must do this and that, two contrary things, and you must also be careful to do neither.

*

As important to Symes as the visible text is what happened after its publication, the story behind the story, during the time when Dix “repudiated all his early stuff, said Wings was nothing but trash, and didn’t write another line, they say, for twelve years.” Symes has an alternate theory: He believes Dix continued writing, at greater length and with even more intense insight, but “for some reason that we can’t understand yet he wanted to hold it all back from the reading public, let them squeal how they may.” Thousands of pages repose in Dix’s large tin trunk—which, of course, is nowhere to be found.

*

Portis’s trunk resurfaces, after a fashion, in his next book, Masters of Atlantis (1985), which sustains its seemingly one-joke premise through tireless comic invention and an ever-shifting narrative focus. At once the oddest ball among his works and a full-vent treatment of themes common to Dog and Gringos, a clearinghouse of obscurantist scribblings and a satire that skewers without malice, Portis’s sprawling third novel loosely follows the life of Lamar Jimmerson, whose eventual sedentary existence is in perverse contrast to the typical Portis rambler. Jimmerson’s destiny crystallizes after the First World War, when a grateful derilect gives him a booklet crammed with Greek and triangles—an Nth-generation copy of the Codex Pappus, containing the wisdom of lost Atlantis. Portis’s inspired tweaking of subterranean belief systems touches on alchemy, lost-continent lore, and reams of secret-society mumbo-jumbo. The original codex, written untold millennia ago, survived its civilization’s destruction in an ivory casket, which eventually washed ashore in Egypt, to be decoded after much effort by none other than Hermes Trismegistus (the mythical figure deified by the Egyptians as Thoth, the Greeks as Hermes, and the Romans as Mercury). Hermes became the first modern master of the Gnomon Society, which counts among its elite ranks Pythagoras, Cagliostro, and, as it happens, Lamar Jimmerson of Gary, Indiana.

That the document is bunk is the obvious joke, but Portis wraps it in antic bolts of faith and failure. Indeed, Masters of Atlantis works as a thoughtful, whimsical companion to Frances A. Yates’s Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition (1964), a study of the magical and occult reaches of Renaissance thought. Yates lays her cards on the table, explaining that the “returning movement of the Renaissance with which this book will be concerned, the return to a pure golden age of magic [i.e., the supposed era of ancient Egyptian wisdom], was based on a radical error of dating… This huge historical error was to have amazing results.”

The amazing result in Masters is an alternately deadpan and high-flying pageant of secret sharers, unreadable tracts,[12] and highly dubious theories, determining the rise and fall—and rise?—of an institution insulated from the American century unfolding outside by nothing more than the unshakeable belief of its adherents. The adepti cultivate their secrecy and self-regard by maintaining rules against dissemination to outsiders, or “Perfect Strangers,” a code as strict as it is arbitrary. For instance, the Romanian-born alchemist Golescu, a caretaker at the Naval Observatory, would seem a shoo-in for Gnomonic acceptance. His achievements read like a variation on Symes’s catalogue of Dixian wisdom:

Through Golescuvian analysis he had been able to make positive identification of the Third Murderer in Macbeth and of the Fourth Man in Nebuchadnezzer’s fiery furnace. He had found the Lost Word of Freemasonry and uttered it more than once, into the air, the Incommunicable Word of the Cabalists, the Verbum Ineffabile. The enigmatic quatrains of Nostradamus were an open book to him. He had a pretty good idea of what the Oracle of Ammon had told Alexander.

But Golescu doesn’t make the cut. He knows too much—or at least says too much. His strident claims betray an insufficiently covered path. The point of the Verbum Ineffabile—the unspeakable word— is that you don’t say it.

Most mortals, it seems, are doomed to remain Perfect Strangers, but at least there’s the possibility of writing something oneself, a validating work of comprehensive greatness. In Gringos, freelance bounty hunter and former antiquities dealer Jimmy Burns journeys to the Inaccessible City of Dawn, bringing along his friend Doc Flandin, an ailing Mexico hand. Doc is ever on the lookout for the Mayan equivalent of Dix’s tin trunk or the Hermetically unsealed casket—a fabled cache of lost libros that would provide further pieces to the puzzle of that vast and vanished civilization. Burns doubts any such books even exist. In any case, Doc claims to be nearly finished with his own “grand synthesis” of Mexican history, a scholarly tour de force explaining the truth behind myths and answering ancient riddles; among other things, Doc’s book would “tell us who the Olmecs really were, appearing suddenly out of the darkness, and why they carved those colossal heads that looked like Fernando Valenzuela of the Los Angeles Dodgers.”

Somewhere in limbo, apart from or behind the printed ephemera—confession magazines and pre-1960 detective novels and something called Fun With Magnets—that crop up in Portis’s novels more frequently than any work of high literature, is a dream library stocked entirely with vanished books and unwritten ones, impossible genius texts that tantalize from across the void. Chances are that Doc’s unfinished manuscript will join the rest of those ghostly titles. But time doesn’t always run out, and at least once the dream becomes manifest. Mattie Ross waits half a century to write True Grit, and during those years the factual grit of her life story at last forms a pearl. Though Portis’s compositional timeframe isn’t quite as long as Mattie’s, his periodic absences from the thrum of publication help give each one of his books what those Burmese journalist ants call a “nacreous glaze,” a shimmering coat of perfect strangeness.

*

Portis has published a single work of fiction since Gringos—“I Don’t Talk Service No More,” a spare, haunting short story that appeared in the May 1996 Atlantic. The unnamed narrator, an institutionalized Korean War veteran, sneaks into the hospital library every night to make long-distance calls to his fellow squad members, participants in something called the Fox Company Raid. He remembers their names, though some other details have grown hazy. At the end of this call, his fellow raider “asked me how it was here. He wanted to know how it was in this place and I told him it wasn’t so bad. It’s not so bad here if you have the keys. For a long time I didn’t have the keys.”

Instead of closure, the last sentence casts a pall over the story, and the mention of keys conjures the great locked enigmas drifting through Portis’s last three books.

In Dog, Symes disputes an alleged Dix sighting, musing, “Where were all his keys?”(According to Dixian lore, the great author, wise with answers, never went anywhere without a jumbo key ring on his belt.)

The “Service” narrator’s resounding isolation connects with the loneliness found in so many Portis characters. Norwood Pratt and Jimmy Burns, wry loners capable of brute force, wind up married and in more or less optimistic situations. But happiness eludes the other protagonists. Lamar Jimmerson and most of the Gnomons in Masters of Atlantis can’t form mature emotional attachments; Jimmerson barely notices as his wife leaves him and his son avoids him. And how is it that The Dog of the South, Portis’s finest comic achievement, subtly shades into melancholy? When Midge finds Norma, by chance, in the hospital, he calls it a “concentrated place of misery”; his earlier angst-free, even chipper take on his cuckoldry suddenly shifts, in her presence, to a terrible feeling of rejection. The mere fact of his being strikes her as wearisome:

“I don’t feel like talking right now.”

“We don’t have to talk. I’ll get a chair and just sit here.”

“Yes, but I’ll know you’re there.”

Dog’s last two lines erase miles of cheer that have come before. True Grit’s matter-of-fact final sentence (“This ends my true account of how I avenged Frank Ross’s blood over in the Choctaw Nation when snow was on the ground”) harbors a more cosmic sadness; as pathetic fallacy, it feels like an American cousin to the faintly falling snow that closes Joyce’s “The Dead.” Portis carries over this precipitous finish to his own life in “Combinations of Jacksons.” A “peevish old coot” himself now, he peers back over the years to when his Uncle Sat showed him scale maps of tiny Japan and the immense U.S., to dispel his boyhood fears of a protracted war. The last lines run: “I can see the winter stubble in his fields, too, on that dreary January day in 1942. Broken stalks and a few dirty white shreds of bumblebee cotton. Everyone who was there is dead and buried now except me.”

Portis is careful to keep the tears at bay with laughter; to borrow the impromptu skeet targets from Rooster and company, he’s a literary corn dodger. In Dog, Dr. Symes’s mother, a missionary, periodically grills Midge on his knowledge of the Bible, a knowledge he repeatedly professes not to have. “Think about this,” she says, pointedly fixing his thoughts to the matter of last things. “All the little animals of your youth are long dead.” Her companion Melba promptly emends the truism: “Except for turtles.”

The statement, at once hilariously random but completely realistic, neutralizes the threat of gloom; it’s the sort of bull’s-eye silliness that pitches Portis’s reality a few feet above that of his fellow page-blackeners. Significantly, he gives Lamar Jimmerson some experience with skyey matters: Masters of Atlantis opens with the young man in France during the First World War, “serving first with the Balloon Section, stumbling about in open fields holding one end of a long rope.”

The truth is up there—well, maybe. (Gringos, among its other virtues, navigates UFO culture with more than cursory knowledge and without easy condescension.) Of all the moments when Portis’s prose turns lighter than air, my personal favorite involves the aforementioned Golescu, whose chaotic turn in Masters of Atlantis gives the book an early-inning jolt. In addition to claiming membership in various sub rosa brotherhoods, some of them seemingly contradictory, Golescu possesses the talents of a “multiple mental marvel,” to borrow magician Ricky Jay’s term. Asking for “two shits of pepper,” he takes pencils in hands and demonstrates for a bemused Lamar Jimmerson his ambidexterity and capacity for cerebral acrobatics, in a rapid-fire paragraph of undiluted laughing gas. It’s what Dr. Symes would have called pure nitro.

“See, not only is Golescu writing with both hands but he is also looking at you and conversing with you at the same time in a most natural way. Hello, good morning, how are you? Good morning, Captain, how are you today, very fine, thank you. And here is Golescu still writing and at the same time having his joke on the telephone. Hello, yes, good morning, this is the Naval Observatory but no, I am very sorry, I do not know the time. Nine-thirty, ten, who knows? Good morning, that is a beautiful dog, sir, can I know his name, please? Good morning and you, madam, the capital of Delaware is Dover. In America the seat of government is not always the first city. I give you Washington for another. And now if you would like to speak to me a sequence of random numbers, numbers of two digits, I will not only continue to look at you and converse with you in this easy way but I will write the numbers as given with one hand and reversed with the other hand while I am at the same time adding the numbers and giving you running totals of both columns, how do you like that? Faster, please, more numbers, for Golescu this is nothing…”

Read it, then read it again—at a spittle-flecked rush, with a mild Lugosi accent—and observe how everything turns into nothing, how all that is solid melts into air.

- [1] Many of the biographical details about Portis in this piece have been gleaned from this leisurely interview, conducted by Roy Reed on May 31, 2001. ↩

- [2] Whereas Kerouac was said to have been more passenger than driver, Portis knows his cars inside out, and his oeuvre overflows with automotive asides. Even the Gazette interview is graced with these vehicular discursions: Speaking of his stint at the Northwest Arkansas Times, Portis conjures up the vehicle he drove to work in, a 1950 Chevrolet convertible,“with the vertical radio in the dash and the leaking top,” and notes the species-wide “gearshift linkage that was always locking up, especially in second gear.” ↩

- [3] The new Portable Sixties Reader, ed. Ann Charters (Penguin, 2003), does not mention Portis at all. ↩

- [4] Mattie also has strong opinions on particular political matters, but the issues could not be at a more distant remove for the general reader in 1968 (or today), lending an air of comedy and verisimilitude. On Grover Cleveland: “He brought a good deal of misery to the land in the Panic of ’93 but I am not ashamed to own that my family supported him and has stayed with the Democrats right on through, up to and including Governor Alfred Smith, and not only because of Joe Robinson.” ↩

- [5] If the film of True Grit somewhat revises the book, the less-known screen adaptation of Norwood (Jack Haley, Jr., 1970), also scripted by Marguerite Roberts, scrambles both Norwood and True Grit. Glen Campbell (Grit’s LaBoeuf) here plays Norwood, and Kim Darby (Mattie) is Rita Lee Chipman; Mattie’s unacknowledged teenage longing for LaBoeuf (“If he is still alive and should happen to read these pages, I will be happy to hear from him,” Mattie writes at the novel’s close) becomes consummated in Norwood, or just about. Roberts’s Grit script shunted Mattie in favor of the bigger-than-life Rooster; for this film the screenwriter dilutes some of Norwood’s cool by revealing that Rita Lee has been made pregnant by another man before they meet—a significant, possibly feminist tweak of the original plot. (Incidentally, the contra-hippie theme that runs through Portis, made more explicit in Gringos, is elaborated in this film, most notably when Campbell-as-Norwood takes the stage after a numbing sitar exhibition. He sings a good-timey country number presciently called “Repo Man” to the uncomprehending, wigged-out crowd, until a more lysergically inclined combo unseats him.) As it’s unlikely I’ll ever have the chance to write

about this film again, let it be noted that the date of Norwood’s theatrical release, a year after Midnight Cowboy won the Academy Award for Best Picture, lends Campbell-as-Norwood a certain Voightian frisson during the scenes in New York, where he sticks out like a Stetsoned sore thumb. Which makes the bit in Cowboy where Voight regards himself in the mirror and says approvingly, “John Wayne,” a sort of anticipatory gloss on Wayne co-star Campbell’s future appearance in Gotham. (The celluloid True Grit also spawned a 1975 sequel, Rooster Cogburn, starring Wayne and Katharine Hepburn.) ↩ - [6] Toward the end of Norwood, a conversational non sequitur seems to anticipate True Grit’s heroine. Someone mentions a Welsh doctor to the British-born midget Ratner: “Cousin Mattie corresponded with him for quite a long time. Lord, he may be dead now. That was about 1912.” ↩

- [7] In books and in blood, as in this analysis from Masters:“One’s father was invariably a better man than oneself, and one’s grandfather better still.” ↩

- [8] Travel writers, not to say homo britannicus, get ribbed by Portis again in “Motel Life, Lower Reaches,” part of the Oxford American’s relaunch issue (January-February 2003). Describing a cheap motel in New Mexico, he notes a small population of “British journalists named Clive, Colin, or Fiona, scribbling notes and getting things wrong for their journey books about the real America, that old and elusive theme.” ↩

- [9] Portis is well aware of the seemingly disproportionate effects of punctuational caprice. In Masters of Atlantis,Whit and Adele Gluters’ suitcase bears their surname in caps and quotes, leading to this flight of fancy: “Babcock wondered about the quotation marks. Decorative strokes? Mere flourishes? Perhaps theirs was a stage name. Wasn’t Whit an actor? The bag did have a kind of backstage look to it. Or a pen

name. Or perhaps this was just a handy way of setting themselves apart from ordinary Gluters, a way of saying that in all of Gluterdom they were the Gluters, or perhaps the enclosure was to emphasize the team aspect, to indicate that ‘THE GLUTERS’ were not quite the same thing as the Gluters, that together they were an entity different from, and greater than the raw sum of Whit and Adele, or it might be that the

name was a professional tag expressive of their work, a new word they had coined, a new infinitive, to gluter, or to glute, descriptive of some

new social malady they had defined or some new clinical technique they had pioneered, as in their mass Glutering sessions or their breakthrough treatment of Glutered wives or their controversial Glute therapy. The Gluters were only too ready to discuss their personal affairs and no doubt would have been happy to explain the significance off the quotation marks, had they been asked, but Babcock said nothing. He was not one to pry.” ↩ - [10] Midge himself, with his rules against record

playing after nine p.m. and aversion to dancing,

is a deviation from the norm, or from Norma—

at least in the eyes of his mother-in-law, who

calls him a “pill.” ↩ - [11] At a small museum in Mexico, Midge finds Dupree’s comments in the guestbook: “A big gyp. Most boring exhibition in North America.” ↩

- [12] Many years after the publication of Gnomonism Today, a sharp-eyed disciple discovers that the printers have omitted every other page. ↩