Lisa Russ Spaar’s last book of poems, Blue Venus, dwelled primarily in memory, meditation, and the mind. While her new book follows suit, it is also intensely bodied, uncovering the material alongside the metaphysical. Spaar’s language has become more muscular, more erotic, and more insistently visceral, as if by attending to the particularity of words she could conjure them into being. In a sense, she does. The poems of Satin Cash are so attuned to the natural world that hills become “script,” the bark of a sycamore reveals “a stuccoed font,” and a stream serves as “a transcript.” If such textuality suggests that nature must be read with care, Spaar is too philosophical a poet to accept even her own interpretations, recognizing the implicit mystery attached to every word and thing. Thus, in response to the noise of sparrows, one speaker asks, “Noun or verb, that singing?”

Good question. Whether the dazzling singing throughout Satin Cash represents noun or verb is the inquiry that informs these lyrics. After all, what is a lyric poem, an object to behold or words in action? Fixing her ecstatic energies on short lyrics, mostly composed of couplets, Spaar tests the form’s temporal restrictions with language that reaches through etymological and poetic histories. In “How Was Your Day,” we discover “that pessaric vault / of swallowed stars” hides an archaic erotic reference; pessaric derives from a late Latin word for female contraception. And the ghosts of master poets abound, from the Dickinson epigraph that gives the collection its name (“I pay – in Satin Cash – / You did not state – your price –”) to the title of a poem lifted out of Hopkins’s journal (“Cold. Resolved to be a religious”). That Spaar sounds like no other poet writing today has less to do with her debts to the past than her idiosyncratic eye and ear: “we are novice, tongues fugal // and devout as two mockingbirds / in chevron surplices.”

She also tests spatial restrictions with unresolvable questions that challenge a poem’s apparent closure: “Is suffering only brief as longing?” “How might [she] woo / and… pursue & sing & win?” “What am I seeking / when I extend / my soul’s yes yes / toward you / brilliant, electrified, / and hopelessly solitary?” This last question points to the quandary of who speaks, and to whom; the poet resists easy identification of either “you” or “I.” Both are “hopelessly solitary.” In “Rendezvous,” for example, Spaar thwarts the romantic relationship that the title evokes by displacing the “you”: “The pomegranate fuse / of dusk on the wall // behind you— and you— / within—like a secret side // of the sky… / What do I believe?” Though we come to recognize “the pomegranate fuse” as “dusk on the wall,” pronouns receive no such line-by-line fine-tuning, and the “you” grows increasingly indistinguishable. Is the “you” before the wall also the “you – within,” or are they distinct? “You” could be the beloved, or the speaker, or God. The confusion (or conflation) is not at all coy, and leads to a more pressing question. “What do I believe?” doesn’t merely signal a spiritual turn so much as a reaction to the very language the poet makes and unmakes. The question of faith therefore arrives at the question of poetry. It’s no accident that the title “Rendezvous” both replays the question of “noun or verb?” and gives it a provisional answer: all of the above.

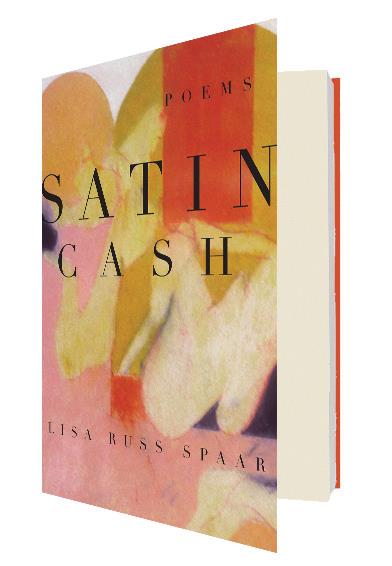

Format: 72 pp., paperback; Size: 5 1⁄2” x 8″; Price: $14.00; Publisher: Persea Books; Editor: Gabriel Fried; Print run: 1,500; Book design: Dinah Fried; Typeface: Electra; Author’s favorite Emily Dickinson line: “No Rose, yet felt myself a’bloom, / No Bird – yet rode in Ether –” (two-line variant added to a master letter, 1861); Growing in the poet’s garden: everything from old-stock bridal-wreath spirea to Brazilian verbena; Representative lines: “If there is a precedent for being, / perhaps it is in this boreal timbre // leveling the spine, lawlessly / conjuring the ghostly bodies to which // you were once attached / before they became – unlikely –”