Mark Leyner

[writer]

Part I.

It has been almost fifteen years since Mark Leyner’s last novel was published. Many authors have gone longer between books—Thomas Pynchon went seventeen years between Gravity’s Rainbow and Vineland—yet most authors who have left public life did not have quite as public a persona as Mark Leyner once did.

With pages thick in perverse, pop-artifact-studded automatic writing, his 1990 collection, My Cousin, My Gastroenterologist, still reads as it did then, as a midnight movie on fast-forward, told through non-sequitur skits and saturated with advertising jargon honed from the author’s years spent as a copywriter. At his best, Leyner would go on to capture, and atomize, the Manic Panic millennialism of the Clinton era.

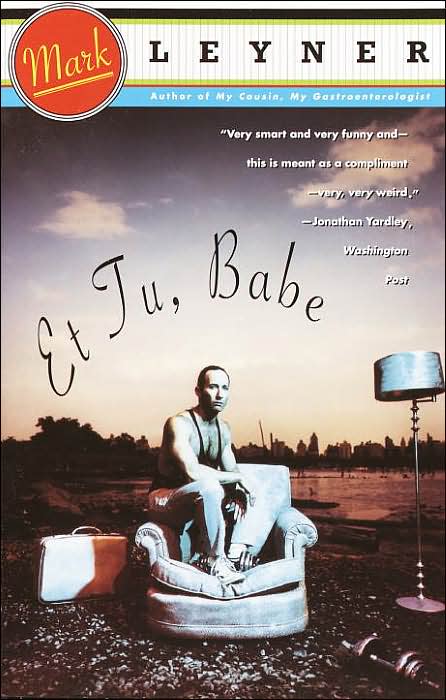

After Leyner’s breakout hit, he established a fictional Mark Leyner character in his novels, composed of signature riffs wedged into self-referential frameworks: Mark Leyner, world-famous author and corporate brand, in Et Tu, Babe; and thirteen-year-old Mark Leyner, literal enfant terrible, in 1997’s The Tetherballs of Bougainville. Then the one-time poet truly joined the mass media when he started writing scripts, including the divisive 2008 John Cusack film, War, Inc. Audiences expecting a sequel to Cusack’s previous assassin rom-com, Grosse Pointe Blank, instead encountered a frenzied update of Dr. Strangelove for the age of Blackwater and indeterminate incarceration.

In Leyner’s most recent novel, The Sugar Frosted Nutsack, he has created a pantheon of new gods (“The God of Dermatology,” for example) who toy with everyone from Red Sox Ted Williams’s frozen head to the novel’s central character, a paranoid mortal in New Jersey named Ike Karton. Told in a poetic, recursive style, The Sugar Frosted Nutsack is Leyner’s most complex work to date, and his most raw. For a novel about a fiction that contains all of existence, Leyner’s cosmological reality show intriguingly lacks his most famous creation: Mark Leyner.

When we met at Manhattan’s Old Town Bar last April, I knew I wouldn’t be interviewing the exact Mark Leyner from two-decades-old magazine profiles. The author I met was as much a middle-aged father—nervous and humble at the prospect of talking about his return to fiction—as he was a writer who could effortlessly weave Jersey Shore and The Iliad into an improv thesis on storytelling. —Brian Joseph Davis

THE BELIEVER: Writing about gods and myth is very much in the tradition of classic poetics, which is what you originally worked in. Going back, even before I Smell Esther Williams, when did humor creep into your writing? Baudelaire and Rimbaud are not innately funny guys.

MARK LEYNER: No, I have a feeling they were not particularly fun to hang out with. I realized, at the age you realize these things, I had a capability of making people laugh. Once you realize that, you don’t want to stop. It feels too good. “What did I just do? I want to do that again!” So there was a kind of crucial time—and it very much has to do with me trying to write prose—when I wanted to write something as linguistically eventful as poetry. That was my embarkation point toward, and I say this in all humility, what is unique about my work.

BLVR: Coming of age in the 1970s, what comedy spoke to you? I ask because I’ve always wondered about the influence of something like the early National Lampoon and that window where the avant-garde and comedy crossed over.

ML: I don’t think I was a devotee of comedy at that time, or any kind of contemporary, oddball, or transgressive comedy. I can tell you what things I loved as a kid. Those things tend to be much more meaningful, or enduringly meaningful, to me. If you asked me what I thought was a great example of American surrealism, I would say Chuck Jones.

BLVR: And Spike Jonze? All the Joneses?

ML: Yes, Andruw Jones of the Yankees. He’s very funny. I’d also say Charles Fleischer cartoons, and the sort of stand-up comedy on TV that anyone sitting in a living room in the late ’60s or early ’70s would see, comedians that you would watch on a talk show, like Rodney Dangerfield. Stand-up comedy had an interesting effect on me in terms of how I started to think about constructing things, because I really loved the interstices, the linkages, or lack thereof.

BLVR: Poetry and comedy are very much related in their dependence on language.

ML: They are very much related. I’m reading this book from the 1940s, The History of Surrealism by Maurice Nadeau; it’s wonderfully erudite, and throughout it makes the point that comedy is effortlessly surreal. Now, I wasn’t thinking these things at the time, but I was very interested, when I started doing whatever you’d call what I do, in those elements that make cohesive a stand-up routine. Sometimes it’s just a refrain, an arbitrary thing. And we know these things so well, like the phrases What’re you gonna do?or What’s up with that? That can link a list of fifteen or twenty things. It’s only the later style of comedy where there’s a naked lack of linkage, but in an old Rodney Dangerfield routine it’s just bits linked by his animus toward his wife or mother-in-law—you know, hackneyed things that comedians hate now. But these links did get me thinking about how it might be possible to have explosive or incandescent imagery with some kind of narrative drive. I don’t think I’ve written a book that was as pure and intransigent an example of how I wanted to write as The Sugar Frosted Nutsack, which is odd, as here I am, and I ain’t a kid. But maybe that’s why?

BLVR: You killed the character of “Mark Leyner” at the end of The Tetherballs of Bougainville, and in the new novel there is no Leyner character. Despite a fourteen-year gap, it seems like you had a consistent plan for where your writing was going.

ML: I know it seems like I made some great religious repudiation of fiction writing. I wish! I should. But it’s a very easy thing to explain. In terms of the work, I did feel like I should stop for a while. I thought at the time, looking at I Smell Esther Williams through The Tetherballs of Bougainville: Here’s a full demonstration of these postulates; here it is, to the extent that I’m able to do this and show how this might be done; and OK, that’s good for a while. I also remember trying to resist this as a career. It is my life. The most deeply felt, most profoundly felt thing that I do is this work, but I was trying to resist this idea of having a new book every couple of years so you could renew your membership.

BLVR: It’s easy to have that panic, though.

ML: It is. And when I had my daughter and started thinking about money in a certain way, some opportunities to write scripts came up, and I saw script writing as a tangential adventure, a more lucrative version of journalism or teaching. The idea of me doing that seemed much more outlandish than script writing—I’m not a good teacher.

This adventure isn’t over; I’m still working on some projects, but something interesting happened to me, and it’s a great deus ex machina. I got hit by a car in L.A. when we were doing postproduction on War, Inc., which completely fucked my knee up. I flew back and I couldn’t walk for a while and just started reading in a different way. It was an enormously galvanizing experience to me, and I decided: it’s time. Enough time had passed, and I had ideas on how to proceed without just redoing something I’d already done. I was making progress on the novel—it was due sometime—and I had at least a hundred pages of notes for what I was feeling was the last third of the book. Then I got an incredible case of the flu, or maybe I’m just being vain about it. But this is my version of the flu, and I’m lying in bed, and I can be very dramatic when I’m sick. I moan and thrash and ask people to bring me things. I’m hot, then cold. I couldn’t eat anything. My wife brought me food from McDonald’s and Dunkin’ Donuts and I couldn’t eat even that. I had a complete, universal revulsion about everything, including my book. Not what I had already but all my plans for it. It was an enormous problem, and I decided on a radical upheaval in the book, which turned out to be the perfect thing. I can’t imagine what the book would have been like if I hadn’t done that. It involved inventing two characters.

One of those that had been very peripheral but became very important is Meir Poznak. I needed a character to come and dramatize or express my revulsion at a long, well-crafted denouement. It was sickening me that I would fall prey to that! The book is fated from the beginning, and I was very clear about this. I wanted the reader to feel as if everyone knows this story, as it’s an epic based on a myth.

When you read The Iliad now, it’s not like you say, “I can’t wait to find out what happens to this Achilles guy.” Everyone knows. It’s in the introduction! So I wanted that to be part of the book. Everyone knows, and I repeat it a trillion times: Ike wants to be the martyred hero, not only waiting for but eagerly awaiting his demise at the hands of—as in the mind of any great paranoid—the Mossad. The refrains and repetitions are there to give the idea of the story being folkloric. If people asked me what it was like when I was writing, which is a better question than what’s it about, I would say: it’s like a book you would get, an old book, with an introduction about the mythology that the epic is based on. And the book itself is not necessarily the epic. It’s about the epic. I realized that if that’s the given of the book, wouldn’t that mean that once you allow for marginalia, or something like Talmudic commentary, it would begin to be this creature that’s embracing and devouring everything?