I. Ain’t Got Long to Stay Here

by Stanley Booth

Death has mewed behind my footsteps since I was child. Or written its name on the wall: was it a regional postbellum practice to have sepia photographs taken of newborns, usually wearing what I later learned was called christening attire, who succumbed after only a few months on this planet? I don’t know, but they seemed a familial domestic fixture and were usually hung in spare bedrooms. “Why do I always have to sleep with the dead baby?” I remember asking, on yet another visit to yet another relative. I was further confused by the inherent gender issue: “Why do they all wear skirts? Are they all girls?”

My great-grandmother complicated things even more. Obviously a girl at one time, she didn’t die until I was thirteen, and by then she seemed older than God—especially because she, too, dressed habitually in robes. Granny lived on a vast country plantation and would buy anything sold from a car. City or country, it pays to be a smart shopper, except when it comes to cure-alls, though she doubtless demanded a discount. Her death was followed by her son’s, my famously lazy great-uncle Bunyan, the family’s Biblical scholar and collector of the Saturday Evening Post from time immemorial. “Bunyan knows the Bible,” she would say. “But Bunyan don’t live the Bible.” No one knows how he died, except that he was found in a chair, his body partially devoured by fire ants.

More details, and fairly interesting ones, surround my father’s demise, which was caused by my mother. She called on the last Thursday night in June 2005. Diann, my wife, answered the phone, listened without speaking for about a minute, and handed the receiver to me. I heard my mother’s voice. “Darling?” she purred. “I want to ask you something. There’s a man in the bedroom, and he says he’s Stanley Booth. He says he’s either you or Daddy, but I’ve never seen him before in my life. And Daddy’s gone, and he’s been gone for a couple of days. But both of the cars are here.”

My father was eighty-eight, my mother a year younger. For the better part of twelve months, my mother had been saying that my father had Alzheimer’s disease, and their doctor agreed, though he said the condition was only incipient. My mother, I learned too late, had senile dementia. My father had what he called “the wobblies,” and I’d brought him a walker, which enabled him to creep around the house. But my mother said he’d disappeared, wandered off somewhere, and I knew, given his physical state, that was impossible.

During the evening before she called, I’d had most of a bottle of Pinot Grigio. Nothing ever frightened me so badly as what she told me. Suddenly nauseated, I lay down on the floor and felt every last one of my pores open. All at once my body and clothes were soaking wet.

“Call Ernest,” said Diann. Ernest Gilbert, our attorney, the man who presided at our wedding and to whom we refer as “His Holiness,” suggested that we dial 911 immediately. We hadn’t done so in the first place because we had no idea what to say. “Help! My mother’s brain has fallen out and she can’t pick it up!” “Give them your parents’ address,” Ernest advised patiently, “and tell them there’s been an emergency there.”

Within twenty minutes, we met a full squad of personnel, along with various vehicles and their flashing lights, in my parents’ driveway. Strangely, one of the policemen was an amateur magician whom I’d known since, years before, my daughter and I had met him at a demonstration he’d given for guests of the local library. Having someone there I knew, especially a magician, made the ordeal easier.

My father wasn’t dead, but he lasted less than a week. My mother had given him a pillow and a blanket on the floor and left him there for seventy-two hours, the same span of time he was allowed to stay in the hospital. Summarily ejected despite the muscles that were “crushed” (the medical term) during his ordeal, he couldn’t walk or do much else, but we were most grateful that his physician was able to secure a bed for him in the nursing wing of the best local assisted living facility. We thought it obvious that my mother should join him there in the non-acute section, which offered the equivalent of small apartments. No pets allowed.

For at least two years, Diann and I had made post-Mass, Saturday evening visits to their enormous Mediterranean-style home, and my parents were either to be found in the bedroom, watching the Weather Channel, or in the small nook off the kitchen, eating Raisin Bran. Diann was puzzled by the contrast between these paltry meals and the well-stocked, double-wide pantry, and I explained that it was an indication of my parents’ upbringing during the Depression, akin to my father’s ability to tell you, at any time of any day, the precise amount in his various bank accounts.

Can after can of tuna, soup, vegetables, plus multiple packets of freeze-dried, alfredo-flavored noodles—nothing ever seemed to have been taken out of the larder and cooked. Its floor was notable because of its overflowing bowl of Meow Mix.

I’d been instructed by my father on his deathbed to return to the house and take the shotguns there home with us. “Your mother,” he said, “is ultra-confused.” This, of course, we knew, and perhaps most definitely when we left to follow the ambulance that took him to the hospital on that humid midnight. “It’s dark,” she said, following us outside. I grasped her hand and, after we moved toward one of the driveway’s lanterns, showed her my watch. “I thought it was nine in the morning,” she responded, a note of suspicion in her voice.

Diann sat with her while I waited with my father for the EMTs to arrive. She later told me that my mother kept pushing her red wallet between the cushion and the side of the chair in which she was sitting. Diann asked why she hadn’t called on any friends for help. “Sometimes people will pretend to be your friends just to get your money,” she whispered.

Within a week of hospitalization, then transfer to a nursing home, my father died. His doctor told us that six months previously he had advised both of them to enter an assisted living facility. “They had the good sense never to come back,” he advised us. In fact, we learned that they had stopped going to their cardiac rehab program, church, everywhere except to the grocery store and my mother’s beauty parlor. Each time we visited their house, the same scenario: my parents, the Weather Channel or the Raisin Bran, and Angel, the cat. Cats, being naturally neat, don’t like messes. Angel did the best she could to remedy the one she inadvertently made each time she ate. Thank God the water bowl was filled only to a manageable level; otherwise, she would have drowned or died of dehydration.

I took my mother food several times after my father died. She remained as resistant to the idea of assisted living as she had when my father was alive. She didn’t want, she said, to leave her “nice things.” All of which were covered with dust.

***

Among the missing: Dewey Phillips (who played the first Elvis Presley record eleven times in a row), Brian Jones, Otis Redding, Gram Parsons, Charlie Freeman, Mike Makris, Mike Alexander, Miss Frances Markert, Jimi Hendrix, Dumar Jardine, Shawn Miller, Ian Stewart, Joe Newton, Walter Smith, Isaac Hayes, Shelby Foote, Levon Helm, Douglas “Duck” Dunn, Doc Watson, various aunts, uncles and classmates, one of the few nurses who treated me like a human being when I was hospitalized after breaking my back again, and Jerry Wexler, the record producer for Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, and also my surrogate father. As of this writing, what we grimly call the Blakely-Booth Household Body Count has reached sixty-two in slightly less than three years and includes many others, eighteen by suicide. A duo of Diann’s belovèds remains Larry Brown and Barry Hannah, the latter dying, like Jim Dickinson—not to mention the former poetry editor of the Oxford American, Jimmy Pitts—of massive coronaries at unexpectedly early ages. Pinetop Perkins, Hubert Sumlin, Honeyboy Edwards—whom Diann once met, and said her small white hand disappeared into what looked like an enormous, and enormously gentle, black paw; an electric shock went up her arm, she further reports, when she realized that this was probably the same hand that last touched Robert Johnson’s.

Barry and Alex Chilton—whom I’d known perhaps a little too well in his Memphis days and had to eject forcibly from my home several times before he reached twenty-one—died days apart from each other. Between the double parentheses that constitute “the facts, ma’am, just the facts,” Diann lost her best friends from high school and college, but neither had remained in close touch, as she had with Larry and Barry, and as regards Alex, you’ll have to read her part of this essay. For the moment, all I can reveal is that she sat for two weeks at the kitchen table, fingering and trying to re-read letters from Larry and Barry without much success: fierce she may be, but when those she loves suddenly disappear from the planet, she weeps and weeps for days on end, lights candles, murmurs Voodoo Episcopalian prayers …

***

Jerry died on August 15th, 2008 at the age of ninety-one, and not quite a year later, my own best friend from Memphis State, Jim, the record producer, had two heart attacks and a triple bypass, during which he died and was revived four times. Then he died again, like Jerry, on August 15th at Methodist Hospital in Memphis: his great heart, sealed in 300+ pounds of walking barbeque, simply quit beating. Eerily enough, he died one year to the day after Jerry. “Dylan, the Stones … I’ve had a good run, haven’t I?” Jim said in our last phone conversation.

He asked that his tombstone be inscribed with the following: “I’m not dead; I’m just not here.” Or, as Jimi put the matter in “Voodoo Child (Slight Return),” “If I don’t see you no more in this world / I’ll see you in the next one / And don’t be late.” Which suggests that hope remains for us all. And that we should keep an eye on the clock.

II. P.S.

by Diann Blakely

When Dylan accepted his three Grammys for Time Out of Mind, he not only thanked Jim Dickinson, the album’s keyboardist, but also called him “my brother.” Jim’s talents in this arena and as a producer made him legendary, though to most his fame is restricted to having played the piano on a 5:41 Rolling Stones song called “Wild Horses.” You might say that we first met there. Less than two decades later, Jim growled his way into my house, ears, and heart with “Down in Mississippi,” a track on one of Oxford American’s most stellar annual compilation discs. Jim chose his company as carefully as Dylan, Keith, and Stanley (Booth, my husband), and on the 1997 Southern Sampler he joins forces with Skip James, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Carl Perkins, the Meters, Phineas Newborn, Jr., and Lucinda Williams in “Pineola,” her dirge for Frank Stanford, the suicide whose poems retain an ur-Southern surrealistic landscape of levees and battlefields.

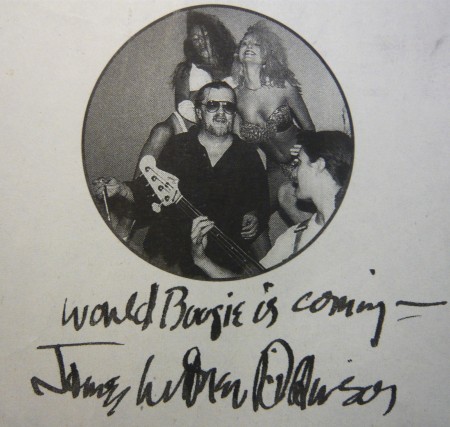

Jim serves as a pinnacle—though he would probably prefer the image of a gigantic circus tent—in the history of the American vernacular music, though this second image comes from Furry Lewis, who averred that the circus would never be unbroken. Furthermore, Jim deserves what Keith Richards once said could serve as epitaph for all great bluesmen (and women): “He passed it on.” Some day there will be a plaque marking where his two trailers stood in Mississippi, one in which he and Mary Lindsay lived and raised Cody and Luther, a/k/a “The North Mississippi Allstars” et alia, and the other which Jim used as a studio. “Zebra Ranch” it should read, as the home from which Jim practiced and preached his truest gospel: “World boogie is coming!” Perhaps Keith’s words could serve as a postscript.

Stanley Booth’s The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones, with a new introduction by Greil Marcus, was recently re-issued by Canongate in the UK / Australia / Canada, as well as Italy, Spain, and France. A Cappella will be following suit in 2014 with a 30th anniversary edition. Diann Blakely’s most recent collection of poems, Cities of Flesh and the Dead, won the Poetry Society of America’s Alice Fay Di Castagnola Award and the seventh annual Elixir Press Judge’s Prize.