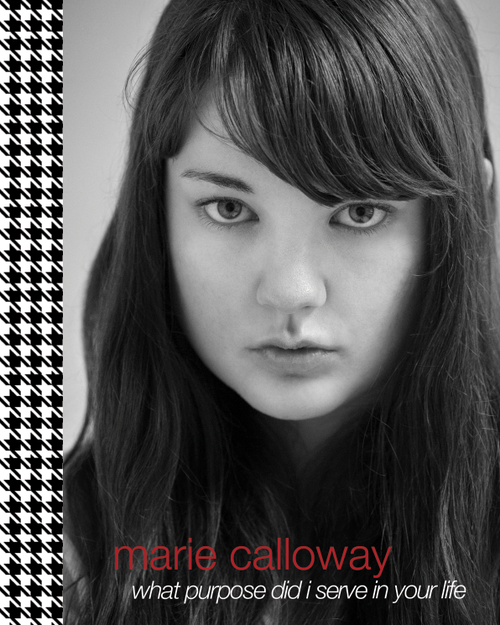

What Purpose Did I Serve in Your Life by Marie Calloway is due out from Tyrant Books in June. It’s a collection of stories and visual collages which make up a novel, depicting the life (especially the interior and sex life) of a young woman named “Marie Calloway.” Her story, “Adrien Brody,” was one of the most widely discussed stories online last year. The book is harrowing, intense, and written in clean and elegant prose. In January, Tyrant Books publisher Giancarlo DiTrapano, known for publishing books by Blake Butler, Atticus Lish, Sam Michel, and Eugene Marten, among others, was notified by his printer that they would not print the book due to “content.”

– Brandon Hobson

THE BELIEVER: What is your response to this printing debacle Gian is having to deal with? What do you think about all the resistance?

MARIE CALLOWAY: I don’t really have that much of a response. I was surprised. I didn’t know that that sort of thing happened. I think it’s sad that we live in a world where men can steal and distribute and publish photos of women without their permission all over the Internet and even in print and make a lot of money doing so, but half naked photos that I took of myself are deemed “obscene.”

BLVR: How long did you spend working on What Purpose Did I Serve in Your Life?

MC: I spent about three years writing this book. Some parts of it took longer than others. One story in it, “Adrien Brody,” was written over six months where I didn’t do much besides write it. To make a collage took only around a week though. Partly because they were reflections of thoughts and ideas I’d had for years that I just needed to find a way to express (like displaying many screenshots from guys on Facebook talking about their sexual fantasies, though I guess that was more of just an image and feeling I liked).

BLVR: The book feels more like a sort of manifesto of pieces put together in book form rather than a novel structure.

MC: It’s not a traditional novel, but I think you can see that it all runs together to form a cohesive whole in a way, kind of like Jesus’ Son does.

BLVR: So are you a Denis Johnson fan? Who are some of your literary heroes?

MC: I’ve talked a lot about liking Joyce Maynard’s autobiography. The title of my book is a reference to it. I guess that was the book that gave me a lot of courage, like a belief that I could write in a way that was different than what they teach you in creative writing class. For a long time I’ve really liked Simone de Beauvoir (she writes amazing novels), Raymond Carver, Yukio Mishima, Nick Hornby, and Tolstoy. Lately I like to read Mary McCarthy, Graham Greene, Chris Kraus, Colette, and Francois Sagan. Chris Kraus compared my work to that of Colette and Francois Sagan… I liked Sheila Heti’s novel a lot. My boyfriend works in publishing and gives me books to read like Imaginative Qualities of Actual Things by Gilbert Sorrentino, but I don’t know how interested I am…

BLVR: Can you talk a bit about why you chose to name the narrator Marie Calloway?

MC: To me it reads like fiction. It is fiction. Of course, it’s based on my life but if you asked me to write a nonfiction account of the same experiences it would be a very different book. There’s just a different style with fiction and nonfiction. And a good number of things are not pulled from my own life. I struggled for a long time as to how to express this, but the Marie Calloway in the book is not “me”, but a narrator. And the narrator narrates in a way that I wouldn’t in a non fiction story. For instance, the narrator lacks self awareness in a scenario but I will write other details in a story to convey what I’m trying to say. Tropic of Capricorn by Henry Miller is fiction and the character is named “Henry Miller.” Kate Zambreno said there’s a strange obsession with women’s writing. Much more than with male writers, people are weirdly invested in figuring out how much of the story is “true” versus fiction. It seems like you can be criticized simultaneously for “lying” about things you wrote, but also for not making things “fictional” enough. I don’t see why it matters at all, from a reader’s POV.

BLVR: How do the pictures of you work in the overall context of the book’s structure? What purpose do you want them to serve?

MC: The pictures feel as essential to me as the text. I was always interested in including pictures with writing. Something about it is very interesting. I really liked working with Gian, who let me publish lower quality cell phone and web camera photos which I think are visually more interesting than something more posed. Cosey Fanni Tutti, when she was young, did mixed media art involving nude portraits of herself, saying that those pictures would make her art feel more “complete” in a sense and also allow her to express things with her own images so she wouldn’t have to use the images of other women (she hinted at that as being exploitative of other women). I really identify with all of that… I also think using my pictures is interesting, especially for the cover, because I’m not really “mainstream beautiful.” Like, I’ve read things men have written about the cover already, about how they don’t like it because I’m “ugly.” I find it really interesting. And with the cover being a portrait of my face, part of this was done because I know I will be accused a lot of narcissism. It was sort of a reflexive response to all that.

BLVR: I know you worked in a dungeon in New York. Can you talk about that, and maybe how it relates to your work if at all?

MC: There’s not a lot to say because I was only there briefly. All of the women who worked there were really confident and beautiful…Like sexy goth girl models. It’s amazing how much there is to learn about BDSM. It’s really kind of an art form. But the business itself was shady. I worked at, from what I know, what is maybe the most respected dungeon in NYC, and still things would happen like the dungeon manager sending new girls into sessions with abusive clients without telling them about the client’s past bad behavior. And there were horror stories of girls being tied up and beaten by clients until they fainted and just left there for hours until someone found them. And just the process of having an introduction with clients and then them turning me down for being too fat (and the manager not being shy about telling me that), and the manager screaming at me if I was caught without lipstick. It was a really weird and intense place. I liked learning to use a flog and beautiful girls practicing tying me up, etc. You can make a lot of money. One girl I knew at the dungeon had a client come every week just to worship her feet for five hours at a time and she took home half a grand.

BVLR: Wow. Is there anything you took from that experience for your book?

MC: Not really. I guess I’m interested in the female dom/male sub dynamic, and how superficially it can seem like a total reverse of gender roles and maybe even subversive or something, but in the end it was mostly really young girls being paid to dress and act the way older, maybe more powerful men paid them to dress and act. This shouldn’t be taken to mean I don’t see at least some women who work at dungeons as having agency and enjoying their jobs and feeling fulfilled from them. But it was a struggle, at least some of the time, to be treated properly by the managers and clients. I feel like people think of me as someone who really believes in a “sex as empowerment” philosophy, like Sasha Grey or something, when actually I feel like I’m much more what a lot of liberal feminists would call “sex negative” than most women I know. By the way, it seems fitting to add here something about exploitation, or self-exploitation. There’s just something “off” about equating the act of spending three years writing a book with the act of someone exploiting themselves by drunkenly flashing the camera for “Girls Gone Wild” or something. It seems like an intellectually dishonest argument made not out of concern about young women being exploited, but something more sinister and gross.