Australian photographic artist Polixeni Papapetrou, whose Process interview was featured in January 2013’s issue of the Believer, has tantalized her international following for years with haunting, otherworldly imagery recapturing, recasting, and recreating childhood reverie. In her most recent exhibition, a solo show on till June at Jenkins Johnson Gallery in New York City, Papapetrou has combined chimerical pieces from Between Worlds, where pondering animalistic creatures splash out from their natural landscapes loud with feeling, with pieces from her latest series, The Ghilies, where animalism has retreated into something subtler and more spiritual. Stories From the Other Side craftily combines images of exteriorized longing with images of interiorized yielding.

Writer and media maker Caia Hagel has written several articles on Papapetrou and her work; through their long correspondence, they have become spirited pen pals. They caught up at the NYC opening—where Hagel, unable to resist, asked Papapetrou a few more questions.

(Papapetrou with her model children, Solomon and Olympia. Photo by Robert Nelson.)

THE BELIEVER: You traveled across the world to attend your opening. How was it?

POLIXENI PAPAPETROU: I was delighted to meet people at my opening who came because they wanted to look at the photographs. It was reassuring that most of the questions asked of me were about ideas rather than technique, although that is also a good question! There was a terrific opening address by Susan Bright, who spoke about my connection to the Australian landscape, among other things related to humans and especially children. It was good for the people at the opening to hear about the Australian landscape and to feel that it gave them insight into the works.

BLVR: What kinds of ideas did people ask you about?

PP: In particular I was asked about the meaning of the ghillie. And it was quite hard to explain, because while the origin of the word has something to do with a helpmate, a ghillie suit, is a type of camouflage clothing designed to resemble heavy foliage. It is used in the military for camouflage purposes, but it is also adopted now in a popular way, such as in acting out roles from video games and in paintballing games. The suit is typically a net covered in loose strips of cloth or twine. The suits can be augmented with foliage from the area to further enhance the camouflage aspect. The military, snipers, hunters, and gamers wear the suits to blend into their surroundings or to conceal themselves from their enemies or prey.

People were very curious to know how I first came across this suit and how it is used. I may have mentioned already that my son started to talk about dressing up as a sniper in a ghillie suit, a folly or fantasy that was inspired by the video game Call of Duty. I soon realized that he wanted this fantasy to become a reality, and after I bought him a suit he wanted to be photographed in the bush, completely camouflaged. But we compromised and he allowed me to photograph him silhouetted against the landscape. I couldn’t bear the thought of suppressing his presence completely. And then I discovered that if he stood in the ghillie on an open platform, his presence was bizarrely exaggerated, as if somehow essentially a figure, not necessarily a person, but an essentialized human eminence who also embodies nature. I love the fact that the ghillie is thought to reference Ghillie Dhu, the traditional Scottish deity of trees and the forest. I think that the figure in these works takes on a spirituality connected with the land. I’ve thought of the figure as a spirit being.

(The Ghillies, Ocean Man, 2013)

BLVR: When we met in Brisbane in February, you told me that The Ghillies relates to your mourning of [your son] Solomon’s growing up. Can you explain?

PP: I think that there comes a point in the life of every young person to break away from the intimacy that they share with their parents. It is not to say that the intimacy is lost, but that it needs to change as children forge an autonomous identity and make their way into the adult world. In a sense the physical connectedness that you feel with your children as a mother changes as they become independent. I miss their childhood. The transition into adulthood is so exciting and remarkable to witness as parent, but a pivotal stage in their life is has now passed and it is this that I miss.

(The Ghillies, Shrub Man, 2013)

BLVR: Maybe related to this—you always seem to be surrounded by gorgeous young boys, Why do you think that is?

PP: I had not noticed this before you raised it. Perhaps I am just surrounded by my children’s friends, who are always welcome in our home. But young people are gorgeous anyway. I look upon youth in admiration and admire them for their curiosity about the world, their shape shifting, their ideas about the future. Sometimes I think that I stay young and in touch with contemporary culture because of my children’s interests. I’m so lucky to be surrounded by their talent and vibrancy. I love young people because they are always looking ahead, and older people because they can look back; and both make sense of the world so economically. You can learn so much from the wisdom of the young and the old. I’m just in between!

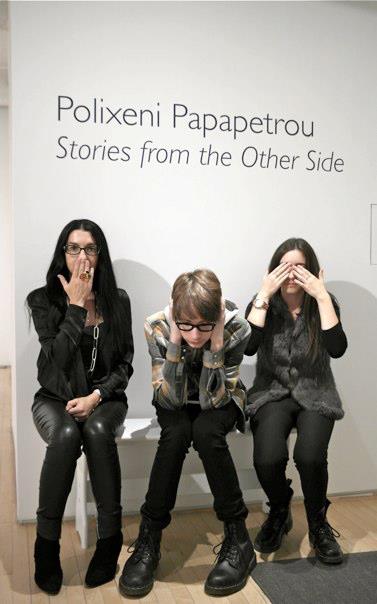

(Papapetrou surrounded by boys at the opening of Stories From the Other Side. Courtesy of Jenkins Johnson Gallery.)

BLVR: Is it weird to be standing in a space full of your own work? How do the pieces feel to you, and how do you interact with them, when they’re larger than life and on display in public?

PP: When I see my work in a gallery I often wonder how I got to this point. Sometimes the process of making the work feels like a blur, and I look at the work and wonder how I actually made it. I don’t look back and judge the work, nor do I see myself as interacting with it. I think that I go through this process when making the work, but I am interested in how other people respond. Perhaps this indicates that I become detached from the work once it is made. I feel though that once the works are in a gallery that I don’t have any control over them. I liken the experience to seeing my children growing up. Once they reach a certain age and have some independence you have very little control over them.

(Between Worlds, The Watcher, 2009)

(Between Worlds, The Watcher, 2009)