This installment of Go Forth (which is our column about indie and mainstream writers, editors, publishers, agents, booksellers and anybody else in any facet of publishing we can get to talk to us, in an effort to tell you just what all of this is like in case you should want to fly, fly into your own, dear reader) this, this episode is about a specific project.

Writer (and literary journal Monkeybicycle co-founder) Shya Scanlon once told me over dollar cans of beer in a bar in the Lower East Side that all writers of all kinds start out by writing poetry. Actually, we had already left the bar and before walking away Shya just said, “Well we all started as poets, right?” and like, walked off into the mist and this felt really profound and true to me in a way.

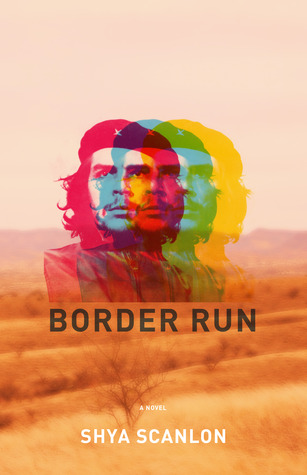

Indie writer and publisher Ryan W. Bradley is publishing Shya’s novel Border Run through his publishing outfit Artistically Declined Press and the novel is in part about immigration and a part of what makes the project so interesting is that they are donating some of the proceeds to the Immigration Advocates Network and I think that is really just swell of them. Indie should always do great things in addition to adding beautiful things to literature as a whole, no? Love, Nicolle

Nicolle: What is Border Run, what is it about?

Shya: Thanks for asking! The titular “Border Run” is a theme park at which visitors watch people re-create an illegal border crossing, and help border patrol capture them. Largely set on the grounds of this theme park, the book itself is about a three day period in which a lot happens: the owner’s ex-girlfriend comes back into town after being away for a couple years to ask a big favor; a community event is staged on the park’s grounds against the wishes of protesting local tribes; and the clone of Che Guevara tunnels into the country from Mexico. It’s a love story, basically.

Ryan: I think what’s really interesting to me about Border Run is the sense that the premise really isn’t that far off. Our society finds entertainment in many ways that are confusing, that wouldn’t be normally thought of as something that could be exploited for tourism or entertainment. Sarah Vowell’s Assassination Vacation deals with this in a nonfiction sense, but I think what Shya shows is a bleak sense that rather than question our approach to immigration we are the kind of society that would rather find a way transform it into a form of entertainment. Maybe that’s not what Shya was going for, but I think it’s an aspect of the book that feels really poignant.

Nicolle: What made you want to write this immensely complicated issue in satire?

Shya: First I want to hedge that claim a little. The book isn’t satire writ Saunders-scale, really. It does take certain observations about our way of life and magnify them, but aside from some of the southwestern clichés I play with, my treatment of most of the characters is serious – they’re not the butt of the book’s jokes. The book is actually a kind of expression of satire-fatigue: the theme park becomes the site of an actual border crossing, so to me there’s a breaking free, or overcoming, of the set-piece. Much as Che’s clone is a life after death, the border proves porous – more real as it becomes less absolute. A lot of what I’d say here runs along the lines of David Foster Wallace’s essay, “E Unibus Pluram,” in which he correctly diagnoses contemporary fiction with an inability to compete with the great ironic engine of the very popular culture it’s often attempting to lacerate. So my interest isn’t in drafting an elaborate send-up, it’s in charting a sane person’s response to insane living conditions. And anyway, as Ryan implied above, it’s no longer really fiction: in the time since the book was written, a company has actually begun providing illegal border crossing experiences. (It was covered by Vice in their Vice Guide to Travel series.)

Che is obviously right around the corner.

But that’s just one element of the book. The presiding themes are otherness and belonging, and they manifest in different ways. One of the main characters, for instance, is a Seminole Indian, but he’s almost entirely cut off from his past. Seminoles were from what’s now Florida and other southern states on the east coast, and like all the peoples living here before European settlement, their post-colonial story is a kaleidoscope of exploitation, displacement, death and making-do. He’s kind of haunted by a spectral image of his heritage, and part of his personal tragedy is being unable to know it more fully. I feel like we’re inundated with the “escape my past” narrative—it’s very American to head out on your own—and less so with characters who want to retrieve the past, but can’t. In that way, it’s also my own story. I come from a family who never really spoke of its heritage, who didn’t create family trees or keep our immigration stories alive, so I grew up not only cut off from the past, but without even a sense that anything was missing. I wanted to write about that feeling.

Nicolle: So you’re writing about how hard it can be to immigrate to a country when friends and loved ones are left behind? I remember moving the four miles from Bed-Stuy to Greenpoint and I really missed my neighbors so I bet like, running from oppression is probably much worse than that. This theme seems universal in many good novels.

Shya: Ha, yeah my bet is being a refugee is a bit more difficult than moving down the block. But when you’re a kid it can feel like the world is ending! Anyway, I wouldn’t call Border Run an immigrant book like, say, The Namesake (though maybe I could sell more copies that way—Ryan, get on it). That said, they do both have at their roots a character “caught between worlds.” Most immigrant fiction, however, is about first or second generation characters. At what point does the “immigrant experience” become more simply the “American experience”? How many generations in? I’ve read several authors decry their labeling as writers of “immigrant fiction”, and despite what I write about, I doubt I’ll ever have the same problem. Which is interesting in itself. I’m just a middle class white dude whose work will be judged largely on its own merits, free from the adjectival tyranny.

For which I’m thankful. Because though I hope people find something universal there, ultimately the book was born when I visited my father at the property he bought after my parents divorced outside of Arivaca, close to where the book takes place. The only thing between his property and the border was state land, and the entire area was riddled with border patrol. It was not uncommon to see vehicles pulled over and men and women in handcuffs sitting on the side of the street. It was a fairly intense place for me in a lot of ways—as a spectator to the strange politics, and as the son of a father in crisis–and I tried to capture some of the loneliness and sadness and pathos I felt in the book. And the beauty I witnessed. I came to love the Sonoran Desert and its inhabitants while visiting my father, and another thing I wanted to do in the book was portray that love. The desert doesn’t recognize the border, and the people who live in it on either side are alike in a very real way.

Nicolle: How does environment and scene work for you in your own writing? Do you often find inspiration from landscape and how can it be a helpful concept for writers working on their own meaningful novels?

Shya: Setting has a significant impact on my work. In fact, it would be fair to say that the novels I’ve written have been in large part paeans to place. I’ve written about Seattle quite a bit (in Forecast, for instance), but have also written about Arizona, in Border Run, and the Midwest, in a never-to-be-published novel (an excerpt of which ran in the beautifully designed magazine TRNSFR). I’ve been slow to turn my attention to New York, but it does make an appearance in the novel I’ve most recently finished. Perhaps it will get a more complete treatment soon. Anyway, these places have been dear to me, and when I’m setting fiction in them or building characters to inhabit those settings or developing thematics consistent with those settings or characters, it is out of the kind of romance I mentioned above. But the question of inspiration is tricky: landscape/geography is one of the last things I think about when beginning a book, and ends up being one of the most important organizing principles of the work over time. I don’t push it. I actually find the slow revelation of subconscious machinations one of the most satisfying aspects of art making. Environment in the broader, currently-politicized sense seems to be important, too. It’s a subject I keep revisiting, whether (weather) in the foreground or as a leitmotif. The weather isn’t just small talk anymore. It’s a metonym for the destiny of mankind. So I’m always curious about how it affects my characters, or complicates my plot, or offers up images that can deepen the texture of the narrative. Whether all this is meaningful, of course, is for a reader to decide.

Ryan: In my mind meaningful books are the only kind to publish. I publish books that I love, that I believe deserve to exist. I publish because there are books that need to be in print, that if they aren’t in print, not available to be picked up and read, will make me genuinely sad. So every book ADP publishes is vital to me personally. And having that personal tie to a book is the only way I know how to do it. ADP’s probably one of the smallest of the small presses and our funds are incredibly limited, but what we’ve got in spades is love for every book we put out. A passion for making sure those books exist.

With Border Run, and Shya’s decision to donate to IAN, it’s just an extension of that attitude, I think. I’ve long wanted to find some way to do something like this, to tie a book to a cause, because I believe in the world and it’s ability to be a better place than it is. Up to this point that opportunity hadn’t presented itself in a feasible way. We’d tried a few things in the past that didn’t work, and we had to scrap them, but when Shya told me his idea I thought: Yes! Because books make the world better, I believe. I believe art makes the world better. But there is never enough of “better,” there is always more to be done. And it’s really exciting to work with someone who is eager to connect their art with something beyond the art in terms of a world perspective.

Nicolle: How will the donation process work?

Shya: As simply as possible. For each 10 copies sold I’m going to donate $50, until 100 copies have been sold. Ryan will be notifying me after each 10th sale, and has created one of those donation thermometer things to live on the ADP site so people can mark our progress.

Once we get to 100 copies, who knows? I very well may extend the pledge indefinitely.

See more about Border Run here.

And more of the Go Forth series here.