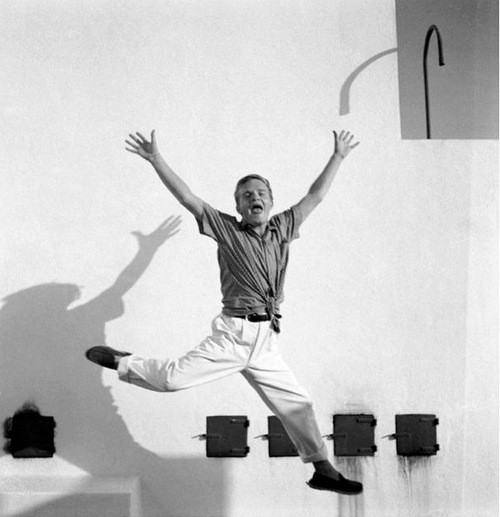

(Truman Capote in Morocco, 1949. Cecil Beaton)

The following is an excerpt from the director Curtis Harrington’s new book Nice Guys Don’t Work in Hollywood.

Jennifer Jones was giving a party for Truman Capote. Truman was in the midst of writing In Cold Blood and had decided to visit California accompanied by Alvin Dewey, the small-town sheriff he had become friendly with in Kansas. Jennifer gave the party in the big house at 1400 Tower Grove Road in Beverly Hills, which she shared with her husband David O. Selznick.

My friend Bernardine Fritz had asked me to escort her to the party. Bernardine was a woman d’un certain âge who had befriended me and often invited me to the lively tea parties she

held in her small house in Coldwater Canyon. She called herself “an old China hand,” since she had resided in Shanghai for a time in the 1930s. She had also lived in France in the 1920s where she had been friends with the likes of Isadora Duncan and Aleister Crowley. Bernardine wore a great deal of heavy Chinese jewelry, and the lobes of her ears were excessively long due to the weight of pendant earrings of jade and precious stones. She had many artistic and expatriate friends who gathered at her salons, and like most intellectual Americans who have lived abroad for great lengths of time, she had fascinating stories to tell. I felt privileged to be her friend.

Immediately after our arrival, as Bernardine was introducing me to Jennifer, I heard a high-pitched voice with a Southern accent: “Harrington, Harrington! It must be Curtis Harrington!” Truman Capote was rushing toward me from across the room with his hand outstretched. “I just love your film,” he gushed. Since at that point I had only made one feature film, Night Tide, and a few short avant-garde films, his enthusiasm was much appreciated. Later in the evening, he explained to me that he and the film critic Dwight Macdonald had read a laudatory review of Night Tide in Time magazine and sought out the film when it was playing in a 42nd Street grind house. They both loved it.

Dinner was to be served in the long galleria off the living room at a series of round tables, each seating ten. The party was an A-list Hollywood event, and I was dazzled to find myself in the company of Rosalind Russell, Natalie Wood, and Nick Dunne, among others. When I found my place card, I discovered that I was seated next to Loretta Young. I remembered that she had given a lecture when I was student at the USC...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in