The Singularity

Keegan sends me a photo of his new painting as a text message. The image is small on my phone so I have to spread my fingers across the screen to enlarge it, to see all its details, textures, the subtle wobble of its soft-curved lines. The physical painting is 70 X 60 inches but the photo on my phone is a few square centimeters, so the two images require different kinds of viewing. You stand before the painting; what’s on my phone is a compressed, glowing icon.

During the six months he’s working on this group of new paintings, Keegan often sends me images on phones – in progress shots, finished paintings, drawings. Somehow, it doesn’t seem wrong to see the work this way. The paintings are environmental and filled with color and nebulous forms – not necessarily the sort of images you’d expect to shine in small formats – but the paintings look good here, in my hand.

Maybe this is because Keegan’s visual ideas begin with what he calls “ a small bit of information" – an ancient Chinese illustration, an anecdote about the origin of Calligraphy, a drawing from a Czech picture book. The bits can come from anywhere, and Keegan is an impartial omnivore, attempting "to make no value judgment in his culling of images,” welcoming anything that comes before him – from the culturally quiet to loud, from Josef Lada to Jeff Koons to Peter Saul to Agnes Martin to Chaim Soutine. It’s a forest of visual information to navigate and he’s got the sharp, curatorial mind to cut through it and find a single, dense seed that can bloom into a painting-sized idea. When describing this process of discovery, he cites Ellsworth Kelly, who once remarked that, for him, the sight of a single leaf could inspire years worth of work.

Once he’s found the seed, Keegan begins a series of preparatory studies on paper. He slides forms around the page by transposing, photocopying, tracing, erasing, processing his visual kicks through a garden of his own idiosyncratic techniques. He likens the process of building a composition to working on a Kaoss pad, a digital, musical effects box that can twist, stretch and refract any nugget of audio into hours of ever-shifting sounds. He flattens out the dimensional ideas and adds faux-dimension to the flat ones. He builds a vocabulary of symbols – the unconsciously-active type that trigger desire and compulsion and wonder. Even the most expansive, airy work, “Hudson River (Predator® B Unmanned)” emerges from speculative headlines about a drone strike on the Hudson river.

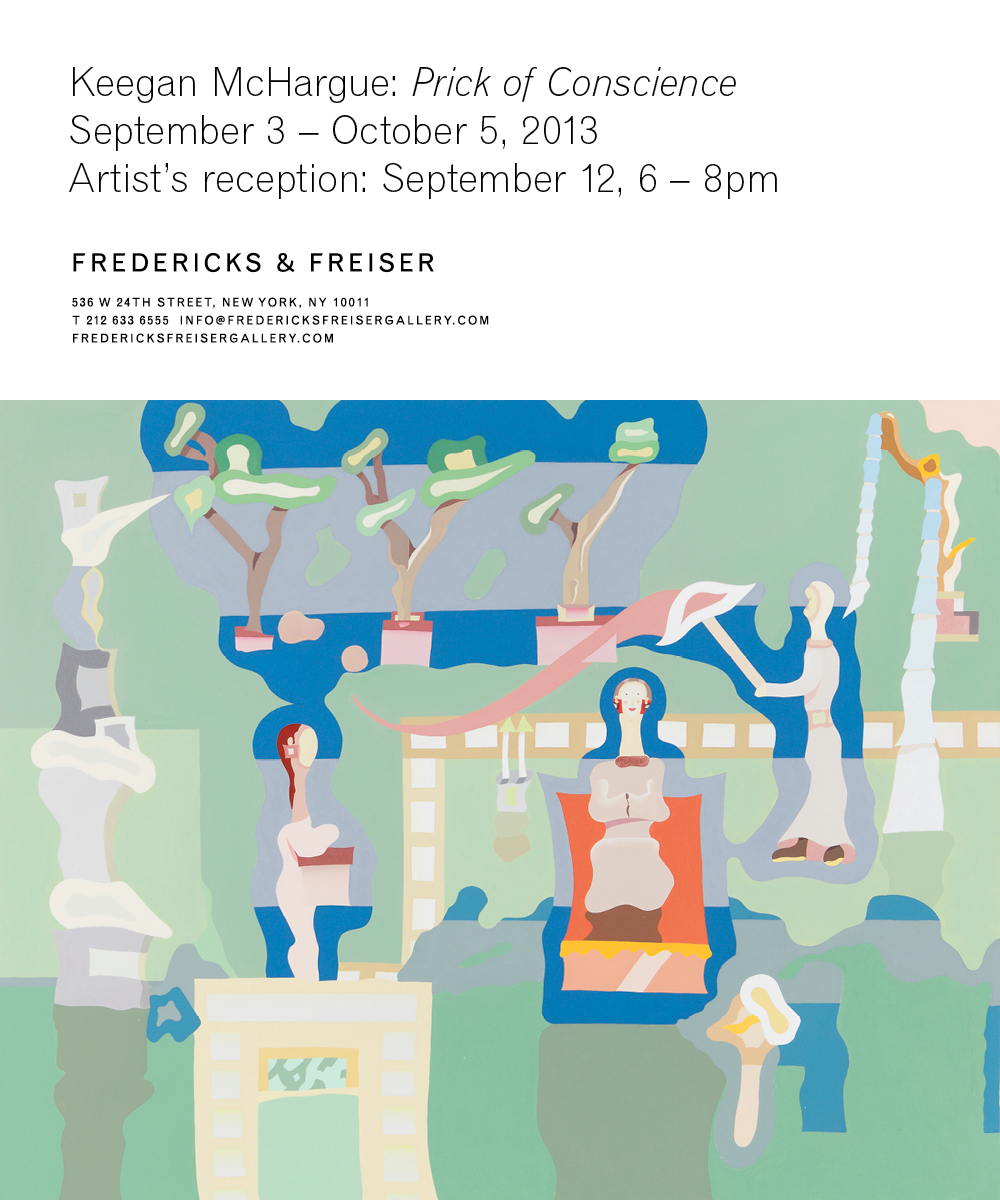

He does one thing, takes out two things. He compresses and reduces and distills the image until it functions, like an icon, on the simplest, most unfettered visual wavelengths. He thinks about the freedom inherent in minimalism while he works. It keeps his attention focused on the singularity of the idea, so that the image’s energy appears to emerge from a point somewhere deep within itself and ripple outward into a sea of visual ideas, each one nestled into its neighbor, like a liquid puzzle. The feeling of looking is not dissimilar from seeing ancient Islamic and Hindu art, where narrative and space and subject flow into a single current.

The lines, too, are liquid. What at first appears to be a straight, rigid line, is revealed, the longer you look, to veer and float. The environment gently sways between the proto-psychedelic luminance of Charles Burchfield’s watercolors and the gentle west-coast roll of Ken Price’s landscapes. Like John Wesley, Sigmar Polke, and the Cobra school, he uses the language of storybook illustration to simultaneously stabilize his work and subvert our visual comfort zones. It’s child-like, but fastidiously so, more like the constrained scrawl of Jonathan Lasker’s than the chaotic scat of Cy Twombly. The image is stirred and shaken, then shaved and cleaned, to attain the look of a pure creativity in cool, moderate balance. “This,” he says, “is what I always wanted my paintings to look like.”

When the image is a complete thought, Keegan brings it to the canvas, which has been readied with marble dust primer and stretched over aluminum bars. He executes the whole thing quickly, in a single layer of paint so thin and cleanly applied that he imagines it sliding down and off the canvas onto the floor. He doesn’t work over the paint. He doesn’t have to. The image already exists.

—Ross Simonini

You can see more of Keegan McHargue’s work on his website, and an interview in the 2010 art issue.