By Todd Hasak-Lowy

In 1999, The Sopranos premiered on HBO. Rather quickly David Chase’s story of contemporary New Jersey mob life made every previous drama ever aired on television seem trivial, superficial, and just a tad bit embarrassing. Bolder, smarter, thematically richer than anything before, “The Sopranos” gave birth to Good TV.

Good TV is not merely good TV (i.e. better-than-average TV), but TV that is so good it deserves to be taken as seriously as great films and even great Literature (yes, with a capital “L”). As such, watching Good TV and discussing Good TV are qualitatively different than watching and talking about other kinds of TV. The emergence of Good TV is a rather big deal in the recent history of American culture. It may well be one of the top two or three cultural developments of this still-young century. 1

I’ll admit I have some, as people seem to say an awful lot these days, skin in this game. I’m a writer. A writer of books. And as everyone knows, books have been getting the shit kicked out of them by movies and TV for many decades now. It seems unlikely that these visual mediums will ever fully kill books. Instead, they’ll force books to continue retreating further into their distant, trivial corner of the culture.2 So yeah, I don’t come to any conversation about TV neutrally (but who does?).

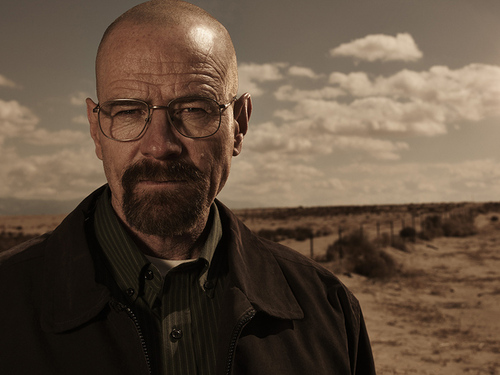

But however much my stance would seem to be informed by some primal, I-resent-you-for-kicking-the-shit-out-of-the-my-medium animosity toward TV, I should also mention that I watch TV. Not a ton of it, not every night, but I watch it, and like watching it. A lot even. Moreover, I think about it and talk about it, and, most relevant to this piece, much of what I watch is considered Good TV. Lately I’ve been watching Breaking Bad. I started on Netflix, but now, like many millions of others, I am watching it on AMC, each Sunday. 3 I am now watching it in this way because I can’t wait to see what will happen, because I do strongly believe Breaking Bad is Especially Good TV, and because the end of this show has become a Thing Of Consequence Happening Right Now In Our Culture. Reason #3 has recently swelled to the point that I can’t help wondering if Breaking Bad won’t transcend Especially Good TV and become (cue the music) Historic TV.

All this rapt watching and thinking and talking and reading about Breaking Bad as an important chapter in the short history of Good TV has got me wondering: what does it mean to invoke the concept of Good TV (whether we explicitly use the phrase “Good TV” or not 4 ) in the first place? Why are we so invested in it? Why are we getting so supremely excited about the whole thing?

Plenty could be said about Good TV programs, 5 but what interests me most are not any qualities of the shows themselves, but rather how the people who enthusiastically watch (and talk and social media-ize about) them relate to them. For most of these people, especially those of us who consume these shows with at least occasional self-consciousness, Good TV represents some of our culture’s greatest contemporary achievements. Hollywood’s best writers, along with some of America’s best writers period, are creating and writing these shows. 6 These shows possess a degree of sophistication that (at least comparatively speaking) dwarfs that of even the very best pre-Good TV good TV. Long-running, writer-driven shows have overtaken American cinema as the most prestigious strand of American visual culture, 7 revealing most of even the supposedly best American movies as risk-averse, unimaginative, and hopelessly bound by their time constraints.

Let me make one thing clear here: I think most of the Good TV I’ve watched is pretty damn good. It is certainly extremely good compared to most TV, but I will even concede that some of it—the very best of it—represents narrative art of a most impressive sort. The intricate choreography of The Wire’s vast number of story lines is, from the perspective of this writer, humbling. Breaking Bad boasts a fully realized stylistic audacity that is no less stylish and audacious for being so clearly an attempt at stylistic audacity. The final moment of Mad Men’s pilot, when Don Draper pulls into his suburban driveway and thus reveals that the overwhelmingly rich life he lives in the city represents only half of his whole life, this was a moment only a master storyteller could craft. And so, just to be clear: my interest here is not to claim that Good TV is actually aesthetically bad. Not at all.

What I’m here to claim is that we (we meaning Good TV watchers who value—knowingly or otherwise—Good TV in part because of the wider cultural esteem we believe these shows deserve) stand to benefit from even more people—and the culture as a whole—coming to concur with us that Good TV is really and truly extremely good and not just good-for-TV good. Because not so long ago most of us knew—or at least would have likely admitted in moments of complete honesty—that the best TV wasn’t all that good, or was only good in some crucially limited, lay-off-I’m-tired-after-a-long-day, good-for-TV-only way. If you don’t believe me, hunt down an episode of M*A*S*H on TV Land. My hunch is that even Hill Street Blues—the show that probably constitutes the first stone laid in the bridge between pre-Good TV and Good TV—hasn’t aged all that well (ditto for St. Elsewhere, LA Law, and ER). Those shows were in most ways soap operas that had gone to primetime finishing school. Good TV, by contrast, is something else entirely.

So what happens when we convince ourselves and others that Breaking Bad is, artistically speaking, on the level of, say, not just “Midnight Cowboy” and “The French Connection,” but Morrison’s Beloved or Roth’s American Pastoral or Delillo’s White Noise as well? How much better do we feel about regularly watching two or three Good TV shows (i.e. devoting three to six hours of our already too short week to TV) if we believe (and get others to agree with us) that we are participating in the best our culture has to offer?

Every last one of us is familiar with the statistics regarding the number of hours Americans spend watching TV. Most of us probably don’t have the greatest associations with the image of some other person (it’s always some other person) sitting—in the mostly dark, on his couch, his fat face illuminated by that pale blue glow—in front of his TV for hours on end. But the emergence of Good TV seriously dilutes, if not flat-out undoes, our guilt over watching so religiously.

Think of it this way: imagine what would happen if some of the best chefs in America decided that the present system dominating the American restaurant industry was preventing them from realizing their potential? And what if some significant number of these chefs then left their four-star restaurants and began working for M&M/Mars? What if these chefs then began producing candy bars that were so delicious, so sophisticated and delicious, so clearly the result of culinary expertise creatively and ingeniously applied, that a person who knows more than a thing or two about food might tell you, “Dude, forget that Sachertorte, you’ve got to try Alice Water’s new Stellabar, it’s a major achievement.” How excited would you be to eat a candy bar that was not only yummy but also enabled you to claim you had an educated palate, that you were eating some of the most delicious food being made anywhere in America?

Okay, I’ll admit that my analogy isn’t perfect. Junk food, even fantastical junk food, is objectively bad for you. Good TV represents, arguably, a whole-sale transformation of TV, meaning that an analogous Gordon Ramsey Snickers might actually resemble a $30/pound dark chocolate more than anything ever manufactured by Hershey’s Inc. But doesn’t part of our, um, appetite for Good TV stem from our excitement at being told (or just collectively convincing ourselves) that something bad for us is suddenly not so bad at all?

Because that’s the thing about Good TV, it’s not an either/or genre. We have our cake and eat it too. Pre-Good TV we had to choose: fun, but formulaically stupid, or smart, but dreadfully boring. Good TV is NYPD Blue crossbred with Masterpiece Theater. Good TV is low culture promoted to high, while somehow maintaining its easy-going-down qualities. We sacrifice nothing when we watch it.

The emergence of Good TV as good and good-for-you TV goes a long way toward removing the guilt of watching TV. In particular, watching Good TV is watching TV freed from the guilt of watching TV instead of reading a book. Sure, there are people that watch Good TV and still read, but there are plenty who pretty much don’t read books anymore, or who read much, much less than they might otherwise, in part because of their affection for and addiction to Good TV. Because, think about: when was the last time you were watching TV that you could not have been reading a book instead? 8 Though hardly the most strenuous activity, reading remains—at least for me and, I suspect, millions of others—more demanding than watching TV. 9

The discourse surrounding Good TV (on the web, in the traditional media, at the workplace) has become both symptom and cause of literature’s ongoing marginalization. We watch Breaking Bad not merely because it is good, but because everyone’s talking about it. Who the hell talks about books anymore? I teach creative writing in an MFA program, and half the time it’s easier to talk about TV than books with my colleagues and students there. Not because no one’s reading there, not at all, it’s just nearly impossible these days for any particular book to become a Thing Of Consequence Happening Right Now In Our Culture. 10 We may have way more channels and options on TV than every before, but the discourse surrounding TV (including Good TV) possesses centripetal force. There are 500 shows on TV, and we talk about five of them.

Which brings me to the coming denouement of Breaking Bad. Most of the conversation about the last few episodes has focused on matters restricted to character and conflict. What will happen to the law-abiding high school chemistry teacher (along with everyone in his orbit) who turned into a homicidal drug kingpin? Who will live, who will die? How will the show’s various monumental, five-seasons-in-the-making, imminent showdowns (Hank vs. Walt, Jesse vs. Walt, family vs. drug production and distribution and dishonesty and murder, etc.) be resolved? These are interesting questions, no doubt.

But Breaking Bad stands as an interesting moment in Good TV’s short history due to its potential to put some serious strain on the pleasure we most certainly take in watching this show—and others like it. Because make no mistake, Breaking Bad, however bad its breaking has been, has also been consistently and unbelievably fun. The fun of a nerdy, middle-aged white dude cranking out crystal meth of unprecedentedly premium quality. The fun of a wheelchair bound, mute, hard-ass, retired bandito telling someone to fuck-off with the help of a laminated letter chart and a bell. The fun of Mike being Mike and Saul being Saul and every one of those signature, edgy montages set to those perfectly selected, obscure, but strangely familiar tunes. Rare is the episode that doesn’t serve us up generous portions of the televised comfort food we expect and demand from each and every serving of TV drama (Good or not): cops, guns, wads of cash, high-stakes deceit, and characters flirting with irreversible disaster.

But Breaking Bad has taken all of us to a fascinating and complicated place. As everyone knows, Walter White has—yes, you all know the phrase, say it with me—gone from Mr. Chips to Scarface. And even though we’re (morally speaking) not supposed to identify with and root for him anymore, we can’t quite help it, at least I can’t. Everyone starts watching the show by identifying with Walt, because such identification is irresistible. A good man, a regular man, an underpaid, underinsured, unfairly ill, overlooked genius of a man who takes an enormous risk to provide for his soon-to-be husbandless and fatherless family. We know, from the beginning, that he is making a very questionable decision, but like all great characters, he finds himself stretched thin across a truly irresolvable dilemma. 11

For a while, then, we continued to root for Walt, even though we weren’t completely sure we should, even though we knew there was something morally bad about our identification. But as long as Gus was around, there was someone worse, someone else to root against. Plus we could convince ourselves that Walt’s badness might be temporary, that the bad Walt could recover the old, good Walt and that the family would remain together, and solvent. But by the start of this season Walt has been, plain and simple, a bad person. In other words, the breaking is pretty much over. He has broken. Been broken. Is breaking others. Whatever. Only what about the identification? Because is it just me or don’t we all still continue to pull for him? At least a little? And maybe not only with the hope that he reclaims some of his humanity. Maybe we just want him to keep on winning. 12

This last season of Breaking Bad stands apart from the previous four, because pretty much the whole season (or at least the second half of it) takes place after the main dramatic arc has been travelled. Walt is bad. Walt is really, really, really bad. And so many of the remaining questions have shifted to a different narrative plane. Now the questions are: what kind of world will Vince Gilligan have Walter White inhabit? Will it be a world where a person such as Walter is brought to justice? Seems unlikely at this point. Will it be a world where the concept of justice has any coherence at all? Will it be a world where a person can do the kind of things Walter has done and benefit from them in any way? And what price will the innocent people surrounding Walt be forced to pay? 13

The exact answers to these questions will not just resolve Breaking Bad’s place in the history of Good TV, but may push the very limits of Good TV itself as well, and in that way make watching Good TV a very different kind of exercise than it has been up until now. Because Gilligan has the potential to create an aesthetically and thematically satisfying ending that isn’t really all that much fun, that makes us realize that Great Art and Pure Pleasure don’t always (and perhaps sometimes shouldn’t) overlap. Speaking about the third-to-last episode, Grantland’s Bill Simmons said, “I was disappointed in myself as a human.” 14 There was a touch of hyperbolic sarcasm there, but make no mistake, we could find ourselves (quite literally) looking at an ending that will make us feel exactly that.

Though there may be some surprises still waiting for us, the following outcomes all seem much more likely than not: Skyler, Walt Jr., and Holly will live without their husband/father. They will never overcome their shame, resentment, and hurt. Marie’s greatest hope will be the eventual disinterment of her husband’s corpse. Walt’s master plan will realize exactly none of its goals: the family will be broken apart and his millions won’t reach (or at least won’t remain) with them. He will return with the big gun, kill the Nazis, and free or not free, kill or not kill Jesse. And recoup or not recoup all his bloodstained money. Or Walt will die, at his own hand or someone else’s. 15

But how much do any of those last either/ors even matter? Is there any scenario here in which anyone winds up with a life that anyone (i.e. any of us) would ever want? Is there any possibility of redemption anywhere here for anyone? As I see it, the final note of this show will either be extremely bleak or completely bleak. Those are the two possibilities.

And so, with one episode left, ask yourself honestly: how are you feeling about your Good TV now? The chatter in the twitter-blogo-interspheres is at a fever pitch, and much of it is saturated with a giddiness already recognizable from our conversations about the conclusions of previous Good TV programs. But we all ought to stop for a moment and accept what we are now implicated in with the case of Breaking Bad. Because it’s one thing for a world with some moral order, with some system of justice, to have couched within it a good man gone very bad. But what if this man overturns this order entirely, or at least flattens some significant corner of it and more or less gets away with it?

And what if this ending is crafted in such a way that, artistically speaking, feels like the proper ending? It’s certainly possible. I had been hoping, until recently, for the final moment of the show to be Walter’s death, but I’ve come to realize that in many ways the show will be more true to itself if it allows him to prevail, while everyone else suffers. Could it be that Historically Good TV—at least in this instance—is Good TV with the fun taken out? Good TV that makes us feel very bad about ourselves for believing that it would always remain good (if not exactly clean) fun? Good TV that fooled us into thinking that, like Walt, we could have it both ways?

Are you ready for Breaking Bad to stop being fun? Are you interested and willing to think about what it might mean—for you, for our culture, for our society—to produce and consume this kind of story by the millions? Is this entertainment? Are you truly willing to let TV As Art take you to all the places art sometimes goes? Because badness, such purely nihilistic badness, would require from you some response other than tweeting things like, “Fuck, that was insane! Can’t believe it’s over!”

What would it say about you, about all of us, if the most pressing question that surface inside these wired brain of ours once it’s the top of the hour and the next (sadly not Good) show starts is: What will replace this for me? Because in my opinion, if that’s how we respond to the end of this baddest Good TV yet, I’ll say that it wasn’t (and we aren’t) very good at all.

- All the other consequential cultural developments I can think of (from Youtube to iPods to file sharing’s demolition of the recording industry) are utterly computer/internet/mobile device related. That cluster of phenomena is no doubt way, way, way more important than the emergence of Good TV, so much so that calling these things “cultural” seriously understates their importance. ↩

- Where (i.e. in this corner) many of the books that get sustained, mainstream, commercial attention, even ostensibly serious ones, will read way more like novelizations of yet-to-be made movies than actual novels. Yes, that was a dig at a number of unnamed writers who are much more successful than me. ↩

- I’m tempted to say I’m now watching it “live,” which though technically inaccurate would I think capture what it feels like to watch these fateful broadcasts as they’re happening. ↩

- Very few (if any) people whom I know of or read or listen to use the term “Good TV” or anything similar. But there’s no question that a certain kind of unusually good (i.e. artistically ambitious, aesthetically sophisticated, unmistakably smart, etc.) TV is now talked about and celebrated in a way distinct from all sorts of otherwise occasionally good TV (e.g. sports, reality shows, sitcoms, news, etc.). Put differently, people are invoking Good TV even if they don’t acknowledge (and aren’t even conscious of the existence of) such a category. “Prestige TV” may arguably be a better name, but there’s something understated and maybe ironic and/or multivalent in the term “Good TV” that has it edging out “Prestige TV,” which admittedly remains a close second, probably due to something nearly oxymoronic in its pairing. ↩

- As mentioned, The Sopranos was the first, galvanizing instance of Good TV. The other three shows that seem destined to become first-ballot inductees into the Good TV Hall of Fame are The Wire, Mad Men, and Breaking Bad. A longer list might include Six Feet Under, Homeland, Game of Thrones, Friday Night Lights, and Downton Abbey. I say “might” because even before I got to the end of my list I could hear millions of indignant viewers losing their shit over this or that inclusion/exclusion. This imagined indignation I believe speaks to our collective investment in Good TV, however much imagined indignation might technically be unable to speak to the existence of anything actual. ↩

- And, of course, others have jumped on board. See director David Fincher’s and actor Kevin Spacey’s involvement in (the Netflix original series!) House of Cards. ↩

- Even though the Emmys enjoy precisely one-sixteenth of the Oscars’ self-important pageantry. ↩

- The Onion has printed two brilliant pieces on this topic, both of which satirize our collective, largely repressed awareness that Good TV time has colonized good, old-fashioned reading time. “Report: Watching Episode of ‘Downton Abbey’ Counts As Reading Book”. The second, which I couldn’t track down on the interweb, read something like, “Man Wishes He Had More Time To Read, He Thinks While Waiting For Next Episode of Friday Night Lights to Load on Netflix.” ↩

- There are probably a ton of reasons for this, some of which are undoubtedly neurological, and an entire second essay could easily be written just about the dynamics of watching vs. reading. So for now, just this: a lot of the contemporary literature worth reading (in my, in this case, not so humble opinion) actually (and not coincidentally) demands much more effort than not only watching Good TV but reading the other novel(ization)s presently available. George Saunders’ recent and amazing Tenth of December is a fine example. Though not radically experimental, Saunders’ stories nevertheless must be read slowly, and maybe even twice, in order to be understood on even a pretty basic, what-just-happened level. By contrast almost every episode of Good TV, however brilliant, can be easily followed by just about anyone. This isn’t to say that there aren’t subtle layers of meaning in an episode of Mad Men, but rather that these additional nuances are beamed to the viewer along with guaranteed, impossible-to-miss, juicy plot turns multiple times an hour. Most great literature pushes form, whereas most great TV revitalizes formula. ↩

- The recent exceptions to this (Harry Potter, Hunger Games, Fifty Shades of Middle-Aged Humping) were all aimed at non-literary markets. The last literary novel to breakthrough was Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom, a novel most serious readers and writers I spoke to thought was overrated (or just refused to read, because they think Franzen himself is overrated). My hunch is that the serious literary corners of our culture maintain—at least when it comes to books—a deep hostility to the marrying of high (or just really good) and mainstream cultures, such that Franzen’s inclusion in the latter disqualified him from the former (plus everyone envies him to no end, obviously). But these same people don’t have a similar problem with Good TV, they (we?) probably just think that they appreciate a show like Breaking Bad on a deeper level than most everyone else. If I had to guess, I’d say that this double standard isn’t ultimately doing the institution of literary fiction any favors when it comes to its ongoing marginalization. ↩

- And my sense is that Walter White resonates so powerfully—especially with men—because his initial bind stands as an accurate, however amplified, version of what most fathers and husbands feel today: that the ingredients now required to bake the cake of middle-class security are together unpalatable. Either the hours are much too long or the pay sucks or the job is utterly soul-crushing or the work has simply disappeared altogether. The only possible response is a series of actions that would paradoxically preclude us from remaining members of this same secure American middle class: crime, poverty, or, say, spending eight months a year driving a truck in Iraq, etc. These are desperate times. ↩

- Someone once told me that above all we want competence in our characters. Think about Hannibal Lecter. A monster, but a virtuoso monster. Who didn’t enjoy what he did inside that large cage with those poor guards? ↩

- And even the innocent people surrounding the people surrounding Walt. The sudden and horrific murder of Andrea is a perfect example of where Gilligan may well be headed here. The world of the show is consuming itself, as the forces of evil (they’re Nazis, after all) proliferate and operate unimpeded. ↩

- This comes at around the 45:50 mark of the podcast. ↩

- If things go that way, I vote for Jesse to pull the trigger. Indeed, now that Walt’s transformation is complete, Jesse has (for me anyway) become the most interesting character. He seems to have become a limit-case for suffering, precisely because he remains the final locus of meaningful morality and conscience in the entire show. ↩

Todd Hasak-Lowy is the author of a short story collection, a novel, and a book for children. He lives in Evanston, Illinois, and teaches creative writing at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.