Photo by Dan Busta.

Davy Rothbart has made a career out of collecting things: notes, people, stories, life lessons—all of them in some way found. I first came across his work when a friend left a copy of Found Magazine with a note on my desk, and I couldn’t help but find it funny, because in 2000, Rothbart started the magazine in much the same way—he found a note written for someone else on his car’s windshield, and decided to Xerox it and share it with others. The magazine, which you can also find online, publishes pretty much every kind of found note imaginable. More recently, he released his first book My Heart is An Idiot, a collection of personal essays littered with insight and humility.

Last week we spoke over the phone, me from San Francisco and Davy on the road in Boston, on his way west to Woodstock, New York.

I. Feeling As Strangers Do

THE BELIEVER: Has putting the found objects online changed the way you compile the magazine?

DAVY ROTHBART: I put the magazine together once a year as a print magazine. I do print and my friend James Molenda does the website. I’d say about half of what we receive is mailed in, the other half is scanned and e-mailed. So if somebody mails one in, it comes to me and goes into one of the magazines or the found books, if somebody e-mails it in then James considers it for the website. I know that we have the same criteria, which is to find ones that give you the most instant, powerful response. A response of strong emotion, an interesting combination of story and emotion, the hint of a narrative. Something intriguing, something to wonder about, something that gives you a powerful glimpse into somebody else’s life.

BLVR: So if it’s been online it’s not going to be published in the magazine?

DR: Exactly. It might have happened a couple of times, but generally it will either be on the website or in the magazine.

BLVR: Did you find, as the magazine grew in notoriety, that owners of the found objects began to contact you?

DR: Yeah, it’s happened a few times. When it does, they’ve been really cool about it. Either they’re a bit honored, or more often, they’re just totally mystified. Kind of wondering, “why would anyone care about these little details of my love life?” I explain to them that I can relate to it. I’ve written the same love note a hundred times myself. This one girl, she wrote to us recently, she had seen a note in an issue of Found at a friend’s house that she had written ten years before about these two guys she was dating—Chad and Steve—and she was trying to figure out which one to be with. We traded some emails and she ended up giving me a whole update. She’s like, “Well, now I’m back with Chad but Steve’s coming up this weekend to visit me so I’m not sure what’s going to happen.” It was hilarious. It’s a treat to get to meet the actual person and find out what the situation was.

BLVR: Especially because the emotions can be so intense. It makes me wonder how you cope with the emotions day-in, day-out.

DR: To me, that’s the magic of them: they’re relatable. It’s easy to go through something really intense and feel like “nobody else could possibly understand what I’m experiencing right now.” Then you read this complete stranger’s note found on the other side of the country, on the other side of the planet, and discover that some total stranger is experiencing the same kinds of things as you. It’s a really powerful feeling. I think it makes you feel less alone and there’s something really powerful about that.

BLVR: That’s one of the things I love about reading in general, you’ll read something written by someone you don’t know but they seem to have tapped into an idea that fits into your life. But to have found that in someone who doesn’t write for a profession is just as great.

DR: Totally. I think that’s why I love personal essays so much. People are sharing their own stories but their stories illuminate something about you. There’s always that question of recognition where you feel like wow, I’ve felt the same thing, I’ve been in the same situation, I relate to this. It makes you feel known – better known, better understood. That makes you feel more connected to the world.

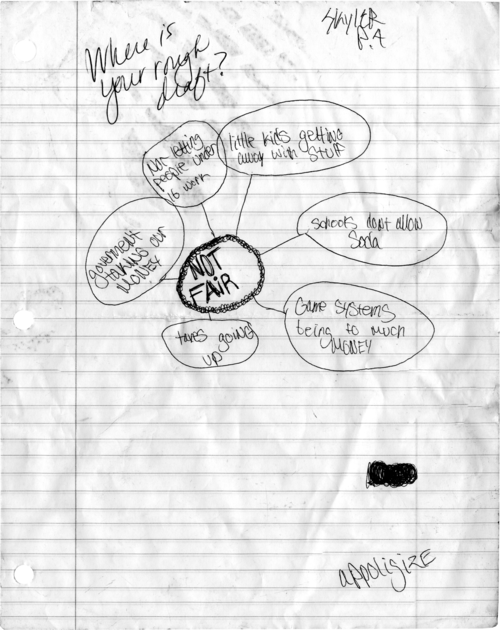

A note found by Jill in suburban Las Vegas, Nevada.

II. Found People

BLVR: About the stories in your book: many of them are centered around an object, or a person, or a moment. They seem to be a collection of things that, if found by someone else, would tell an unusual story about you and your life. Do you think, by writing the book, you were giving back to the nameless, faceless people that have inadvertently given you these insights into their lives?

DR: Absolutely. The motivation for the book of essays came from two sources. Yes, part of it is the idea that I’ve been publishing other people’s most private thoughts for the last ten years in Found Magazine and that it almost felt fair to open myself up in the same kind of way. But I also love reading personal essays like that anyway, for the reasons we’ve just discussed. I think there’s a magic in the found notes – you find a little scrap of paper blowing down the street, or the floor of the city bus and it gives you this really incredible window into this other person’s life. That said, what I’ve loved about travelling around doing these Found Magazine tours over the last ten years is the chance to brush up against actual people. It’s like having Found notes come to life when you encounter a stranger and get a chance to talk to them and hear their full stories. And so these essays, I think, are about found people and the adventures we’ve had together.

BLVR: Everyone in your book seems to be good in some way that you can’t help but react to; for example, Lon, from the fake book agency, in “Ninety-Nine Bottles of Pee.” Are you predisposed to liking people, or at least to looking for the best in them?

DR: I think most people are good. Part of it’s my outlook but part of it is objective truth. That doesn’t mean we don’t fall into moments of pettiness or anger or selfishness, but I think most people are essentially good.

BLVR: I think so, but I also think it’s the way you bring it out of them. I don’t think that instant trust is a universal trait. Yes, they might be good in some way – but it takes you to recognize that.

DR: I think all of us, me too, can learn to look for the good in people a little more.

BLVR: Has that trust ever really hurt you?

DR: I can barely remember… I mean, one time I tried to buy weed from someone in DC when I was nineteen and I bought a bag of oregano instead. [Laughs]

BLVR: If that’s the worst that’s happened then you’re all good.

DR: Yeah, I haven’t been the victim of any massive treacheries. If anyone’s let me down, it’s been myself. I think it’s our own feelings that make us the most miserable and sad and depressed. A lot of the essays in the book are about those times when I feel like I have maybe injured other people without wanting to, or done things I regret. There’s one essay, “Tarantula,” that’s probably the one I’m most proud of in a way.

BLVR: It still feels complete, though. It is obviously a tragic story but I feel like you were able to get something out of it.

DR: Yeah, I did. In the moment I thought maybe I could have done more to help save that guy’s life or something, if I hadn’t been drunk and just had sex with some random girl. But he had been dead for a while.

III. “I Try to Live Everyday Like I’m Drunk”

BLVR: Do you have any regrets? Is that something you’ve collected?

DR: I’ve done a lot of things in my life that I’m not proud of, that I wish I could take back or change. I think the best thing you can do is learn from your mistakes. I think, in life, we are doomed to repeat our mistakes over and over, but having the time to write these essays really gave me perspective. It gave me a chance to see some of the stuff that I keep doing over and over. And also, just talking about the book, touring with it, reading essays from it, it’s hard for me to lose sight of any mistakes I’ve made that I’m not happy with. I get a chance to be reacquainted with them every day so hopefully I’m less likely to repeat them.

BLVR: So you think you would recognize the signs of almost making the same mistakes?

DR: Yeah, that’s exactly how to put it. I used to not see them at all. My friends would always say stuff: “You always do this,” or “Dude, you’re a broken record about this,” and I’m like, “No, it’s different, I don’t know what you’re talking about.” But now I have a chance to get a little more insight.

BLVR: I was chatting to a friend when I was reading your book and I was trying to describe to him your tendency to wind up in fairly unusual situations and in reply he said, “I need to stop going home,” like it was the key. I understand that you’re curious by nature but how much to do you attribute the experiences you have to time and place and how much do you think is of your own making?

DR: I think it’s just always being open to adventure, being open to other people. If you’re not sure whether or not you should do something, you probably should. You don’t have to make every single day a carnival ride, but it’s generally about being more open. This old friend of mine, who hasn’t had a drink in like eight years, said “I try to live everyday like I’m drunk.” Which is kind of awesome.

BLVR: And do you think you’re open to vulnerability and mistakes in your own choices?

DR: I certainly feel open to sharing my vulnerabilities with other people. [Laughs] The first essay, “What Are You Wearing” is about this phone sex relationship I had. It’s pretty fucking embarrassing. I was really nervous about outing myself in this way, but the response was overwhelmingly positive. I think that emboldened me to write about other personal experiences and I find now, with the book out, I get these incredible e-mails everyday where people are willing to share their stories because I’ve opened myself up.

BLVR: Do you follow up on these e-mails?

DR: Yeah, sure. Someone sends me this beautiful message and, if it’s a Facebook message, I’ll see that they’re from Denver or Madison or whatever and I’m like, “Hey, I’m going to be there in a month, you should come out and get a drink.”

BLVR: Do you see a change in them? A relief that they’ve got someone to share their stories with?

DR: Yeah, it’s really fantastic. I don’t like small talk so it’s great when people come up to me at these events, they’ll give me this weird smile and be like, “I read your book, I feel like I know a lot about you.” They’ll feel comfortable sharing some very intimate and personal stories of their own. I love having a way to tap right into somebody’s most inner self, instead of the superficial stuff.

BLVR: Assuming it is your brain calling your heart an idiot, what do you think your heart would say in return?

DR: My friend Brandy, who travels with me a lot, wanted to write a book called My Penis is A Genius, which is pretty funny. But – my heart’s retort to my brain? I think it would just say, “Well, at least I’m living life.”

Found by John F. Ybarbo in South Austin, Texas.

Davy Rothbart will be in San Francisco tonight (10/10/13) at the JCC and in LA on October 24th. See more about Found Magazine and My Heart Is an Idiot online.