Following my conversation with Matt Kish about working with Tin House to produce his hefty, heavily illustrated reprint of Moby-Dick, I wanted to talk to the artist working on the next installation in the “series,” Allen Crawford, AKA Lord Whimsy. When I interviewed him over the phone shortly after my conversation with Kish, he was still in the middle of working on the art for Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself, arguably the most famous poem in the collection Leaves of Grass. I wanted to know what these books are doing differently by integrating illustration as much as they do, and to hear another artist’s perspective on what it’s like to engage with a text in this intimate, exhaustive way.

—Kylie Byrd

I. “Barracuda”

ALLEN CRAWFORD: I’ve been in the basement for the past six months so I’m actually interested what I’m going to say to anybody.

THE BELIEVER: I understand you’ve been working really hard on Leaves of Grass “Song of Myself”. How did you get involved on this project?

AC: Well, I remember when my friend met Matt Kish who did the Moby-Dick book, an illustration on every page. He came for a chat and listening to him talk, it kind of put a bug in my ear, I thought, clever Matt can’t possibly get to everything. Why don’t I give him a leg up? You know, give him a bit of a hand? Because I thought this project was an interesting idea—an interesting way to interpret the material—and to give it a fresh form. I think that’s a worthwhile thing. I mean it’s a bit of a stunt as well, there’s no getting around that, but at the same time this project is something that I’ve found forces me to engage with Whitman’s ‘Song of Myself’ in a very intensive way. There are times when I’m merely illustrating it but there are others when I’m actually interpreting or reacting to it, and that’s what I put down. Or maybe I’m just transcribing it, allowing the text to speak for itself.

It was an interesting way to approach the American canon of letters, and I thought okay, if I can put it in such grandiose terms, I’m hoping someone might actually pick up the slack, and maybe we can get another illustrator, maybe instead of it being a boy’s club, have a woman.

BLVR: Have you done an illustration project of this magnitude before?

AC: Actually I have. My wife and I did the identification deck illustrations back in 2002 when they had refurbished the Milstein Hall of Ocean Life, in the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, you know, the one with the whale in it. When they redid all of that they needed identification illustrations for their dioramas, and there were about four-hundred species that they needed drawn and rendered in digital format, so that was probably our main claim to fame. Today, most illustrators’ output tends to be pretty ephemeral—magazines, or something like that, and they’re gone in a month. There aren’t a whole lot of options in the profession that allow you to do something lasting, so to an illustrator, a permanent display in the Museum of Natural History in New York, that’s almost your Sistine Chapel.

BLVR: I see that.

AC: I remember the opening day, looking down and seeing a little toddler learning how to say “barracuda” using one of my identification keys. And I don’t mind saying I shed a tear. I was moved by that. Being the old fuddy-duddy that I am, that really moved me. The staff of the museum are all Leonardos—the diorama building is incredible. If you actually get into the back, to the offices and the studios where they do the fabrication of the displays it’s phenomenal. Whale flukes everywhere—icebergs and birds being built, it’s incredible. Santa’s workshop or something. The level of talent there’s just formidable.

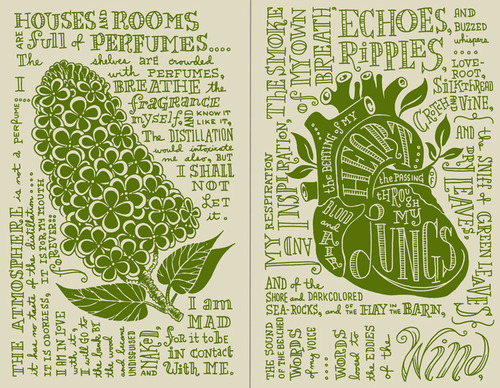

BLVR: What artistic media have you been working with on this project?

AC: Gee – pen and ink. Pencil. That’s it. It’s very simple. I have a set up downstairs in the basement and I have two draughtsboards and one’s for doing my sketching and the other one with a light board attached to it that’s all but vertical. I do ’em in two-page spreads. So the first is your pencil, in ink you make any corrections as you go, and by the time you get to the light table you’re doing those final little tweaks, and you’re getting it right where you need it to be. So it’s all on the fly. And I don’t know in advance what I’m going to do for this particular spread.

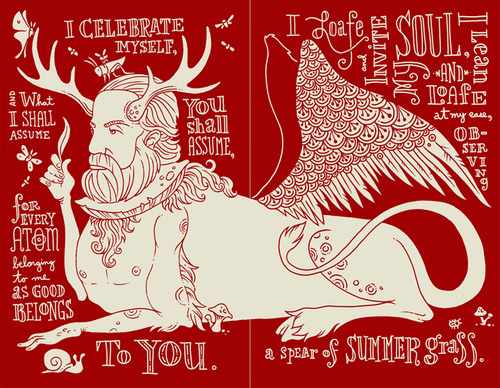

I try to treat the poem as almost a landscape, in the sense that I’m exploring this unknown territory and I’m taking field notes from the mind of Whitman. He treats “Song of Myself” as this broad, epic sweeping poem where he’s trying to include everything about American life he’s experienced. So it is a kind of landscape, a kind of world. It is a kind of continent in itself. And as you’re travelling through it, you have different impressions, your style will change, the type will change, sometimes the type will take the fore and you’ll get a very pictorial sort of a interpretation, or a symbolic one. Sometimes the image doesn’t necessarily jive, and isn’t depicting something that’s actually in the poem. I’m trying to provide a parallel narrative to Whitman’s in visual form.

II. Scramble and Hustle

BLVR: You’ve created typefaces before, is that correct?

AC: I’ve done a couple of them, that was years ago. I did one called Apogee that seems to have had a bit of a hit in the early ‘90s. I think that was launched in 1994 from t26 and used to be on rave flyers and ambient compilation albums. It was a bit of an experiment, and that was in an exhibition Mixing Messages in about 1996, I think. It’s strange because I’m a little bit all over the place – I write, I illustrate, I do videos. I’m all over the map so I don’t really make a really strong impression in any field, I’m a bit of a jack of all trades, master of none, but it makes for an interesting life, I mean if you can manage it I would recommend it. Professional dilettantes are a bit thin on the ground these days. Maybe I’m giving myself too much credit. Although – the economic realities being what they right now are I don’t have much choice, I have to have to have a lot of pots on the stove. Millennials are probably finding themselves forced into that role in order to get by. It is good though, because it forces people to have a nimbleness of mind that traditionally was something always had to have. It was only after the nineteenth century that we needed to have anything we call a job – you know, we don’t need a job you need a livin’. I would much rather scramble and hustle.

BLVR: So I understand that you chose to redraw a number of illustrations because they would have been cut off by the gutter in the printed edition.

AC: Yeah it took about two weeks. What really takes the most time is not the drawing. The hard part is working out what it is you want to do. I didn’t expect to spend so much time interpreting the first paragraphs of Whitman, because there’s so much in them… and I get cranky with Walt sometimes, you know? Why you been throwing in everything but the kitchen sink all the time? There’s too much stuff. Unlike someone who came later like William Carlos Williams, who takes a red tricycle or plums – he was more of a miniaturist, and at heart that’s more my aesthetic: I like vignettes. But someone like Williams will take one thing and look at it from lots of different angles, really study it. Walt isn’t necessarily meditating over these things as he is pointing at them. Because his scale is so much larger that he’s doing these epic sweeps and he’s saying, ‘Look at that, look at that, look at that, look at that!’ But in so doing he’s making huge compilations of objects, of stuff. It’s like a crowded attic this poem. He’s an intellectual hoarder.

BLVR: It must be harder to choose.

AC: Yeah he’s driving me crazy. But what happens is that stuff becomes inert, because I can draw whatever he’s talking about, but it doesn’t really have a resonance to it because, you know, it’s just a thing, like he’s kicking it somewhere. On the rare occasion that he does, it makes much of very easily – when he talks about ‘I guess the grass is itself a child, the produced babe of the vegetation’, it’s a very vivid image and there you go grass-baby, right on the page. Whereas when he says ‘ships’. Well. I could draw a ship, but that’s not going to be very interesting. In other words, what happens is there’s a lot of lifting on my end. I can’t just draw a damn ship. Sometimes it’s infuriating but at the same time it gives me space to come in and interpret it and run with it too.

And also I want to make sure it has a contemporary feel. I don’t want this to look like a 19th century book, I want there to be some sort of infusion of modernity in this, so that it gives his words new life, breathes a little bit of fresh air into the text. I mean he’s still relevant, people read him, much of it does feel quite modern, because he’s such an open-minded, open-hearted man. If I knew Walt I’d love the guy. I know I would. I’ve read Recollections of Walt Whitman from his later life when he lived in Camden, New Jersey, which by the way is only about fifteen miles from where I live. So I live in Whitman country. The trees he talks about in Specimen Days, I know those trees I know exactly the kind of landscape he’s in when he’s swimming in the creek, because I lived there. Sorry I lost my train of thought, I was bitchin’ about Walt.

BLVR: I think you have a point there about bringing modernity into these illustrations.

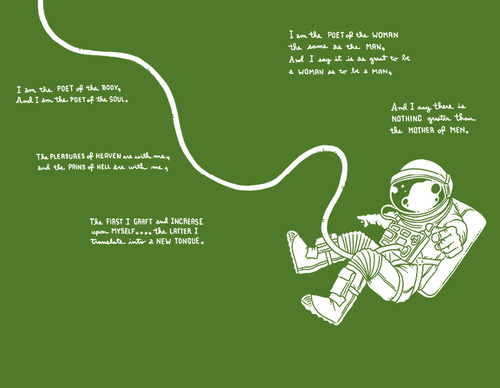

AC: I do have one key spread where I have an astronaut, with one of those umbilical cables coming out, but the text is talking about mother being the greatest of all, exalting motherhood. So we have two disparate things. The text is doing one thing, the visuals are doing another. So what we do is we create a third space in the gap between—in the interpretation: why did he draw an astronaut here? Of course, because it’s like a foetus, it’s like an embryo. Floating in a void with that umbilicus coming out, and with the giant head it’s got that babyish aspect to it. So I’m trying to be successful in that regard – to create room for people to delve between Whitman’s text and my visuals. And hopefully there’ll be enough room in there for an awful lot of interpretation.

III. The OG

BLVR: Do you intend to illustrate other poems or is “Song of Myself” the scope of the project?

AC: There’s an awful lot that I’d like to illustrate in this way, but a lot of it’s not in the public domain and I’m not sure that there’s an audience out there, or if there’s a publisher out there that would want me to do an edition of, say, John Berryman’s Dream Songs. Whereas I would love to take Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities and give it a visual terms. You know: Life: A User’s Manual would be an exciting challenge, maybe too much of a challenge actually.

BLVR: How long have you been working on this?

AC: Oh it’s slow going, and I had to take on other projects to keep the lights on. And every time I get pulled off this project it takes me three days to get back into that headspace for this, that mode, that momentum, that uninterrupted time. I really cannot wait to see this – the way I envision it is like a block of wood, that when you cut it open – you know buff-colored, hard cover on the outside, a stout little chunk of wood – that when you crack it open, there’s all of this color and variety of imagery – it’s just this lush little universe. This drab exterior, and when you open it up it’s just this little garden of earthly delights inside. I think Walt would appreciate that. I do have a friend right now whose been a collection of Whitman ephemera for decades now, unfortunately he’s terminally ill, and he’s bequeathing a lot of his collection here to a state college in New Jersey, and I’m dedicating the book to him. For the simple reason that I only dedicated a year and a half to this project, be he dedicated his whole life to the Whitman legacy, so it seemed only fair. That’s another reason I’m trying to get done as soon as possible, not to be too blunt.

BLVR: How did you come about creating your alter-ego name of Lord Whimsy?

AC: That was a lark really that grew legs and ran away from me, a jeu d’esprit? And it kind of got away from me. It was something that I did for the Philadelphia Independent about ten years ago, it was very much tongue in cheek, a caricature, and what happened over time was the mask became the face, which is kind of a very American thing, which is appropriate in the light of Whitman. Which is the American ideal of fake-it-until-you-make-it, you know, you pretend to be something and then you wake up in the morning and you are that thing, or at least a reasonable facsimile of it. And I found that’s been the case, I’ve taken on certain qualities.

I come from a working class background or at least a lower middle class background. There are two ways of being in that milieu in America. One is the very in-your-face “I’m trash and I don’t care what you think about me” strategy, and then there’s another strategy which is more common—certain strains of Southerners who are poor but kind of retain their gentility because it’s a bid for dignity for them. If you look at the documentary Harlan County USA, that was thirty miles away from where I was born, and that was all going on when I was a baby down there. My grandfather was in coal mining until we got out, so we were pretty much used as livestock. The thing is, though, those people, even in their circumstances, they still dress up on Sundays. That was their way of asserting their own self-worth, of saying, “I’m poor but I’m not trash,” and I think if there’s any vestigial that I brought along from my background it’s that.

In some neighbourhoods of Philly I’m kind of taking my life in my hands, but usually, in the African-American neighbourhoods, I’m safe as in God’s pocket because they understand where I’m coming from with that. But other enclaves aren’t so sympathetic. You know – wearing a tie and a suit anywhere in America, you’re sticking out like a sore thumb. But I think people kind of take it the wrong way—they think that I’m trying to be better than them. I’m kind of making fun of that actually, of myself—I’m kind of hiding a quaint side. So it’s been an interesting experiment, treating myself as my own lab rat. I don’t know the psychiatry or the pathology behind it. I’m sure that a psychiatrist would have a field day with it, but I like to think I’m a well-adjusted human being, and it’s been a productive neurosis.

BLVR: Are you going to be attributed as Allen Crawford or as Lord Whimsy?

AC: I think this one’s an Allen Crawford project, I don’t think anything with Lord should be anywhere near Whitman. I don’t think my second rate European should be on a first-rate American’s book, put it that way. That’s my way of bowing to Whitman, that’s my way of saying, “You’re the OG.”

See a gallery of Crawford’s images.

See more information on Whitman Illuminated: Song of Myself.