Sochi Russia, 2009. Photography by Rob Hornstra, courtesy Flatland Gallery.

As Sally Jenkins reported from Sochi as the 2014 winter games commenced, “The grim and the gorgeous coexist side by side at the Sochi Olympics. Anyone who thinks that what’s happening here is comparable to the excesses of other sports events in other places simply hasn’t seen or felt these Winter Games firsthand. The $51 billion colossus is an act of destructive grandiosity that threatens to make us all queasily complicit in crime yet simultaneously awed and intimidated.”

Among the Russian Police choir’s performance of Daft Punk’s “Get Lucky,” the race to save the hordes of stray dogs in Sochi from imminent government extermination, half-naked pictures of Putin which reportedly line hotel-goers’ bedrooms, and complaints that Olympic accommodations “fall into the chasm between global spectacle and underserved population,” never mind the distressing report from The New Republic that Irina Rodrina, the Russian Olympic figure skater who lit the flame alongside hockey goalie Vladislav Tretyak, tweeted “a racist, doctored picture of President Obama,” the opening of the Sochi Olympic Games may not be impressive for its austere landscape alone.

During what may be the most troubling Olympics to date, Putin’s high vanity has been on display from all angles—from the architecture to the pure cost of the opening ceremonies. Haunted by the egregious human rights scandal that has plagued these games since it was first announced that Sochi would host the winter Olympics in a country where “homosexualism” is an affront to “sexual sovereignty” and is punishable by arrest and jail time, Jeff Shalett’s piece for GQ, “What It’s Like To be Gay In Putin’s Russia,” offers a particularly noteworthy peek into the kind of fear which accompanies out-gay-life in Moscow. As Shalett points out, “Russia’s closet has always been deep.” “Yes, there are killings. In May, a 23-year-old man in Volgograd allegedly came out to a group of friends, who raped him with beer bottles and smashed his skull in with a stone; and in June a group of friends in Kamchatka kicked and stabbed to death a 39-year-old gay man, then burned the body. There’s a national network called Occupy Pedophilia, whose members torture gay men and post hugely popular videos of their “interrogations” online. There are countless smaller, bristling movements, with names presumptuous (God’s Will) or absurd (Homophobic Wolf). There are babushkas who throw stones, and priests who bless the stones, and police who arrest their victims.”

Being gay is considered Anti-Soviet propaganda in Russia. But, as Shallet asks, where does suggestion end and segregation begin? “The new law explicitly forbids any suggestion that queer love is equal to that of heterosexuals, but what constitutes such a suggestion? One man was charged for holding up a sign that said BEING GAY IS OK.”

From a personal stance, I have always questioned whether the U.S. diplomatic response of sending Bryan Boitano as U.S. ambassador to the games was enough of a message to convey our stance against this kind of blatant civil rights abuse. From the arrest of the Pussy Riot girls for performing a “Punk Prayer” in Moscow’s largest orthodox cathedral, to the PR stunt that was Russia’s pre-Sochi release of Greenpeace’s “Artic 30,” the group of activists and journalists who were arrested under charges of ‘hooliganism’ for protesting on a Russian offshore oil rig, I was with Masha and Nadya, in voting for the U.S. boycott of these games. And I’m Russian, just like them.

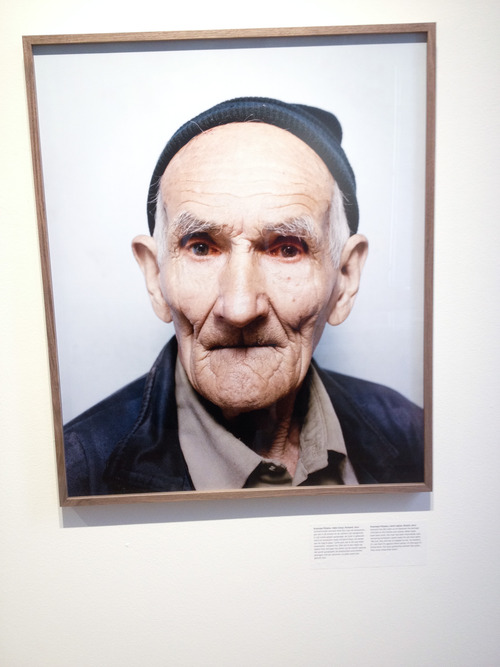

It was with this smoking gun that I recently entered Rob Hornstra’s photo exhibition at the Huis Marseille in Amsterdam. Following the cancellation of Hornstra’s show in Moscow—the photographer and his confidant were denied a visa by the Russian government—the Huis Marseille volunteered to host Hornstra’s photographs of the “Sochi Project” in their beautiful old row house. Set amidst Amsterdam’s sprawling canals, coffee-shop culture, and live-and-let-live spirit—Amsterdam’s Red Light district notably rivals Provincetown’s Commercial Street in the number of gay flags flying—Hornstra’s photographs of Russia offer a stark comparison to this Netherlandish joie de vivre, documenting as they do “the erratically-applied false eyelashes on the flamboyant Natalya Shorogova, floor supervisor at Hotel Zhemchuzhina in Sochi; the educational ‘Cosmonautics’ museum at Orlyonok, a children’s summer camp; or the simple image of a plate of prison food.” With their focus on “laying bare the Russian soul in a thousand details,” the colorful portraits of Russian prostitutes, artists, veterans, junkies, housewives and children in Hofstra’s Golden Age exhibition offer a powerful “documentation of a love-hate relationship with a colorful country and its remarkable people.” Arnold van Bruggen’s accompanying texts stand in bold contrast to the narrative of the Technicolor pageantry that was Putin’s “Russia over thousands of years” as told through the much-redacted visual history of the opening ceremonies.

Photographer Rob Hornstra and writer and video artist Arnold van Bruggen have been collaborating since 2009 to tell the story of Sochi through their technique of “slow journalism,” “establishing a solid foundation of research on and engagement with this small yet incredibly complicated region.” As van Bruggen writes, “Never before have the Olympic Games been held in a region that contrasts more strongly with the glamour of the Games than Sochi. Just twenty kilometers away is the conflict zone Abkhazia. To the east, the Caucasus Mountains stretch into obscure and impoverished breakaway republics such as North Ossetia and Chechnya. On the coast, old Soviet-era sanatoria stand shoulder to shoulder with the most expensive hotels and clubs of the Russian Riviera.” Indeed, the subtitle of The Sochi Project is An Atlas of War and Terror, and in conceiving of the exhibition Hornstra and van Bruggen set out to construct “a contemporary masterpiece of photography and journalism in the collaborative tradition of James Agee and Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange and Paul Taylor.”

What makes Hornstra’s vivid color C-prints stand out from the work of Evans or Lange is their attention as much to the humorous as to the profound. In this way, Hornstra’s work has more perhaps in common with the photographs of Martin Parr, whose oft-garish colors and satirical use of frame play with the idea of propaganda through criticism, seduction and humor. The heart of Hornstra’s photographs isn’t, as Sally Jenkins says, about reveling in Putin’s Olympics, whose purpose is “to make the ordinary citizen quail with helplessness at the power of the “new” Russian state.” Rather, the photographs aim to present the conflicting faces of a country in flux, one highly beset by poverty and the nomadic influence of popular culture inherited from its Western counterparts.

Two themes strike me as central to Hornstra’s photographs: the desire to document the Russian government’s unflinching shut-lid stance on decades-long national poverty—a vision which has been supported since Gorbachev’s years of post-Perestroika openness and restructuring, which resulted in lines of empty grocery shelves resembling prison cells and stereotypical images in the press of “starving babushkas hawking single daffodils on empty Moscow subway platforms” as NPR’s Ella Taylor said of Robin Hessman’s excellent documentary My Perestroika—and the realization that with capitalism comes the advent of popular culture and the desire to assert individualism through conspicuous consumption, even among the poor. In that way, Hornstra’s photos stage an interesting moral bridge between the over-the-top budget of the Sochi Olympics and the kind of turn-of-the-century industrialization of America, which often overlooked the rural poor in favor of bolstering middle class sleeper suburbs, ports and resort towns and, of course, world class cities, which would become not only leaders in the industrial economy but also attractive tourist meccas on the world stage, a reflection perhaps of what Putin has in store for Sochi’s post-Olympic revitalization. Here van Bruggen’s texts and James Agee’s Let Us Praise Famous Men, the narrative that accompanies Walker Evans’ photographs of Southern sharecropping families during the Dustbowl and President Roosevelt’s “New Deal” (a proposal to assist the rural poor), share a certain overlap.

There is a kind of moral imperative in Hornstra’s Sochi Project which—like historians attempting to trace Native American genealogical lineage to a great migration across the Bering Strait via a glacier ice bridge from Asia—draws an almost physical bridge between the kind of conspicuous consumption which we saw heralded in American fashion, film and music of the 1980s & 90s, through hits like Madonna’s Material Girl, and the retrograde influx of these same emblems of culture in Russia today. I couldn’t help but recall the seductive power of my first acoustic hit of 90s alt rock when looking at Hornstra’s photo of Sasha, a young Moscow musician (and Kurt Cobain lookalike) who reflects in his statement, “Our band was super popular, but we stopped performing. The city council initiated a campaign against our scene because our music was allegedly Satanic.” In reading van Bruggen’s accompanying text, I was struck by the implicit flashback to the first time I stayed up all night in high school listening to Nirvana’s “All Apologies.” Sasha’s long-hair-don’t-care coif alone recalls a certain mix of Marilyn Manson and Steven Tyler’s full-lipped androgyny. It is almost as though these items of pop culture walked across a moral land bridge from West to East to create a new melding of cultures.

Moscow, Russia. 2007. Photography by Rob Hornstra, courtesy Flatland Gallery.

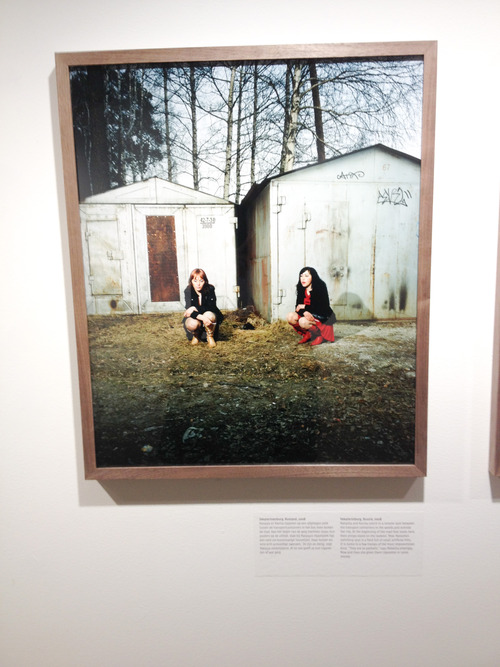

In Hornstra’s “Yekaterinburg, Russia 2008” young prostitutes Natasha and Kanita squat hunched between transport containers in a wooded area outside the city. The grungy fadeout of the postindustrial-meets-pastoral backdrop recalls today’s indie rock album art: in atmosphere, the photo resembles an album cover for Swedish female folk duo First Aid Kit. According to van Bruggen’s text on the accompanying placard, the girls’ pimp stands a ways off down the road to solicit travelers and passerby. “They are pathetic,” Natasha says of the older impoverished tramps who also make a home here. “Now and then she gives them money.”

Yekaterinburg, Russia 2008.

The young are not alone in capturing Hornstra’s lens. “Sochi Russia, 2009” features the aging, if graceful, body of Mikhail Pavelivich Karabelnikov in a royal blue Speedo and captain’s hat, standing astride a bright red life-saver. The image of the Sochi ocean at his back in the distance recalls a postcard of Coney Island. Van Bruggen’s accompanying text reads, “Every year Mikhail Pavelivich Karabelnikov travels three thousand kilometers from Novokuznetsk to take his vacation in Sochi. He was a miner for thirty-seven years and gradually worked his way up to foreman, in charge of some one hundred and fifty miners. His promising career came to an abrupt end when he refused to become a member of the Communist party, he says proudly.”

And then there is the stunningly composed portrait of a woman preparing fish in a cement factory canteen. “It is as if the moment the cement factory was finished in the 1950s, the ice age set in,” van Bruggen reflects on the photo. The woman recalls, “Our factory was the most beautiful in the Soviet Union’s industrial culture. We produced above capacity. It was a clean factory; there were six greenhouses where we grew roses which we distributed on Women’s Day. That’s no longer possible; we’re only allowed to make cement now. The factory was awarded the Order of Lenin twice. Then the Perestroika destroyed everything. We have lost eighteen years. The collective has fallen apart.”

Angarsk, Russia, 2008.

Beyond Hornstra’s portraits of stolid Russian individualism, we see him cast a wider angle toward the town of Sochi itself as a metaphor for the footprints of Russia’s ongoing industrialization and Putin’s vision of selective revitalization. The photos which comprise the Golden Years exhibition in total capture the visual story of a shifting Russian landscape—the ongoing changes in Russia’s geopolitical landscape reflected perhaps in the visual changes of the rugged places many call home. Gennadi Kuk, heralding from Krasnaya Polyna (of the Sochi region), reflects on the destruction of the local forest and valley in the text which accompanies his 2010 portrait: “My god, this still has to happen to me. It’s not that I’m against these Games. It’s the way it’s being done. The local authorities behave like spies, they never show their faces.”

Krasnaya Polyana, Sochi Region, Russia, 2010.

This narrative is reiterated in the landscape shots of Adler, a nearby coastal town and neighbor of Sochi. “Behind it rise the Sanatoria of Adler. Hotel rooms in Adler are marginally cheaper [than those in Sochi], which is immediately apparent on the beach. The permanent residents disdainfully call these tourists bzdykhs, a word unknown outside of Sochi. But anyone who has been to a beach resort will understand what it means: the overweight bodies sweating beer and spirits, the bare torsos and toes in sandals.” In contrast to Adler’s open working-class seascape, the portrait of Sochi stands like a magnetic sphinx rising from the sands. “Lenin’s palaces of the proletariat are slowly losing ground to the speculators and oligarchs.” “The closer the Games get, the faster the pace of construction and the flashier the commercials touting the expensive properties,” reads van Bruggen’s text.

Adler, Sochi Region, Russia, 2010.

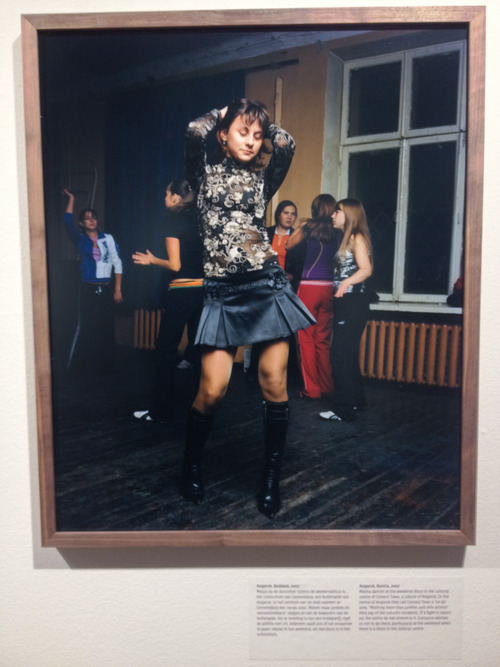

But perhaps most striking about the Golden Years show is the lingering feeling that this is not just a story of Sochi past or present, but of the Sochi(s) of the future. Ultimately, Hornstra’s Sochi Project offers a vivid coming of age tale, an observant if prognostic look at Russia’s youth and how they are coming to define their own aspirations amidst a shifting geopolitical lens. In “Angarsk, Russia, 2007” we see Marska dancing at the local disco in Cement Town, a suburb she describes as a “no-go area… nothing more than junkies and shiv artists.” In her stance we see a child on the verge of adulthood amidst a new Russian century, a doe-eyed future Russian cosmonaut perhaps, writhing her hips in her sateen mini-skirt and black knee-high boots in a way that hints at both her buoyant naiveté and her desire to encapsulate, and perhaps reproduce, a kind of Western-engineered image of youthful freedom engendered by the pop stars that people today’s MTV. I only wish I knew what song she was dancing to.

Angarsk, Russia, 2007.

However, it was the work of Olga Chernysheva which truly shined, a small installation called “Windows” (2007) which I passed by as I was leaving Golden Age. For Moscow-based video artist Olga Chernysheva, art is “a little office that conducts research into the poetic truth of life.”“Windows” offers a meditative, if somewhat somber, look at everyday life in contemporary Russia through a series of intimate installations composed of sixteen videos varying in length from 0:50–2:23 minutes, all installed in the traditional 4×6 frame within two sides of a blackened room, which resembles a darkened theatre. These mini-stages, resembling perhaps what Jeff Wall might have imagined of Joseph Cornell’s boxes had he been able to backlight them, flicker like mechanical eyelids, portals into the mundane and yet poetic world of everyday life. From across the room, each film is presented as a tiny illuminated window into some distant Soviet-era apartment building, not unlike the image, say, of driving down the West Side highway in the evening and observing the interminable rows of windows illuminated in the neatly stacked Riverside Homes that line the west side of Manhattan (I’ve often ironically thought this scene-scape resembled a series of rats in cages). One must approach each of Chernysheva’s films quite closely—pressing one’s nose to the glass of the “window”—to observe what trespasses inside each apartment she surveils. Here, Chernysheva offers a poetic glory hole into the heart of post-Perestroika Russian life. We see a woman ironing a short in her living room and a man playing guitar. In one we see the shaky outlines of a group of people—a family?—swaying and dancing as though in celebration. Something of Chernysheva’s shaky, sepia-tinged frames gives the impression of early silent 16mm film. It is as though a certain dust has gathered over the surface, making the subjects appear somewhat incandescent and grainy, as we scan the small, compact interior of these isolated apartments and the traces of the residual lives which inhabit and animate them.

It was, then, with great joy, as I was turning the corner of the Hamburger Bahnof Museum in Berlin that next week, that out of the corner of my eye I caught a glimpse of Olga Chernysheva’s other seminal video, “Train.” The show at the Bahnof in which Chernysheva’s “Train” was installed was called “The End of The 201th Century: The Best is Yet to Come.” Here, I thought, is no small coincidence. I have crossed countries and languages and cultural histories, and somehow I now find myself standing in once-Soviet-occupied East Berlin with all its post-unification scars and threadbare history, looking into the world of this Moscow-born artist once again, as though receiving a reminder of all the art yet to come from this country. “The Train” (2003), a single-channel video in which (as Ekaterina Andreeva observes in her staggering essay “Our Time According To Olga Chernysheva,”) “the human kaleidoscope transforms: the camera moves along the circuited space inside the carriages, along the passage from nowhere, into nowhere, along the mechanical ‘riverbed,’ which goes through rows of faces and bodies as though through a mass of water or earth which remains the same and changes every minute,” provides an elongated look at what it is to travel through Russia both physically and economically. As Ekaterina observes, “all of Chernysheva’s work is united by time and place: Central Russia, 2003-2004.” The film still I caught out of the corner of my eye featured the back of an elderly man, in what looked like an old oilcloth raincoat and hat, glimpsing through the train’s window the passing Russian landscape, which skirted an old white haired lady’s head, as he slowly walked down the train’s aisle. The caption in the subtitle read, “I live with natural simplicity. With philosophical enjoyment. And with the muse, so playful and young…” Chernysheva explains in the accompanying text, “The vast expanses of Russia make trains into more than means of transportation: instead, they become places of residence where singular forms of life unfold. […] the inhabitation of trains gains its inner form from the economics of beggary and traveling trade with cheap goods and from the aesthetics of wandering musicians and rhapsodic poets. The film’s ethical mood is underlined by the ‘timeless’ music of Mozart, which supplies the recognizable social texture of the image with an exalted well-temperedness, as if to tell the spectator: you don’t have to hurry, you have already reached where you wanted to go. For the duration of the journey, it is you who belong to this space and not it to you.” “For me,” Chernysheva reflects, “it’s about opening a new corner or a new atmosphere in Moscow. What is open already, but hidden.”

Perhaps it is with that same sentiment that one can approach the 2014 Winter Games. All the glory and glamour of the Games aside, perhaps this winter foray into a small seaside town on Russia’s rugged coast can offer not only a glimpse into the spectacle of sport, but a lens onto “what is open already, but hidden” of the Russian soul. As my mother, whose middle name is coincidentally also Olga and who grew up under the unflinching shadow of the Russian last name Dragon (or ˈdra-goon, as my Russian grandmother pronounced it), reflected after watching the opening ceremony, “Russia is about the power of the fine arts – classical music, dance and art. The arts elevate an entire people who worked (toiled) primarily with their hands in skilled and semi-skilled jobs under a communist regime with few freedoms. Yet, they have a deep and abiding appreciation and reverence for the classical works of Russian composers and artists who are among the most powerfully emotive and sustaining in the world—and who are considered “foreign” or “long-haired” to much of the world. Is it a time warp? I think not. The core of the Russian soul is rooted in a classical beauty which reflects their political struggles, their rugged land and climate and their ongoing history.” Or, as van Bruggen’s text reads, “Love is everywhere [in Russia], but you have to look for it.”

Kodori, Abkhazia, 2009.

Ann DeWitt’s writing has appeared in NOON, Guernica, BOMBlog, Esquire’s Napkin Fiction Project, The Believer Logger, art+culture, Everyday Genius, The Faster Times, elimae, and Dossier Magazine, amongst others, and is forthcoming in the anthology, Short: An International Anthology of 500 Years of Short-Short Stories, Prose Poems, Brief Essays, and Other Short Prose Forms, edited by Alan Ziegler due out in 2014. Ann holds a B.A. from Brown University and an M.F.A. in Fiction from Columbia School of the Arts. She was a Founding Editor of Gigantic: A Magazine of Short Prose and Art in 2008. She currently teaches in the Undergraduate Creative Writing Program at Columbia University and in The Art and Design History and Theory department at Parsons, The New School, and is at work on her first novel. For more of her work, please follow her blog at: http://talllikethreeapples.wordpress.com.