On Turkey’s Recent Twitter Ban

I discovered Twitter in 2007 when it became a news item on technology websites. I used to check those sites every morning like an obsessive bird watcher. I was writing the technology column at a Turkish newspaper and Twitter seemed like a story I could sell at the news meeting. After pitching it as the next big internet thing I realized—like many before me—that I had failed to answer questions about what exactly Twitter was. It was only two years later, while doing my military service in an Anatolian town filled with bird-song, that I learned Twitter had finally taken off in Turkey. Celebrities had made it their nest and fans followed. Journalists hid themselves behind avatar-shaped trees to listen to gossip, and found a lot of it. Turkey’s literati adapted to it, too, and the Turkish literary conversation began taking a new, twittery form.

In 2010, during a news meeting, I admitted to being a Twitter addict. A colleague said she wanted to pen an article about social media addiction and asked for volunteers who could help her. She created a team consisting of Facebook, Google, and Twitter addicts. She put us in a cab and brought us to a mental institution where we made a clean breast of our unhealthy fixation with our addictions.

I confessed that I couldn’t resist touching my timeline. Similar confessions were voiced from different corners of the clinic. In order to give an account of the severity of our addictions, we went onto a ten-day fast, and were only allowed to log onto our accounts after the issue hit the stand. The cover picture featured four of us standing in a police lineup. The headline read, “The Usual Addicts.”

I remembered that image two weeks ago when I found myself deprived of Twitter—only this time it was not because of an experiment, but a court order. When reports about the Twitter shutdown appeared on my timeline in the form of late-night tweets, I thought they were exaggerated. Checking a timeline late at night is an experience similar to visiting a bar after hours, and I found it strange to hear from fellow barflies that the bar was being locked down as we sat behind the counter. My initial reaction was disbelief. Twitter was a natural force, like the rain. It could not be stopped.

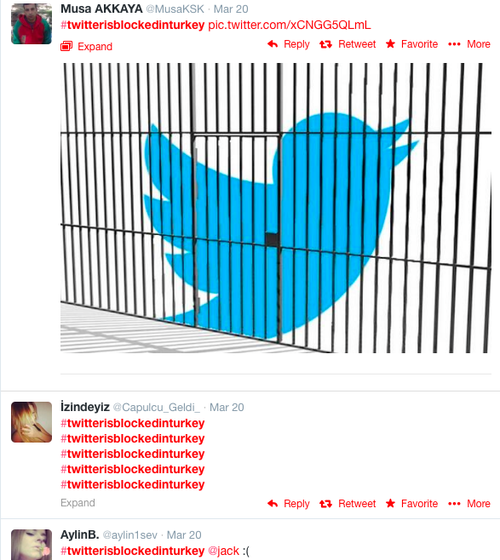

But it could, and was stopped when Turkish courts successfully captured the bird, put it in a cage and by morning, Twitter was, well, not dead but a bit flabbergasted. To hear it sing again, old addicts like me had to learn shortcuts. The easiest way to get around the ban was to change the DNS settings. Google’s public DNS, 8.8.8.8, became a magic formula and even showed up as graffiti in my neighborhood. Some joked about how their grandmothers managed to master the network settings of their computers. People, young and old, were back on Twitter.

This was merely the first round. The next morning a so-called IP block was imposed on the site and it became unreachable. For those who knew how to use a technology called VPN there was still an alternative way to reach the site, but I lost my patience and decided to find out whether the Twitter ban could in fact be a good thing for my intellectual life.

Maybe, I thought, it was God’s way of telling me that life without Twitter would bring happiness, satisfaction, and joy. I could even finish the Pierre Bourdieu tome that waited on my bookshelf from time immemorial.

* * *

Thus began my new life where Twitter was no longer a click away. I had to do with e-mail and literary websites, including this one. My first hours with this new regime were quite productive. I wrote a proposal for a university press for a book about the Turkish novel, polished my short story about a famous Turkish novelist, and read the Matthew Weiner interview in the new Paris Review. I visited a new fancy café in my neighborhood and went to the swimming pool, and enjoyed being underwater far, far away from the chirping of the opinionated and ostensibly wise, so much so that I wished Jack Dorsey had never invented Twitter.

When something is taken away from you, you continue to think about it, even obsess over it. When Twitter became a thing of the past I started to feel nostalgic and couldn’t help but think about old times.

As I sat alone in my living room, looking at the cover of Bourdieu’s book, I realized how the ban turned into a madeleine for my mind, and I remembered those distant days when we had frequent power cuts in Istanbul. Members of the household would meet in the living room to discuss what had just happened and what might happen next. Waiting for the lights to come back, I would see the beauty of life without electricity. As soon as it was gone, technology would reveal its true nature to me. I could see that it was a force that divided rather than brought people together, it was a tool of selfishness, and when its deceptive cover lifted, everything would reveal itself in all of its meaninglessness.

My week without Twitter could bring me to a similar moment of truth. I could enter the postmodern Platonic cave, located in San Francisco, and have a look at forms whose shadows I had seen all my life without seeing the ideas behind them. Now I could see that the man who looked so cool on my timeline with his Morrissey video posts and quotes from T.S. Eliot was in fact a douchebag who had nothing original to say about music or poetry. I was deaf but now I could hear.

On my third day without Twitter, however, I realized that I couldn’t say about Twitter what Sartre had said about hell. It was not other people. It was me. Twitter had done things to me that I couldn’t undo. It had imposed a regime of reading onto my mind. It had opened my ears to a particular mode of conversation. It had reminded me that I was not alone as a reader, and that I could share my reading with others whenever I wanted. Twitter had created in my brain the idea of an implied reader who I should consider whenever I wrote a new sentence.

In other words, despite seeming like a good thing in the beginning, Twitter’s disappearance from my life quickly felt like solitary confinement. I became part of a group of people who were specifically targeted and denied access to people outside them. Although my reading became more focused my ability to share them with others disappeared. I had more things to say, thanks to the time I gained from the destruction of my timeline, but the people I could say them to no longer existed.

I was aware that I had been moved out of a room I once inhabited, the geography of which I well knew. I began to miss Evan Kindley’s morning tweets, Christian Lorentzen’s aphorisms, and Roxane Gay’s reports from literary gatherings in American states where I had never been. I realized how I had taken the existence of my fellow Turkish twitter friends for granted.

A day after the Twitter ban I managed to reach the mobile version of Twitter from my university campus and saw a mention by the editor of Index on Censorship, a British magazine famous for its decades long advocacy for freedom of expression. The editor wrote: “Earth to @kayagenc can you hear us? #Turkey”. This note of concern from a colleague, lucky enough still to inhabit the Twitter salon, increased my awareness of being outside it.

By the end of that week I had still not cracked the cover of Bourdieu’s book. But I found a way to connect to Twitter. When things returned to normal and Turkey lifted the ban on April 3, I started reading La Distinction. The real feat would be to read itdespite the continued distraction of other people’s voices, the value of which one learns to appreciate better after experiencing censorship like we did.

Kaya Genç is a novelist and essayist from Istanbul. His work has appeared in the Paris Review Daily, the Guardian, the Financial Times, the London Review of Books blog, Salon, and Guernica Magazine, among others. L’Avventura (Macera), his first novel, was published in 2008. Kaya is the Istanbul correspondent of the Los Angeles Review of Books and is currently working on his third novel. He blogs at www.kayagenc.net and tweets @kayagenc.