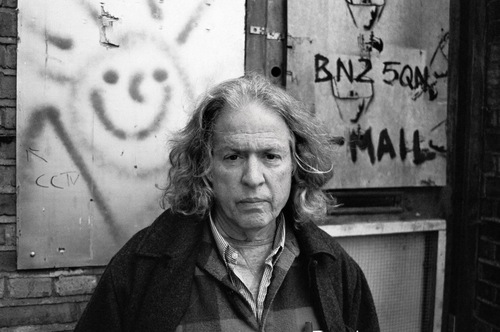

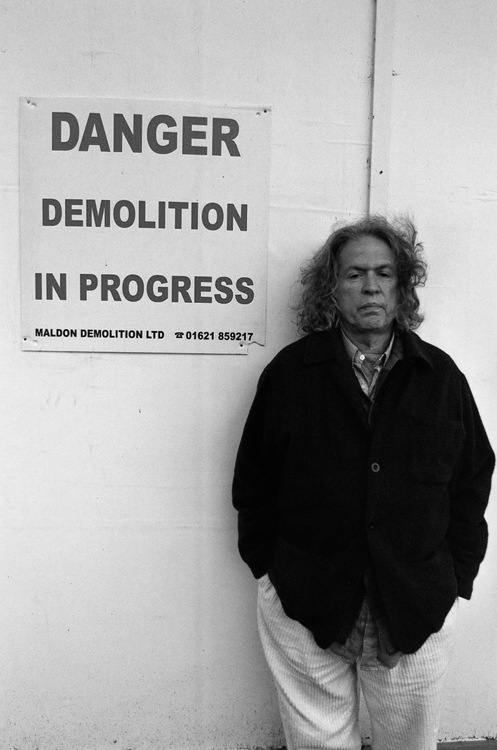

Photograph by Mark Mawston

An Interview with Stephen John Kalinich

Stephen John Kalinich is a prolific poet and songwriter who wears eye catching hats and the color orange on an almost daily basis. He is warm and nurturing to almost everyone in his life, including people he meets in restaurants and on the street. He is also an amazing friend, and it so happens that his friends, Brian and Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys, were also his collaborators. It is not coincidental that two of the songs he wrote with Dennis, “LittleBird” and “Be Still”, are featured on The Beach Boys’ 1969 album, Friends. Kalinich has written for Paul McCartney, Randy Crawford, Mary Wilson, and is currently working with legendary Nashville musician/producer Jon Tiven (who’s worked previously with Alex Chilton, Frank Black, Don Covay) under the name Yo MaMa. They put out the gloriously primitive Stones-meets-Stooges opus Symptomology, which Andrew Loog Oldham lauded as one of the best albums of 2012. A practitioner of Transcendental Meditation for many years, Stevie has also contributed to David Lynch’s Transcendental Radio.

Light in the Attic Records will be releasing Stevie’s 1968 collaboration with Brian Wilson, A World of Peace Must Comeon vinyl this April. There’s been much speculation on the genesis of this project, and for many years people wondered if it was real at all. Stevie and I sat down in my living room to talk about his beginnings and to sort out the mysteries of A World of Peace Must Come.

—Tracy Landecker

I. GANGSTER CHILD POET

STEVIE KALINICH: My mother, every Sunday, would take us for walks in nature in Binghamton, New York, in the hills above where we lived. There was a lot of wilderness, and we walked around creeks. There were bulls behind fences, and my mother would say, “Don’t go in there. “ We would find skeletons. Once we found what we thought was the skeleton of a dead baby in a creek. We loved all the different colors of the leaves. We used to go tobogganing on the hill that had trees, and one time I went head first into a tree and I don’t know if I ever recovered. [Laughs]

I had this sense of walks in nature but I don’t think I felt it as anything other than how life was. But as I look back, that’s when my first poems started coming. I didn’t know what they were. I was five, six, seven years old. They weren’t very good, but I remember one of them and I’ve spoken it before.

At night I saw the stars above

A sign of hope and peace and love

The stars that shine above my eyes

That make me know

God is in the skies

THE BELIEVER: And these poems were the seeds that you tilled, as it were, for A World of Peace Must Come.

SK: Yes. But at that point as a child, whatever concept I had of God, which was very vague, was of something out there, outside of myself. As I’ve grown, I don’t think I would change that poem, except I would say that what I thought was out there is within consciousness, rather than outside of it. But we all project our beliefs and our systems.

BLVR: Was your mom creative and artistic?

SK: My mom was brilliant. She had a nervous breakdown when she was younger, she had such a high I.Q. They pulled her out of school for a while, but she never came back to her full sources.

BLVR: Did she expose you to books or poetry? Was that something you did on your own?

SK: I think I got exposed more to hanging out with older people, who would teach me how to drink, smoke, hold a cigarette in my mouth while they shot a BB gun. I was the fearless one, but I was scared. I wouldn’t show it. So I got exposed to all the stuff you would see in David Lynch movies, I was the poster child for that.

BLVR: So you hung with a colorful crowd.

SK: I lived with my grandparents a lot because my mother couldn’t handle me. I was not a great student. I always wanted attention. I would throw spitballs in class and I don’t think I was exceptionally artistic as a child. I wasn’t very good at English or punctuation, but I had a feeling, so I started writing those little poems. When I got older, I felt like I was in the presence of something so magnificent that would take me over when I wrote.

BLVR: How old?

SK: Maybe under thirteen: “I am waiting for tomorrow and in it hope to find the meaning of my life/I once knew what a child feels and hopes what it means to be born/I am waiting for you mysterious darkness/a noble secret”.

BLVR: How much of the bad crap in your childhood (because we all have bad crap, nobody gets out of here unscathed) informed you in thinking about these kinds of huge existential questions as a child?

SK: I’ll tell you when it started. I was four years old. I was sitting on the bed in Binghamton, New York. Here I was in this winter, in this house, sitting on the bed, but nothing was real. I was weightless. I was floating, there didn’t seem to be any reality to existence. And my mother said, “You would go to a place. You were unreachable.” Is that mental?

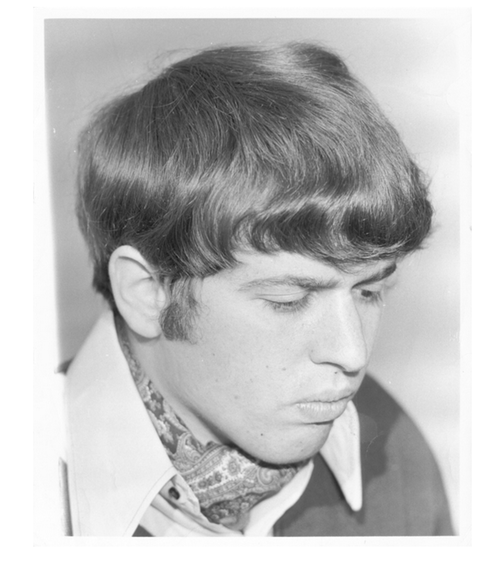

BLVR: No. I would call that dissociating. This is the gift of having a hard time as a kid: you accelerate in certain areas. I’ve seen the pictures of you as a kid and you were a little badass. How old were you in that picture you showed me?

SK: Second grade. Maybe seven. They said I was the second or third toughest in my school. If I tackled someone I wouldn’t let go. I thought I’d be willing to take a punch. I didn’t realize it could kill me then. I was fearless because I was trying to prove that, because I was short and small, I could stand up to anyone and wouldn’t back down. By the time I was fifteen I changed.

BLVR: What happened when you were fifteen?

SK: I was reading these books that said it takes moral courage to back down. So when someone tried to confront me at the pool hall at the YMCA, I wouldn’t fight him. They were calling me coward and chicken and all this stuff, and I wouldn’t do it. I went away with little tears in my eyes but I didn’t fight. I became a peace activist.

II. POTENTIAL

BLVR: One of the songs on A World of Peace is “America I Love You,” which is a very beautiful depiction of the country. It’s sort of how I felt about it when I was a kid before I read books and went to college and was like, “holy shit, this is a freak show.”

SK: The song is based on when I was nineteen, after my father passed. I wanted to hitchhike across the country. I baled hay, slept in jails, sailed boats on Lake Granada, and I bodysurfed on the Pacific. I carved my name in the sand. I fell in love and got married.

BLVR: So you did all the things you list in the song?

SK: Yes. I had notebooks, journals, recitations. I had the name of each person who picked me up. They were all in a suitcase that was lost. I try to recollect it. I get glimpses.

BLVR: You hung out with a colorful crowd when you lived in Binghamton, then you hung out with a colorful crowd when you moved to Los Angeles. Why did you originally come to LA?

SK: I came here originally to be an actor. I thought I could be an intense character actor, like Marlon Brando. I studied with Lawrence Parks in Hollywood. I discovered I was a poet and a songwriter in my pursuit of acting. I met Renee, my ex-wife. We’re still friends. I over-romanticized things like a poet would do. For the first 150 weeks after we got together, I would write her a love letter, at least once a week. A while there it was once a day.

BLVR: How did you meet Renee?

SK: Through some weird people in Hollywood.

BLVR: You knew some weird people in Hollywood?

SK: Yeah, I got exposed to gypsy boots, all the health fanatics, and the new age movement, very young. But the thing is that is interesting is that I thought I created that, because when I started writing those poems you like, I’d never heard of anything, I was doing them alone.

BLVR: You were kind of a new age pioneer.

SK: I never knew any of it existed. “Magic Hand,” and all that stuff you like on the album, “If You Knew,”—that was all before I knew of any movements like Unity or spiritualism. I didn’t know any of that. I started writing, so the gift came from the source, or whatever it is.

BLVR: I think it was innate. So how did you get signed with the Beach Boys?

SK: I moved into the Hollywood Y and I met this guy Mark Lyndsay Buckingham, but not the one from Fleetwood Mac. I wrote songs and he did music. He was a great twelve-string guitar player, so we did my song “Leaves of Grass.” And Carl Wilson produced it. So the first one to produce me was Carl Wilson.

Brian was rehearsing at The Smothers Brothers Theater, working with an R&B group. Carl had me in the room, and I recited “The Magic Hand “and “If You Knew.” He was blown away and they wanted to sign me. I wasn’t a great singer, but Carl taught me, “Stephen, don’t punch it, speak it and add volume.” Because when you punch it you lose the melody. You can get that psychedelic effect. So Carl taught me that a person with no voice could become a singer.

BLVR: Did Brian help you with the formulation of the songs?

SK: No, I did all of them. He did the background music when I was reciting. The essence of the songs was that love was everything. Even in “Lonely Man”: “The flower and the meadow, the orchard, the cherry tree, the love was there, everywhere, the love we did not see.” So mankind doesn’t see the potential love within us. Which is akin to a lot of things. I thought I could do what the Beatles did as a poet.

I would visualize myself (I know this sounds crazy) on Ed Sullivan. I thought that I was going to be “the poet”. You know how the Rolling Stones did “My Sweet Lady Jane?” I’d come in with the long flowing coat, capes and stuff.

BLVR: And recite on Ed Sullivan.

SK: All over. All over the world. The Beach Boys even booked me in the sixties to open the tour with the Maharishi, it was all coming true. And then that tour bombed. Luckily, I had cancelled because wife was sick, and I didn’t go. Then Brian and I worked on the album.

BLVR: This was when Brian was having a hard time, was it not? Maybe he saw something in you that he needed. Some kind of a spiritual anchoring that may have been lacking. Maybe Dennis saw that in you as well. Some are of the mind that Dennis was extremely influenced by you.

SK: I think in one interview Dennis or Al Jardine said I was a catalyst for the Beach Boys. I was the one who opened up Dennis’ writing.

III. A SOBERING UP

BLVR: A World of Peace has a very eerie sound. Someone compared this album to Nico’s The Marble Index. The comparison is actually so apt. It’s just her and her poetry. I think the similarity is not so much in the content as the mood. There is a gravity to the mood of the whole thing, to your album and to hers. But Nico is her own universe. Just like this album is, to me, its own universe. It does not follow a lot of standard rules.

SK: It follows no rules.

BLVR: So it’s kind of uncategorizable. It’s unique, it’s haunting, it’s moving.

SK: I probably couldn’t even capture it again.

BLVR: Well, there is this life force that comes out of you when you recite. A mixture of love, awe, sadness, and a little anger.

SK: It’s a sobering up. It fucking hits you in the gut. The point was that God is not coming out of the sky. Man, where he is, in his nakedness, must make this world better or worse. It’s not going to come down on a magic carpet. And this kind of thinking leads to a lot of problems—this kind of utopian thinking. It’s the opposite of Utopianism. It’s the sense of taking responsibility for the planet or yourself on a moment-to-moment basis.

BLVR: So the thing is the kind of love you’re talking about is very strong, very powerful. It’s not hippy dippy.

SK: And it stands up to the enemy.

BLVR: It’s tough.

SK: It’s so powerful that everything goes down before it. It’s fearless in the sense that it goes through death. This is how I feel.

BLVR: And this was the concept you had in your twenties?

SK: I had it in my teens.

BLVR: When World of Peace was made, there was the assassination of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. The darkness is taking over in the U.S., big time, not that it wasn’t always there, it’s just coming to the surface.

SK: World of Peace is a product of its time, but it’s also a product of this time.

BLVR: Well, absolutely. We’re in another dark time. We’re at another turning point. Where did you record?

SK: We recorded at Ocean Way, Brian’s house, Wally Heider’s, a lot of different studios. The common myth is that we recorded it one night at Brian’s house, but it took months and months. Each track was different. The thing that’s important about Brian: With the “America I Love You” track there was an orchestra with a lot of the Wrecking Crew playing on it, Tommy Morgan and a few others. Brian directed them and let them improvise based on the theme he was looking for. And after that he said, “No, Stevie, let’s keep it the way you did it for me, let’s make it like a home recording.” Very simple.

BLVR: And that was a conscious aesthetic choice.

SK: Yes. On “The Magic Hand,” Brian got the idea to have all of his wife’s girlfriends come into the studio and sing. It’s a little off key. It’s got that real authenticity. But each track was thought out. Once he had me call him. He had the receiver next to the mic and we’d sing through it, so the mic would record me from the other room. Some of those didn’t make it on the album. Or he’d have the dogs barking. And there was water on some of the tracks. So it was very experimental. For one track, Brian put me in the shower and put the mic over it. But the recording is as psychedelic as anything on Smile, maybe more so. It really captures that era, and I think that’s why it holds up. And that’s why Light in the Attic got interested. It’s not really dated, or at least I don’t feel it is.

I thought that putting it out there would be easier at the time. Going to the peace rallies—I never really felt a total part of that. And P.F. Sloan was my partner. I thought the world situation and people were darker than what was portrayed. Darker than some of the protest songs. I thought they were sentimental.

IV. A FRIEND LIKE YOU

BLVR: You co-wrote a duet for Brian Wilson and Paul McCartney. You wrote the words and Brian the melody. Tell me about that and a little about your long friendship with Brian.

SK: It wasn’t until the 2000s that I wrote for McCartney, but the seed was planted forty years before. My relationship with Brian was intense. Later in life we would have breakfast, lunch, and dinner every day. We would get together. Maybe the duet wasn’t just for McCartney. Maybe it was about my friendship with Brian, maybe God: “You have courage, you have risked it all/you pick me up and every time I fall/you inspire me every day of my life/a friend like you.” Some people thought that was sappy and square but what was happening was the reception of the message that we all need friends like this. The world needs a more sincere and genuine message, not total cynicism. Not total darkness, even though there are times where I feel dark, and you know from the things you’ve seen me write that I have both sides.

BLVR: But you’re not cynical. You’ve never, ever been cynical, which is interesting.

SK: I still have hope, and the experiment is myself. If I can get through the illness and pain and still find joy then it’s possible for others. Even if I am dying, I have to accept and know there are options. Like, how do I face it? Do I have to be miserable? That’s what I like about Matisse, making the cutouts in the chair. That’s beautiful, to me. Doing that instead of caving into his illness. So that’s what I try to do. I am diabetic. I try to use it in creative ways. I’m not saying I don’t complain, because I do.

BLVR: Well, that’s human.

SK: I try to go beyond it.

See more info about the rerelease of A World of Peace Must Come.