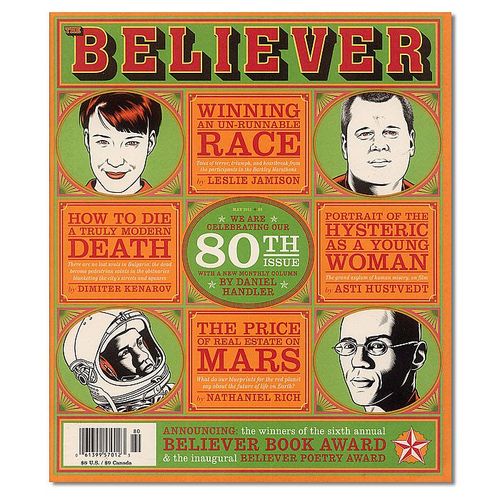

To celebrate the upcoming collected stories concert series curated by David Lang at Carnegie Hall (April 22-29), we’ll be posting pieces from past issues of the Believer that tie into with the themes of each show. The fourth concert in collected stories is Travel, featuring a performance of Liszt’s Années de pèlerinage by pianist Louis Lortie, for which we’re posting Leslie Jamison’s essay on the Barkley Marathons (from the May 2011 issue of the Believer).

THIRTY-FIVE RUNNERS FACE HOLLERS AND HELLS, A FLOODED PRISON, RATS THE SIZE OF POSSUMS, AND FLESH-FLAYING BRIARS TO TEST THE LIMITS OF SELF-SUFFICIENCY.

DISCUSSED: An Escaped Assassin, Raw Chicken Meat, Unimaginable Physical Exhaustion, A License Plate from Liberia, Duct-Tape Pants, Novels Hidden in Tree Trunks, Testosterone Spread Like Fertilizer, Rattlesnakes as Large as Arms, Arms That Baptize Cats, A Bunch of Guys in the Woods Talking about Something Called the Bad Thing

On the western edge of Frozen Head State Park, just before dawn, a man in a rust brown trench coat blows a giant conch shell. Runners stir in their tents. They fill their water pouches. They tape their blisters. They eat thousand-calorie breakfasts: Pop-Tarts and candy bars and geriatric energy drinks. Some of them pray. Others ready their fanny packs. The man in the trench coat sits in an ergonomic lawn chair beside a famous yellow gate, holding a cigarette. He calls the two-minute warning.

The runners gather in front of him, stretching. They are about to travel more than a hundred miles through the wilderness—if they are strong and lucky enough to make it that far, which they probably aren’t. They wait anxiously. We, the watchers, wait anxiously. A pale wash of light is barely visible in the sky. Next to me, a skinny girl holds a skinny dog. She has come all the way from Iowa to watch her father disappear into this gray dawn.

All eyes are on the man in the trench coat. At precisely 7:12, he rises from his lawn chair and lights his cigarette. Once the tip glows red, the race known as the Barkley Marathons has begun.

I.

The first race was a prison break. On June 10, 1977, James Earl Ray, the man who shot Martin Luther King Jr., escaped from Brushy Mountain State Penitentiary and fled across the briar-bearded hills of northern Tennessee. Fifty-four hours later he was found. He’d gone about eight miles. Some might hear this and wonder how he managed to squander his escape. One man heard this and thought: I need to see that terrain!

Over twenty years later, that man, the man in the trench coat—Gary Cantrell by birth, self-dubbed Lazarus Lake—has turned this terrain into the stage for a legendary ritual: the Barkley Marathons, held yearly (traditionally on Lazarus Friday or April Fool’s Day) outside Wartburg, Tennessee. Lake (known as Laz) calls it “The Race That Eats Its Young.” The runners’ bibs say something different each year: SUFFERING WITHOUT A POINT; NOT ALL PAIN IS GAIN. Only eight men have ever finished. The event is considered extreme even by those who specialize in extremity.

II.

What makes it so bad? No trail, for one. A cumulative elevation gain that’s nearly twice the height of Everest. Native flora called saw briars that can turn a man’s legs to raw meat in meters. The tough hills have names like Rat Jaw, Little Hell, Big Hell, Testicle Spectacle—this last so-called because it inspires most runners to make the sign of the cross (crotch to eyeglasses, shoulder to shoulder)—not to mention Stallion Mountain, Bird Mountain, Coffin Springs, Zip Line, and an uphill stretch, new this year, known simply as “the Bad Thing.”

The race consists of five loops on a course that’s been officially listed at twenty miles, but is probably more like twenty-six. The moral of this slanted truth is that standard metrics are irrelevant. The moral of a lot of Barkley’s slanted truths is that standard metrics are irrelevant. The laws of physics and human tolerance have been replaced by Laz’s personal whims. Even if the race was really “only” a hundred miles, these would still be “Barkley miles.” Guys who could typically finish a hundred miles in twenty hours might not finish a single loop here. If you finish three, you’ve completed what’s known as the Fun Run. If you happen not to finish—and, let’s face it, you probably won’t—Laz will play taps to commemorate your quitting. The whole camp, shifting and dirty and tired, will listen, except for those who are asleep or too weak to notice, who won’t.

III.

It’s no easy feat to get here. There are no published entry requirements or procedures. It helps to know someone. Admissions are decided by Laz’s personal discretion, and his application isn’t exactly standard, with questions like “What is your favorite parasite?” and a required essay with the subject “Why I Should Be Allowed to Run In the Barkley.” Only thirty-five entrants are admitted. This year, one of them is my brother.

Julian is a “virgin,” one of fifteen newbies who will do their damndest to finish a loop. He has managed to escape the designation of “sacrificial virgin,” officially applied to the virgin each year (usually the least experienced ultra-runner) whom Laz has deemed most likely to fail in a spectacular fashion—to get lost for so long, perhaps, that he manages to beat Dan Baglione’s course record for slowest pace. At the age of seventy-five, in 2006, Baglione managed two miles in thirty-two hours. Something to do with an unscrewed flashlight cap, an unexpected creek.

It’s probably a misnomer to talk about “getting lost” at Barkley. It might be closer to the truth to say you begin lost, remain lost through several nights in the woods, and must constantly use your compass, map, instructions, fellow runners, and remaining shards of sanity to perpetually unlose yourself again. First-timers usually try to stay with veterans who know the course, but are often scraped. “Virgin scraping” means ditching the new guy. A virgin bends down to tie his shoelaces, perhaps, and glances up to find his veteran Virgil gone.

IV.

The day before the race, runners start arriving at camp like rainbow seals, sleekly gliding through the air in multi-colored bodysuits. They come in pickup trucks and rental cars, rusty vans and camper trailers. Their license plates say 100 RUNNR, ULT MAN, CRZY RUN. They bring camouflage tents and orange hunting vests and skeptical girlfriends and acclimated wives and tiny travel towels and tiny dogs. Laz himself brings a little dog (named “Little Dog”) with a black spot like a pirate’s patch over one eye. Little Dog almost loses her name this year, after encountering and trying to eat an even smaller dog, the skinny one from Iowa, who turns out to be two dogs rather than just one.

It’s a male scene. There are a few female regulars, I learn, but they rarely manage more than a loop. Most of the women in sight, like me, are part of someone’s support crew. I help sort Julian’s supplies in the back of the car.

He needs a compass. He needs pain pills and NO-DOZ pills and electrolyte pills and Ginger Chews for when he gets sleepy and a “kit” for popping blisters that basically includes a needle and Band-Aids. He needs tape for when his toenails start falling off. He needs batteries. We pay special attention to the batteries. Running out of batteries is the must-avoid-at-all-costs worst possible thing that could happen. But it has happened. It happened to Rich Limacher, whose night spent under a huge buckeye tree earned it the name “Limacher Hilton.” Julian’s coup de grâce is a pair of duct-tape pants that we’ve fashioned in the manner of cowboy chaps. They will fend off saw briars, is the idea, and earn Julian the envy of the other runners.

Traditionally, the epicenter of camp is a chicken fire kindled on the afternoon before the race begins. This year’s fire is blazing by four p.m. It’s manned by someone named Doc Joe. Julian tells me Doc Joe’s been wait-listed for several years and (Julian speculates) has offered himself as a helper in order to secure a spot for 2011. We arrive just as he’s spearing the first thighs from the grill. He’s got a two-foot can of beans in the fire pit, already bubbling, but the clear stars of this show are the birds, skin-blackened and smothered in red sauce. The chicken here (as legend has it) is served partway thawed, with only skins and “a bit more” cooked.

I ask Doc Joe how he plans to find the sweet spot between cooked and frozen. He looks at me like I’m stupid. That frozen chicken thing is just a myth, he says. This will not be the last time, I suspect, that I catch Barkley at the game of crafting its own legend.

At this particular potluck, small talk rarely stays banal for long. I fall into conversation with John Price, a bearded veteran who tells me he’s sitting out the race this year, wait-listed, but has driven hundreds of miles just to be “a part of the action.” Our conversation starts predictably. He asks where I’m from. I say Los Angeles. He says he loves Venice Beach. I say I love Venice Beach, too. Then he says: “Next fall I’m running from Venice Beach to Virginia Beach to celebrate my retirement.”

I’ve learned not to pause at this kind of declaration. I’ve learned to proceed to practical questions. I ask, “Where will you sleep?”

“Mainly camping,” he says. “A few motels.”

“You’ll carry the tent in a backpack?”

“God, no,” he laughs. “I’ll be pulling a small cart harnessed to my waist.”

I find myself at the picnic table, which has become a veritable bulimic’s buffet, spread with store-bought cakes and sprinkle cookies and brownies. It’s designed to feed men who will do little for the next few days besides burn an incredible number of calories.

The tall man next to me is tearing into a massive chicken thigh. His third, I’ve noticed. Its steam rises softly into the twilight.

“So that whole frozen thing?” I ask him. “It’s really just a myth?”

“It was one year,” he says. “It was honest-to-god frozen.” He pauses. “Man! That year was a great race.”

This guy introduces himself as Carl. Broad and good-looking, he’s a bit less sinewy than many of his fellow runners. He tells me he runs a machine shop down in Atlanta. As best I can gather, this means he uses his machines to build other machines, or else he uses his machines to build things that aren’t machines—like bicycle parts or flyswatters. He works on commission. “The people who ask for crazy inventions,” he says, sighing, “are never the ones who can afford them.”

Carl tells me that he’s got an ax to grind this time around. He’s got a strong history at Barkley—one of the few runners who has finished a Fun Run under official time—but his performance last year was dismal. “I barely left camp,” he says. Trans-lated, this means he ran only thirty-five miles. But it was genuinely disappointing: he didn’t even finish a second loop. He tells me he was dead-tired and heartbroken. He’d just gone through a nasty breakup.

But now he’s back. He looks pumped. I ask him who he thinks the major contenders are to complete a hundred.

“Well,” he says, “there’s always Blake and A.T.”

He means two of the “alumni” (former finishers) who are running this year: Blake Wood, class of 2001, and “A.T.”, Andrew Thompson, class of 2009. Finishing the hundred twice would make history. Two years in a row is the stuff of fantasy.

Blake is a nuclear engineer at Los Alamos with a doctorate from Berkeley and an incredible Barkley record: six for six Fun Run completions, one finish, another near finish that was blocked only by a flooded creek. In person, he’s just a friendly middle-aged dad with a salt-and-pepper mustache, eager to talk about his daughter’s bid to qualify for the Olympic Marathon Trials, and about the new pair of checkered clown pants he’ll wear this year to boost his spirits on the trail.

Andrew Thompson is a youngish guy from New Hampshire famous for a near finish in 2005, when he was strong heading into his fifth loop but literally lost his mind when he was out there—battered from fifty hours of sleep deprivation and physical strain. He completely forgot about the race. He spent an hour squishing mud in his shoes. He came back four more times until he finally finished the thing, in 2009.

There’s “J.B.”, Jonathan Basham, A.T.’s best support crew for years, at Barkley for his own race this time around. He’s a strong runner, though I mainly hear him mentioned in the context of his relationship to A.T., who calls him “Jonboy.”

Though Carl doesn’t say it, I learn from others that he’s a strong contender, too. He’s one of the toughest runners in the pack, a D.N.F. (Did Not Finish) veteran hungry for a win. I picture him out there on the trails, a mud-splattered machinist, with mechanical claws picking granola bars from his pockets and bringing them to his mouth.

There are some strong virgins in the pack, including Charlie Engle, already an accomplished ultra-runner (he’s “done” the Sahara) and inspirational speaker. Like many ultra-runners, he’s a former addict. He’s been sober for nearly twenty years, and many describe his recovery as the switch from one addiction to another—drugs for adrenaline, trading that extreme for this one.

If there’s such a thing as the opposite of a virgin, it’s probably John DeWalt. He’s an old man in a black ski cap, seventy-three and wrinkled, with a gruff voice that sounds like it should belong to a smoker or a cartoon grizzly bear. He tells me that his nine-year-old grandson recently beat him in a 5K. Later, I will hear him described as an animal. He’s been running the race for twenty years—never managing a finish or even a Fun Run.

I watch Laz from across the campfire. He’s darkly regal in his trench coat, warming his hands over the flames. I want to meet him, but haven’t yet summoned the courage to introduce myself. When I look at him I can’t help thinking of Heart of Darkness. Like Kurtz, Laz is bald and charismatic, leader of a minor empire, trafficker in human pain. He’s like a cross between the Colonel and your grandpa. There’s certainly an Inner Station splendor to his orchestration of this whole hormone extravaganza, testosterone spread like fertilizer across miles of barren and brambled wilderness.

He speaks to “his runners” with comfort and fondness, as if they are a batch of wayward sons turned feral each year at the flick of his lighter. Most have been running “for him” (their phrase) for years. All of them bring offerings. Everyone pays a $1.60 entry fee. Alumni bring Laz a pack of his favorite cigarettes (Camel Filters), veterans bring a new pair of socks, and virgins are responsible for a license plate. These license plates hang like laundry at the edge of camp, a wall of clattering metal flaps. Julian has brought one from Liberia, where—in his non-superhero incarnation as a development economist—he is working on a microfinance project. I asked him how one manages to procure a spare license plate in Liberia. He tells me he asked a guy on the street and the guy said, “Ten dollars,” and Julian gave him five and then it appeared. Laz immediately strings it in a place of honor, near the center, and I can tell Julian is pleased.

All through the potluck, runners pore over their instructions, five single-spaced pages that tell them “exactly where to go”—though every single runner, even those who’ve run the course for years, will probably get lost at least once, many of them for hours at a time. It’s hard for me to understand this—can’t you just do what they say?—until I look at the instructions themselves. They range from surprising (“the coal pond beavers have been very active this year, be careful not to fall on one of the sharpened stumps they have left”) to self-evident (“all you have to do is keep choosing the steepest path up the mountain”). But the instructions tend to cite landmarks like “the ridge” or “the rock” that seem less than useful, considering. And then there’s the issue of the night.

The official Barkley requirements read like a treasure hunt: there are ten books placed at various points along the course, and runners are responsible for ripping out the pages that match their race number. Laz is playful in his book choices: The Most Dangerous Game, Death by Misadventure, A Time to Die—evenHeart of Darkness, a choice that seems to vindicate my associative impulses.

The big talk this year is about Laz’s latest addition to the course: a quarter-mile cement tunnel that runs directly under the grounds of the old penitentiary. There’s a drop through a narrow concrete shaft to get in, a fifteen-foot climb to get out, and “plenty of” standing water once you’re inside. There are also, rumor has it, rats the size of possums and—when it gets warmer—snakes the size of arms. Whose arms? I wonder. Most of the guys here are pretty wiry.

The seventh course book has been hung between two poles next to the old penitentiary walls. “This is almost exactly the same place James Earl Ray went over,” the instructions say. “Thanks a lot, James.”

Thanks a lot, James—for getting all this business started.

V.

Laz has given himself the freedom to start the race whenever he wants. He announces the date but offers only two guarantees: that it will begin “sometime” between midnight and noon (thanks a lot, Laz), and that he will blow the conch shell an hour beforehand in warning. In general, Laz likes to start before dawn.

At the start gate, Julian is wearing a light silver jacket, a pale gray skullcap, and his homemade duct-tape chaps. He looks like a robot. He disappears uphill in a flurry of camera flashes.

Immediately after the runners take off, Doc Joe and I start grilling waffles. Laz strolls over with his glowing cigarette, its gray cap of untapped ash quaking between his thick fingers. I introduce myself. He introduces himself. He asks us if we think anyone has noticed that he’s not actually smoking. “I can’t this year,” he explains, “because of my leg.” He has just had surgery on an artery and his circulation isn’t good. Despite this he will set up a lawn chair by the finish line, just like every year, and stay awake until every competitor has either dropped or finished. Dropping, unless you drop at the single point accessible by trail, involves a three-to-four-hour commute back into camp—longer at night, especially if you get lost. Which effectively means that the act of ceasing to compete in the Barkley race is comparable to running an entire marathon.

I tell him the cigarette looks great as an accessory. Doc Joe tells him that he’s safe up to a couple packs. Doc Joe, by the way, really is a doctor.

“Well, then,” Laz says, smiling. “Guess I’ll smoke the last quarter of this one.”

He finishes the cigarette and then tosses it into our cooking fire, where it smokes right into our breakfast. I am aware that Laz has already been turned into a myth, and that I will probably become another one of his mythmakers. Various tropes of masculinity are at play in Laz’s persona—badass, teenager, father, demon, warden—and this Rubik’s cube of testosterone seems to be what Barkley’s all about.

I realize Laz and I will have many hours to spend in each other’s company. The runners are out on their loops anywhere from eight to thirty-two hours. Between loops, if they’re continuing, they stop at camp for a few moments of food and rest. This is both succor and sadism; the oasis offers respite and temptation at once. It’s the Lotus Eaters’ dilemma: hard to leave a good thing behind.

I use these hours without the runners to ask Laz everything I can about the race. I start with the start: how does he choose the time? He laughs uneasily. I backtrack, apologizing: would it ruin the mystery to tell me?

“One time I started at three,” he says, as if in answer. “That was fun.”

“Last year you started at noon, right? I heard the runners got a little restless.”

“Sure did.” He shakes his head, smiling at the memory. “Folks were just standing around getting antsy.”

“Was it fun to watch them agonize?” I ask.

“Little bit frightening, actually,” he says. “Like watching a mob turn ugly.”

As we speak, he mentions sections of the course—Danger Dave’s Climbing Wall, Raw Dog Falls, Pussy Ridge—as if I’d know them by heart. I ask whether Rat Jaw is called that because the briars are like a bunch of little rodent teeth. He says no, it has to do with the topographic profile on a map: it reminded him of—well, of a rat jaw. I think to myself, A lot of things might remind you of a rat jaw. The briar scratches are known as rat bites. Laz once claimed that the briars wouldn’t give you scratches any worse than the ones you’d get from baptizing a cat.

I ask about Meth Lab Hill, wondering what its topographic profile could possibly resemble.

“That’s easy,” he says. “First time we ran it we saw a meth lab.”

“Still operating?”

“Yep,” he laughs. “Those suckers thought they’d never get found. Bet they were thinking, Who the fuck would possibly come over this hill?”

I begin to see why Laz has been so vocal about his new sections: the difficulty of the Bad Thing, the novelty of the prison tunnel. They mark his power over the terrain.

Laz has endured quite a bit of friction with park officials over the years. The race was nearly shut down for good by a man named Jim Fyke, who was upset about erosion and endangered plants. Laz simply rerouted the course around protected areas and called the detour “Fyke’s Folly.”

I can sense Laz’s nostalgia for wilder days—when Frozen Head was still dense with the ghosts of fled felons and outlaws, thick with undiscovered junkies and their squirreled-away cold medicine. Times are different now, tamer. Just last year the rangers cut the briars on Rat Jaw a week before the race. Laz was pissed. This year he made them promise to wait until April.

His greatest desire seems to be to devise an un-runnable race, to sustain the immortal horizon of an unbeatable challenge with contours fresh and unknowable. After the first year, when no one even came close to finishing, Laz wrote an article headlined: THE “TRAIL” WINS THE BARKLEY MARATHONS. It’s not hard to imagine how Laz, reclining on his lawn chair, might look to the course itself as his avatar: his race is a competitor strong enough to triumph, even when he can barely stand.

He used to run this race, in days of better health, but never managed to finish it. Instead, he’s managed to garner respect as a man of principle—a man so committed to the notion of pain that he’s willing to rally men in its pursuit.

VI.

There are only two public trails that intersect the course: Lookout Tower, at the end of South Mac trail, and Chimney Top. Laz generally discourages meeting runners while they’re running. “Even just the sight of other human beings is a kind of aid,” he explains. “We want them to feel the full weight of their aloneness.”

That said, a woman named Cathy recommends Chimney Top for a hike.

“I broke my arm there in January,” she says, “but it’s pretty.”

“Sounds fun,” I say.

“Was it that old log over the stream?” Laz asks wistfully, as if remembering an old friend.

She shakes her head.

He asks, “Was Raw Dog with you when you did it?”

“Yep.”

“Was he laughing?”

A man who appears to be her husband—presumably “Raw Dog”—pipes in: “Her arm was in an S-shape, Laz. I wasn’t laughing.”

Laz considers this for a moment. Then he asks her, “Did it hurt?”

“Think I blocked it out,” she laughs. “But I heard I was cussing the whole way down the mountain.”

I watch Laz shift modes fluidly between calloused maestro and den father. “After nightfall,” he assures Doc Joe, “there will be carnage,” but then he bends down to pet his pirate dog. “You hungry, Little?” he asks. “You might have got a lot of love today, but you still need to eat.” Whenever I see him around camp, he says, “You think Julian is having fun out there?” I finally say, “I fucking hope not!” and he smiles. This girl gets it!

But I can’t help thinking his question dissolves precisely the kind of loneliness he seems so interested in producing, and his runners so interested in courting: the idea that when you are alone out there, someone back at camp is thinking of you alone out there, is, of course, just another kind of connection. Which is part of the point of this, right? That the hardship facilitates a shared solitude, an utter isolation that has been experienced before by others and will be experienced again, that these others are present in spirit even if the wilds have tamed or aged or brutalized or otherwise removed their bodies.

VII.

When Julian comes in from his first loop, it’s almost dark. He’s been out for twelve hours. I feel like I’m sharing this moment of triumph with Laz, in some sense, though I also know he’s promiscuous in this sort of sharing. There’s a place in his heart for everyone who runs his gauntlet, and everyone silly enough to spend days in the woods just to watch someone touch a yellow gate.

Julian is in good spirits. He turns over his pages to be counted. He’s got ten 61s, including one from The Power of Positive Thinking, which came early in the course, and one from an account of teenage alcoholism called The Late Great Me, which came near the end. I notice the duct tape has been ripped from his pants. “You took it off?” I ask.

“Nope,” he says. “Course took it off.”

In camp he eats hummus sandwiches and Girl Scout cookies, barely manages to gulp down a butter pecan Ensure. He is debating another loop. “I’m sure I won’t finish,” he says. “I’ll probably just go out for hours and then drop and have to find my way back in the dark.”

Julian pauses. I take one of his cookies.

He says, “I guess I’ll do it.”

He takes the last cookie before I can grab it. He takes another bib number, for his second round of pages, and Laz and I send him into the woods. His rain jacket glows silver in the darkness: brother robot, off for another spin.

Julian has completed five hundred-mile races so far, as well as countless “short” ones, and I once asked him why he does it. He explained it like this: He wants to achieve a completely insular system of accountability, one that doesn’t depend on external feedback. He wants to run a hundred miles when no one knows he’s running, so that the desire to impress people, or the shame of quitting, won’t constitute his sources of motivation. Perhaps this kind of thinking is what got him his PhD at the age of twenty-five. It’s hard to say. Barkley doesn’t offer a pure form of this isolated drive, but it comes pretty close: when it’s midnight and it’s raining and you’re on the steepest hill you’ve ever climbed and you’re bleeding from briars and you’re alone and you’ve been alone for hours, it’s only you around to witness yourself quit or continue.

VIII.

At four in the morning, the fire is bustling. A few front-runners are incamp preparing to head onto their third loops, gulping coffee or taking fifteen-minute naps in their tents. It’s as if the thought of “the full weight of loneliness” has inspired an urge toward companionship back here, the same way Julian’s hunger—when he stops for aid—makes me feel hungry, though I have done little to earn it. Another person’s pain registers as an experience in the perceiver: empathy as forced symmetry, a bodily echo.

“Just think,” Laz tells me. “Julian’s out there somewhere.”

“Out there” is a phrase that comes up frequently around camp. So frequently, in fact, that one of the regular racers—a wiry old man named “Frozen Ed” Furtaw (like Frozen Head, get it?) who runs in sunset orange camo tights—has self-published a book calledTales from Out There: The Barkley Marathons, The World’s Toughest Trail Race. The book details each year’s comet trail of D.N.F.s and includes an elaborate appendix listing other atrociously difficult trail races and explaining why they’re not as hard.

“I was proud of Julian,” I tell Laz. “It was dark and cold and he could barely swallow his can of Ensure and he just put his head in his hands and said, Here I go.”

Laz laughs. “How do you think he feels about that decision now?”

It starts to rain. I make a nest in the back of my car. I type notes for this essay. I watch an episode of The Real World: Las Vegasand then turn it off, just as Steven and Trishelle are about to maybe hook up, to conserve power for the next day and also because I don’t want to watch Steven and Trishelle hook up; I wanted her to hook up with Frank. I try to sleep. I dream about the prison tunnel: it’s flooding, and I’ve just gotten a speeding ticket, and these two things are related in an important way I can’t yet fathom. I’m awoken every once in a while by the mournful call of taps, like the noises of a wild animal echoing through the night.

Julian arrives back in camp around eight in the morning. He was out for another twelve hours, but he managed to reach only two books. There were a couple hours lost, another couple spent lying down, in the rain, waiting for first light. He is proud of himself for going out, even though he didn’t think he’d get far, and I am proud of him, too.

We join the others under the rain tent. Charlie Engle describes what forced him back during his third loop. “Fell flat on my ass going down Rat Jaw,” he said. “Then I got up and fell again, got up and fell again. That was pretty much it.”

There’s a nicely biblical logic to this story: it’s the third time that really does the trick, seals the deal, breaks the back, what have you.

Laz asks whether Charlie enjoyed the prison section. Laz asks everyone about the prison section, the way you’d ask about your kid’s poem: Did you like it?

Charlie says he did like it, very much. He says the guards were friendly enough to give him directions. “They were good ol’ Southern boys, those guys,” and I can tell from the way he says it that Charlie considers himself a good ol’ Southern boy as well. “They told us, ‘Just make yer way up that there holler…’ and then those California boys with me, they turn and say, ‘What the fuck is a holler?’”

“You should have told them,” says Laz, “that in Tennessee a holler is when you want to get out but you can’t.”

“That’s exactly what I said!” Charlie tells us. “I said: when you’re standing barefoot on a red ant hill—that’s a holler. The hill we’re about to climb—that’s a holler.”

The rain is unrelenting. Laz doesn’t think anyone will get the full hundred this year. There were some stellar first laps, but no one seems strong enough now. People are speculating about whether anyone will even finish the Fun Run. There are only six runners left with a shot. If anyone can finish, everyone agrees, it will be Blake. Laz has never seen him quit.

Julian and I share a leg of chicken slathered in BBQ sauce. There are only two left on the grill. It’s a miracle the fire hasn’t gone out. The chicken’s good, and cooked as promised, steaming in our mouths against the chilly air.

A guy named Zane, with whom Julian ran much of his first loop, tells us he saw several wild boars on the trails at night. Was he scared? He was. One got close enough to send him scurrying off the edge of a switchback, fighting stick in hand. Would a stick have helped? We all agree, probably not.

A woman clad in what looks like an all-body windbreaker has packed a plastic bag of clothes. Laz explains that her husband is one of the six runners left. She’s planning to meet him at Lookout Tower. If he decides to drop, she’ll hand him his dry clothes and escort him down the easy three-mile trail back into camp. If he decides to continue, she’ll wish him luck as he prepares for another uphill climb—soaked in rainwater and pride, unable to take the dry clothes because accepting aid would get him disqualified.

“I hope she shows him the dry clothes before he makes up his mind,” says Laz. “The choice is better that way.”

The crowd stirs. There’s a runner coming up the paved hill. Coming from this direction is a bad sign for someone on his third loop—it means he’s dropping rather than finishing. People guess it’s J.B. or Carl—must be J.B. or Carl, there aren’t many guys still out—but after a moment Laz gasps.

“It’s Blake,” he says. “I recognize his walking poles.”

Blake is soaked and shivering. “I’m close to hypothermia,” he said. “I couldn’t do it.” He says that climbing Rat Jaw was like scrambling up a playground slide in roller skates, but otherwise he doesn’t seem inclined to offer excuses. He says he was running with J.B. for a while but left him on Rat Jaw. “That’s bad news for J.B.,” says Laz, shaking his head. “He’ll probably be back here soon.”

Laz hands the bugle over. It’s as if he can’t bear to play taps for Blake himself. He’s clearly disappointed that Blake is out, but there’s also a note of glee in his voice when he says: “You never know what’ll happen around here.” There’s a thrill in the tension between controlling the race and recognizing it as something that will always disobey him. It approximates the pleasure—pleasure?—of ultra-running itself: the simultaneous exertion and ceding of power, controlling the body enough to make it run this thing but ultimately offering it to the uncontrollable vagaries of luck and endurance and conditions, delivering oneself into the frisson of this overpowering.

Doc Joe motions me over to the fire pit. “Hold this,” he says, and shoves a large rectangle of aluminum siding in my direction. He balances a fallen tree branch against its edge to make a rain roof over the fire, where the single remaining breast of chicken is crisping to a beautiful charred brown. “Blake’s chicken,” he explains. “I’ll cover it with my body if I have to.”

IX.

Why this sense of stakes and heroism? Of course, I have been wondering the whole time: why do people do this, anyway? Whenever I pose the question directly, runners reply ironically: I’m a masochist; I need somewhere to put my craziness; type A from birth; etc. I begin to understand that joking about this question is not an evasion but rather an intrinsic part of answering it. Nobody has to answer this question seriously, because they are already answering it seriously—with their bodies and their willpower and their pain. The body submits itself in utter earnest, in degradation and commitment, to what words can speak of only lightly. Maybe this is why so many ultra-runners are former addicts: they want to redeem the bodies they once punished, master the physical selves whose cravings they once served.

There is a gracefully frustrating tautology to this embodied testimony: Why do I do it? I do it because it hurts so much and I’m still willing to do it. The sheer ferocity of the effort implies that the effort is somehow worth it. This is purpose by implication rather than direct articulation. Laz says, “No one has to ask them why they’re out here; they all know.”

It would be easy to fix upon any number of possible purposes—conquering the body, fellowship in pain—but it feels more like significance dwells in concentric circles of labor around an empty center: commitment to an impetus that resists fixity or labels. The persistence of “why” is the point: the elusive horizon of an unanswerable question, the conceptual equivalent of an un-runnable race.

X.

But: how does the race turn out?

Turns out J.B. manages to pull off a surprising victory. Which makes the fifth paragraph of this essay a lie: the race has nine finishers now. I get this news as a text message from Julian, who found out from Twitter. We’re both driving home on separate highways. My immediate thought is, Shit. I wasn’t planning to focus on J.B. as a central character in my essay—he hadn’t seemed like one of the strongest personalities or contenders at camp—but now I know I’ll have to turn him into a story, too.

This is what Barkley specializes in, right? It swallows the story you imagined and hands you another one. Blake and Carl—both strong after their second loops, two of my chosen figures of interest—didn’t even finish the Fun Run.

Now everyone goes home. Carl will go back to his machine shop in Atlanta. Blake will help his daughter train for the trials. John Price will return to his retirement and his man-wagon. Laz, I discover, will return to his position as assistant coach for the boy’s basketball team at Cascade High School, down the highway in Wartrace.

XI.

One of the most compelling inquiries into the question of why—to my mind, at least—is really an inquiry around the question, and it lies in a tale of temporary madness: A.T.’s frightening account of his fifth-loop “crisis of purpose” back in 2004.

By “crisis of purpose,” he means “losing my mind in the full definition of the phrase,” a relatively unsurprising condition, given the circumstances. He’s not alone in this experience. Another ultra-runner named Brett Maune describes hallucinating a band of helpful Indians at the end of his three-day run of the John Muir trail:

They watched over me while I slept and I would chat with them briefly every time I awoke. They were very considerate and even helped me pack everything when I was ready to resume hiking. I hope this does not count as aid!

A.T. describes wandering without any clear sense of how he’d gotten to the trail or what he was meant to be doing there: “The Barkley would be forgotten for minutes on end although the premise lingered. I had to get to the Garden Spot, for… why? Was there someone there?” His amnesia captures the endeavor in its starkest terms: premise without motivation, hardship without context. But his account offers flashes of wonder:

I stood in a shin-deep puddle for about an hour—squishing the mud in and out of my shoes…. I walked down to Coffin Springs (the first water drop). I sat and poured gallon after gallon of fresh water into my shoes…. I inspected the painted trees, marking the park boundary; sometimes walking well into the woods just to look at some paint on a tree.

In a sense, Barkley does precisely this: forces its runners into an appreciation of what they might not otherwise have known or noticed—the ache in their quads when they have been punished beyond all reasonable measure, fatigue pulling the body’s puppet strings inexorably downward, the mind gone numb and glassy from pain.

By the end of A.T.’s account, the facet of Barkley deemed most brutally taxing, that sinister and sacred “self-sufficiency,” has become an inexplicable miracle: “When it cooled off, I had a long-sleeve shirt. When I got hungry, I had food. When it got dark, I had a light. I thought: Wow, isn’t it strange that I have all this perfect stuff, just when I need it?”

This is benevolence as surprise, evidence of a grace beyond the self that has, of course, come from the self—the same self that loaded the fanny pack hours before, whose role has been obscured by bone-weary delusion, turned other by the sheer fact of the body losing its own mind. So it goes. One morning a man blows a conch shell, and two days later—still answering the call of that conch—another man finds all he needs strapped to his own body, where he can neither expect nor explain it.

Leslie Jamison’s most recent book is The Empathy Exams.