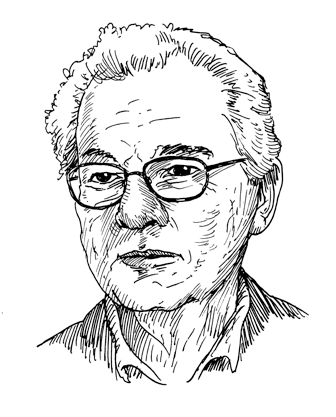

The following is an excerpt of Chris McCoy’s interview with legendary cinematographer Gordon Willis. The full interview is in the Believer’s March-April film issue. Willis died on Sunday, May 18.

Last week my friend Gordon Willis died. Gordon moved into my parents’ neighborhood about the same time I got out of film school, when I had to move back home because I had no money and no connections and no idea what to do next. I got to know him that summer by walking across the street whenever he was down in the dirt working on his garden, which was a lovely garden. We talked about his time in the sixties/seventies film industry, we talked about Woody Allen and Francis Ford Coppola, I pretty much just asked him whatever questions I could come up with as a dumb twenty-two-year-old who, aside from a couple of internships, had no experience in the film industry. He was patient with me and he loved talking about movies, though he admitted he couldn’t see them as well as he once did because his eyesight was deteriorating, which I used to tell him was like Beethoven losing his hearing. He agreed, which I always thought was funny. The man knew his shit.

After I moved to Los Angeles I would come home a couple of times a year—for some portion of the summer, and then over Christmas break, which was my favorite time because it meant I got to stop by Gordon’s house and ask him about the movies that had been nominated for Oscars that year. He always saw everything, had opinions on everything. He hated Los Angeles, but he liked hearing about my work. When I told him I was having a hard time finding a copy of Hal Ashby’s first movie The Landlord on DVD—a film he shot—he sent me his personal MGM Limited Edition Collection copy with a note saying he was pleased with the transfer and it was very close to the original.

Recently the Believer asked me to interview him, and I got the chance to sit down with him alone for two hours with a microphone. He had an extraordinary life, and I tried my best to get as many of his experiences into the piece as I could, though I’m sure I failed. His life was too rich for a few pages.

Looking back, the best piece of advice he ever gave me was something that didn’t go into the piece, which he told me years ago when I was starting out: “Just hang around.” I took this to mean hang around people you thought were talented, hang around people whose work you liked, and be the kind of person other people want to hang out with. The amount of knowledge that Gordon took with him when he passed is incalculable—simply put, without this man, movies don’t look like they do today. I’ll miss him terribly, but it’s nice to know his work is going to be watched forever, and I’m glad I get to visit him again every time I watch Annie Hall or the Godfather or that copy of The Landlord he sent me in the mail.

—Chris McCoy

THE BELIEVER: Do you miss New York?

GORDON WILLIS: I miss it. But I don’t think I could deal with it anymore, is the truth of the matter.

BLVR: Your movies captured a version of New York that doesn’t exist anymore. They’re like historical documents of what these areas once looked like.

GW: It’s kind of interesting. My daughter said, “You shoot romantic reality,” and I said, “That’s probably true.”

BLVR: I love that, “romantic reality.”

GW: She’s very perceptive. That’s what it is, romantic reality.

BLVR: It’s interesting because between Woody and Coppola and Pakula, you’ve dealt with a range of different personality types. What has allowed you to be able to communicate with such a wide range of very different directors?

GW: I don’t know. In my particular case, with Woody, it was a very good association. It was probably my favorite. I’m very quick to tell somebody how they should do it—from a blocking-photographing point of view. I offer a lot. Woody liked most of it and that he didn’t have to deal with it. He said once, “We both hate the same things.” Which is true. I think he really got worried, by the time we finished shooting, that I was doing a lot, and I think he probably said, “Well, I better step out of here.” But we still remain friends.

BLVR: How was it different with Coppola?

GW: Woody and I never sat down and went through the script page by page. What we did was go over the material as it was scheduled. We would look at the locations. Most of the blocking and how-to were done on the day. We’d get to the studio or location, he’d run the scene, I’d make suggestions, and when he was comfortable, we’d block, light, and shoot. This happened with the least amount of fanfare. It was pleasant. It was like working with your hands in your pockets.

I would say that with Francis, there was a certain amount of chaos. On Godfather I, it was completely understandable. Paramount was treating him badly, and he was under a lot of pressure. I wasn’t too pleasant at times, and sometimes there were arguments about shot structure, what to shoot, when to shoot. The first movie was done like you were trying to blow up an ammo dump: lots of covert thinking, bad communication.

A quick story about Godfather I that still makes me laugh: in the wedding when Al Pacino comes out of the church with Apollonia and starts walking down the hill toward town, Francis decided to have these little firecrackers along a stone wall by the road. I looked at them and turned to Francis: “Don’t you think we should try these out first? They’re the size of my little finger—big, don’t you think?” Francis says, “No, no, they use them all the time.” I asked the prop man to light a small string of them just to see. He put some on the wall and held out his cigarette. They went off. The prop man fell down, pieces of stone went everywhere, everybody hit the ground. “It must be a hit!” We did not use the firecrackers. There was never a dull moment with Francis. They also used too much dynamite in the car when we blew up Apollonia. It put a crack down the side of the villa. It was never a good idea to turn your back and miss what was being said. Francis tended to make a different movie with whoever he was talking to.

BLVR: Given the look of The Godfather, its darkness, how did you not cause the studio to have an aneurysm?

GW: That almost happened. I thought, I don’t know, I just think this dirty, brassy look seems to be right for the movie, it just seems right to me. I think Francis, bless him, took most of the beating for it from the studio, as opposed to me, because they were beating him up a lot. They wanted to fire him and they wanted to fire others, so they thought, Jesus, let’s not fire Gordon. I give Francis credit for the fact that they didn’t. He knew I was doing the right thing, even though we were going head-to-head at times.

BLVR: Did you have to front-load the film with really good shots to convince them it would look OK?

GW: The very opening of the movie, we start on the black face pleading for his daughter, and then we’re slowly pulling back and revealing what was going on. That caused quite a problem because after we watched that at the Gulf and Western Building—which was Paramount at that point—Al Ruddy, who was the producer, came over and said, “It’s really dark.” I said, “Nah, it’s dark now, but wait, it’ll be surrounded with visual support, you’ll see.” I already had the concept of this bright Italian wedding going on outside all these bottom-feeders in this room.

BLVR: In Godfather II and Zelig, you came up with this palette that is now what the world thinks of as “nostalgia.” If you’re looking at Godfather II, those warm yellows and oranges—you created that.

GW: Right.

BLVR: Could you talk about how you came up with that? They have a memory element to them.

GW: I had a discussion with Francis one day. He said, “How are we going to know where we are in this story?” I said, “There’s a simple way of showing it. When you cut to New York, you say ‘New York’ right at the bottom.” It always works and it’s very acceptable. Then nobody’s asking, “Where are we?” “Visually,” I said, “I’m not going to change the color of anything, but I’m going to change the quality of the photography, so that when you go from 1958 in Tahoe, and then we cut back to De Niro on the streets of New York at the turn of the century, you’re going to know that you’ve made a turn.” It would be a mistake to do something stupid like: here we are in 1958, and now here we are at the turn of the century, so the turn of the century is going to be in black and white. That becomes invasive for an audience. They get confused, and it’s pretentious and it’s dumb. Instead, it’ll all be the same color, but the quality of the visuals will change in the period work. We’ll take the film and push it back a bit further, so it doesn’t look the same but it doesn’t get in the way.

BLVR: Was there something inside you that said: Our memories fade as we get older, and this is going to be reflected on the film? Because it sounds like that’s what you’re talking about.

GW: Right, you just turn it. I’ve always hated the fact that somebody shoots a movie that takes place in 1872 or whatever, and they put everybody on their horses and dress them up in what they’re supposed to be wearing, then it looks like they shot it yesterday. I hate that.

BLVR: You got back together with Coppola to shoot Godfather III. What was your dynamic like after sixteen years had gone by?

GW: It was fine. We were friendlier on Godfather II, actually. Godfather I was pretty bad. It was really a shit bath for everybody, but I give Francis enormous credit for coming back the second time. I’m glad he did.

BLVR: Greatest sequel of all time.

GW: Yes, I think it’s a better movie. But Godfather III, I don’t know. Not everyone has an opportunity to get together years later and work with all the same people. I thought, from that standpoint, it was worth it. The movie’s not as good, and I think he sort of got lost about writing it, but generally speaking, it was a good dynamic.

BLVR: Since you guys had a good collaboration on Godfather II, did he try to bring you into Apocalypse Now?

GW: [Laughs] I’m so grateful I didn’t get involved with that. No, he never asked me, because he was sort of having a love affair with Vittorio [Storaro] at that point, and I think Vittorio, as a person, is actually the only one who can put up with that in the middle of nowhere.

I’m a great believer in relativity when making movies—relativity, in my mind, meaning “Light to dark, big to small, good to bad.” You visually embrace these things to enhance transitions and instantly paint environments and moods. I would discuss this with Francis from time to time while shooting the Godfather movies—using sizes and distance in the cuts, or dark spaces to light spaces to help tell the story.

When all that was over, he went on to Apocalypse Now. I was happy I had nothing to do with that. I hate the jungle. Anyway, I was working on some other movie and I got a message from Francis: “I finally understand relativity. I’d like you to shoot all the rest of my movies.” I never heard from him again until Godfather III.

BLVR: That seems like a very funny thing—to randomly get a telegram from Coppola in the middle of Apocalypse Now.

GW: Well, Francis discovered a lot of mind-altering alternatives to life while he was in the jungle.

BLVR: The filmic language you’ve created is unbelievable.

GW: I’m glad. One of the things I wish would be happening now, which doesn’t seem to be happening much—maybe I’m missing it—but I’m so thirsty for narrative in the movies. Just decent narrative. Narrative filmmaking is right on the edge of not existing anymore.

BLVR: What is narrative filmmaking to you?

GW: Good storytelling. I always said that you could photograph a good story badly and it wouldn’t matter, but you can shoot a bad story well and it’s not going to help the story at all. It’s not. But you get the two together, and it’s great.

BLVR: We’ve had discussions in the past about Hal Ashby’s debut, The Landlord, which you shot.

GW: He and I got along very well. Hal was a devoted drug user. But he was a very fine editor, and he knew film.

BLVR: Did he ask you to do Harold and Maude?

GW: He wanted me to, but I lived on the East Coast and I had not made the transition into the LA union at that point.

BLVR: Was the West Coast guild trying to keep the East Coasters out of it?

GW: Yes. It was a very kind of formidable group they were running.

BLVR: Did you feel like the New York cinematographers were the outsiders?

GW: They were for a long time. But people who grew up shooting on the streets of New York, you learned how to shoot in a different way. At least I did. I didn’t fool around. I look at the quickest way to get something done and make it meet the mark. I’m shooting it because it’s the most effective way of doing it.

BLVR: The Landlord shows a very gritty New York, using very realistic lighting. How did you decide to use that kind of lighting?

GW: The thing about film is that your eye is selective. Film isn’t. You have to make film do what you want. Simply photographing something doesn’t do it. You have to know how to apply light and know what it does on film. A huge problem in movies—or with people who work on movies—is that two people can look at the same thing but they don’t necessarily see the same thing. It’s not going to look like what you’re looking at. When I step into a room or step on a set, I instantly transpose what it’s going to look like in the camera onto the screen. I’ll just look at something, anything—you sitting on the couch—and [makes a click sound] it’s immediately framed up. That’s why it was really easy for me to block movies. I’d have people there standing in the middle of a room, bewildered, not knowing what the hell to do.

People don’t see what they’re looking at. They’ll find a location, or a room, or even a person, and they don’t see it. They’ll look at it, but they’ll immediately want to move it or change it to something they’re more comfortable with. I’d say, “Then why are we here? What are we doing here if you want to do all of that? It looks great now, don’t fix it.” A lot of people think, Well, I’m being paid all this money, I have to do something. But the person who’s really worth a lot of money is the one who looks at something and knows what not to do—don’t do that, don’t do this, leave this here. I always found that a more important decision—what you don’t do.

Then, if you do do something, make it definitive. Well, what if this doesn’t work? I hate when somebody says, “This may not work.” You’ll never get anywhere with that. I’ve pushed a lot of people out of my way—I don’t mean physically—over them being afraid something isn’t going to work. They say, “What are my options?” Well, you have no options. You’ve got to process this idea and follow it through. If it fails, then it’s over. You failed it—next time, do something else. But don’t say, “What are my options?” Because what you’re saying is “What if this doesn’t work?” Well, it’s not going to work, because in the back of your mind you’ve already got that in your head.

BLVR: It’s been fifteen years since you shot a movie. Have you been tempted since to return to film?

GW: Woody actually contacted me a few years ago. He wanted to do something in New York. I said, “I’m sorry, my eyesight is now at a point where I can’t do it for you.” I said, “All women look beautiful to me now.”

Illustration by Tony Millionare