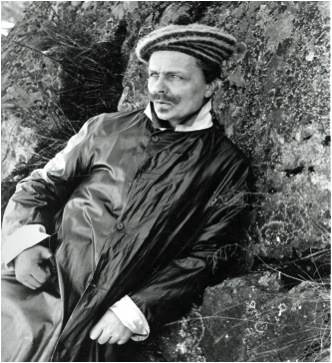

In 1906 the playwright August Strindberg invited a friend to tea in his Stockholm apartment. When the friend walked into the living room, he found that all the chairs and sofas weren’t occupied by other guests but by photographs depicting Strindberg himself. When the friend asked why he had taken so many photos of himself, Strindberg explained that the photos other people took of him were always inadequate. “I don’t care a thing for my appearance,” he said, “but I want people to be able to see my soul, and that comes out better in my photographs than in others.”

Strindberg, in the ardent and unhinged way he announced a lot of things, once announced that the stars in the sky were peepholes in a wall. He believed it was possible to take a photograph of himself and capture something essential: his soul. And he believed it was possible because he was the one who could control the image. That element of control in self-photography is important, and it’s possible that to take a picture of yourself may seem to reveal something, while in reality it discloses nothing.

We’re accustomed to accepting that a photograph can lie—Photoshop can slim waists, tighten jaw lines, and give somebody a glass of juice to hold—but those aren’t the things that make a photograph artful or even poignant. We continue to believe a picture speaks a thousand words.

And we’re especially liable to believe the thousand words we perceive in a picture if it’s a picture of a woman. Women more than men have spent most of history being seen and not heard. We’ve spent five hundred years trying to find the source of the Mona Lisa’s smile. We look for the anguish in the faded picture of Virginia Woolf, we sense the trembling behind the stretched smile of Lindsay Lohan emerging from a doorway into a neon-lit street at 3am, the compromised grace of an anonymous teenage girl lit up by the flash of the smart phone she holds in her hand. We’re used to anatomising the essence of a woman in the images that have been taken of her.

If a woman took tens of thousands of photographs, many of them pictures of herself, and then never showed them to a soul, never meant for anybody to see them at all, what could you know about that person from her photographs?

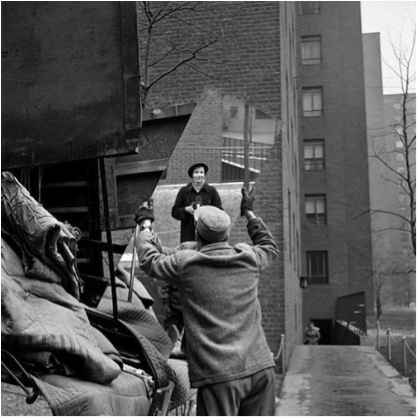

That’s the question implicitly asked about Vivian Maier, the subject of a recently released documentary. Finding Vivian Maier tells the story of a mid-twentieth century street photographer who has been plucked from obscurity in the last five years to wide critical acclaim. The documentary is the work of John Maloof, the man who stumbled upon her photographs in 2007 when he bought a box of undeveloped negatives at an estate auction. He didn’t investigate the contents of the boxes or the name attached to them until 2009, when he performed a casual Google search and learned that the woman had died, old, alone and destitute, several days earlier. Upon developing some of the negatives Maloof unearthed some astonishingly good photographs. More investigation found that over the course of her life Maier had accumulated over 150,000 rolls of unprinted film which she had stored, but in most cases never made an effort to print.

The photographs, which have now been exhibited around the world, demonstrate that Maier was a woman with an impressive creative vision whose work stands among the best American photography of the twentieth century. But during her life she worked as a nanny, taking care of other people’s children in the moneyed households of suburban Chicago. She spent her days stalking the streets with her charges in tow, a Rolleiflex camera slung almost permanently around her neck.

The documentary attempts to get some sense of Maier from the employers and children she worked with. But it’s clear that there’s little insight to be gained from the people who knew her. Certainly Maier appears both eccentric and prickly. We know she was militant about her privacy, that she insisted her employers allow her separate locks on her bedrooms door, and that she refused to give her name or phone number to business people and casual acquaintances. She was often cruel and frightened the children who were in her care.

The film struggles to integrate Maier’s artistic talent with her abrasive character, attempting to paint her as sympathetic in the same way that others have attempted to make difficult women like Amy Winehouse seem more likable after their deaths, rhapsodizing about her beauty and talent and the tragedy of her loss while avoiding discussing any of the caustic elements of her character. The filmmakers hint that her fascination with “the bizarreness of life, the unappealingness of human beings” must be symptomatic of a troubled psychology. There are some unfounded suggestions that she could have been molested. The film flashes through her photographs all the while, as though they might help give weight to the speculation.

But what’s clear is that Maier surrounded herself in contradiction. She always posed people for her photographs, says one of the children she looked after. Or, says another, she never posed anyone. She asked one employer to call her Miss Maier, but never Vivian. Except for those who did call her Vivian, but never Viv. Then again, another family wouldn’t dream of calling her anything other than Viv. She spoke with a European accent, but she was born in New York. A linguist swears her accent was fake, but another acquaintance explains that it was the accent of somebody who’d worked hard at polishing her English.

There is never any consensus. The film juxtaposes all the scraps of information together, as though in the wacky mystery of the thing we might be able to find some little essential truth about the woman. But Maier remains a cipher, and so the film looks for answers in her photography, particularly the pictures she took of herself.

While Maier did photograph others, her body of work comprises many self-portraits. She photographed her expression in mirrors, panes of glass, shop windows, curves of aluminium, and her shadow creeping across pavement and lawns. The film lingers on these images, as though the careful study of the photographs Maier took of herself will allow us to perceive whatever was essential about her. Her “soul”, if you want to use Strindberg’s word.

The film’s premise is that the examination of Maier’s photographs will facilitate the process of discovering who she really was, but to do so assumes that Vivian Maier needs both finding and discovering. The film is convinced that Maier, despite a lifetime of carefully guarded privacy, would have wanted to be found. And an attempt to “find Vivian Maier” in her in her pictures is seductively easy: the photographs she took of herself have an inscrutable unnerving quality that invites biographical speculation. The effect of that speculation, and the insistence on needing to find the woman in the photograph, places more importance on Maier’s character and than the art itself.

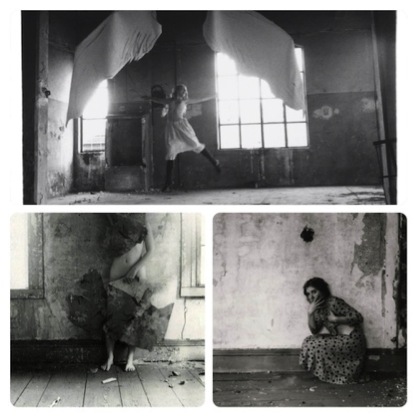

The biographical speculation prompted by a woman turning a camera lens on herself is not unique to the discussion of Vivian Maier, in fact it bears resemblance to the reception of another troubling female photographer only appreciated after her death, Francesca Woodman.

The story of Francesca Woodman has become a kind of archetypal fairytale of the 1970s New York art world. She was raised in a family of artists (the subject of the documentary The Woodmans) and began taking photographs when she was thirteen. She was preternaturally gifted. She attended the Rhode Island School of Design, and then moved to New York after graduation. She struggled to have her work taken seriously, and combined with a series of personal crises, she became increasingly unhappy. In January 1981, when she was twenty-two years old, she jumped from a loft window and died. Her work has since been widely praised, despite, and sometimes because of, the allure of art coupled with tragedy and the early death of a young woman. The public image of her is not far removed from an image of Ophelia floating forlorn and beautiful in the still water, strewn with flowers.

Francesca Woodman’s most frequent subject was herself, often naked, in black and white, either in nature or ramshackle rooms with peeling wallpaper and the light streaming through high, uncovered windows. Like Maier, her self-portraits often included mirrors, glass or reflective metal, often deliberately blurring her figure so that she resembled a ghost only briefly inhabiting the room. She was frequently told her work came across as personal, self-involved, and people had a hard time disentangling her physical presence from her work even before personal tragedy infected the ambience. In a letter to Suzanne Santoro on June 18, 1980, six months before her death, Woodman wrote “This fall 3 seperate (sic) art dealers insinuated in various ways that to understand my work they would have to sleep with me and the idea that my pieces seems to evoke that kind of response revolts me is diametrically opposed to what I was trying to express.”

Walter Benjamin famously accused photography of helping to contribute to the decline of what he called the “aura” in traditional artwork—after photography, art was no longer special or singular anymore because it could always be reproduced. Instead, Benjamin complicated things by associating portrait photography, in particular a portrait of Kafka as a child, with a kind of post-auratic aura, which transcends historical or technological categories through an imaginary encounter in which Benjamin projects himself into the photograph and mixes up memories of Kafka’s childhood with his own. Benjamin could have made up something about Kafka’s childhood, but his natural instinct was to insert himself instead, as if he were taking the portrait of himself.

Part of the problem surrounding Francesca Woodman’s legacy is that it’s all too easy to identify with the real and documented aspects of her anguish, and that identification can bleed into the way her photographs are perceived. We imagine that in photographs where she covers her face in strips of wallpaper, or leaps ghostly across a ruined room, that she is communicating in a kind of code, that we understand something that isn’t being said, something beyond words, because we see it right there in the pictures she took of herself.

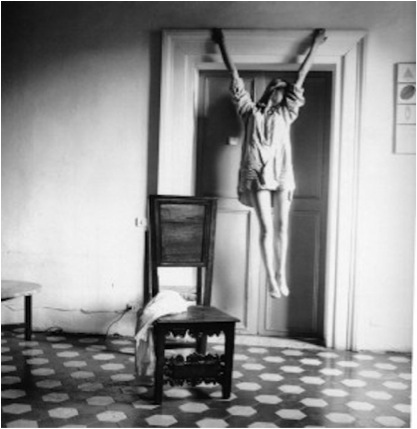

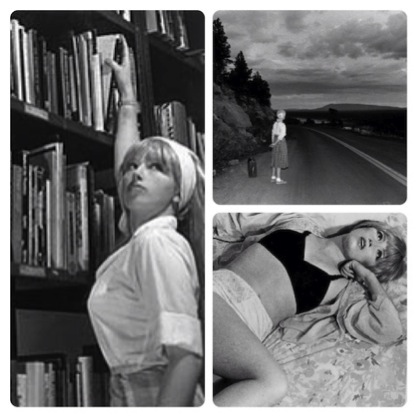

Another photographer working at the same time as Woodman who also made herself the subject of her work is Cindy Sherman. She is arguably best known for the Untitled Film Stills series, which are technically self-portraits, although she is nearly indistinguishable from one image to the next. While Sherman took photographs of herself, fewer people attempt to transcribe something essential from Sherman’s photographs in the way people attempt to find and discover Woodman and Maier in theirs. That’s largely because Sherman’s entire project in the Untitled Film Stills is to thwart attempts at discovery. But they still try. In a 2011 interview with The Guardian, Simon Hattenstone asks Sherman about her early relationship to make up. “I was really ambivalent about it because I still liked it,” she says, “but you did not wear make-up, you did not dye your hair, you didn’t wear a bra—we were all natural. Don’t shave or anything. In some of the really early work, you can see my hairy legs.” From her answer Hattenstone still attempts to extrapolate a personal angle, writing, “So even though it’s not autobiographical, the work is about her sense of self.”

In the series, Sherman plays a host of different roles that perform variations of female identity, and succeeds in being both all and none of those representations. The more the pictures of herself multiply—draped across unmade beds, reaching for books on high shelves, waiting alone by a highway with a suitcase by her side—the more the idea of Sherman recedes like a mirage, in inverse proportion to the multiplication of her image. Sherman has stated that her photographs are not self-portraits, even though, technically, they are. Her photographs point to the tricky issue of the ‘self’ in self-portraiture, because, the thing is, a self-portrait is not necessarily a portrait of the self.

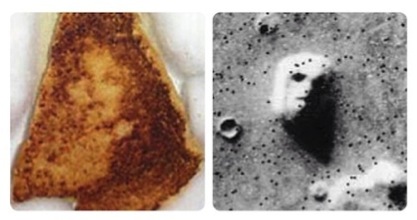

Our urge to try and excavate the souls of women from the photographs they’ve taken of themselves strikes me as a kind of pareidolia, the psychological phenomenon in which our minds latch on to pieces of vague and random stimuli, and imbue them with significance. It’s what makes us see candy canes in cloud formations, faces on the surface of Mars, visions of the Virgin Mary in grilled cheese sandwiches. When we look at a picture of a person they’ve taken of themselves, particularly when it’s a picture of a woman, we become hungry for some kind of disclosure. We want to understand her from her image, and in doing so we lose the ability to see clearly. Our minds imbue the images with significance on the scantest of stimuli.

The problem is that what seems like disclosure in Vivian Maier and Francesca Woodman’s photography is vague and impossible to explain. No matter how much the images reveal they keep the better part of the mystery to themselves. The self-photographed figures of Woodman and Maier inhabit their images as both embrace and warning. Their images are affirmations that affirm nothing.

Taking pictures of yourself implicitly acknowledges that there is a division and a difference between the ways you perceive yourself, and an external self that’s perceived by others. Roland Barthes in Camera Lucida, his long meditation on photography, described the phenomenon this way: “the Photograph is the advent of myself as other: a cunning dissociation of consciousness from identity”. The difference is that when Barthes was writing in 1980 that dissociation happened less frequently than it does today, now that photography no longer has the same function it used to. Photography is so ubiquitous now, so utterly pervasive, that a photograph has less to do with content and much more to do with the way we use it to communicate. As a means of expression. For most of us photography has become a visual conversation more linguistic than formally artistic.

When you turn the camera or the smartphone screen on yourself, you force into the foreground the consciousness of yourself as other. When you take a photograph of yourself you look at yourself in the first person, but it’s always with a different perspective. You look in the second person, or even the third. You’re communicating, not documenting.

The ability to look in first, second, and third person at the same time is imperative: it gives you control over your image.

Women have been the subjects, muses, and symbolic vehicles of imagery for most of Western civilization. And for most of that history, men have determined the meaning of those images. It’s helped to facilitate a state of things in which we feel ready to discover inherent meaning about a woman, her soul and her psychology when we look at an image of her, whether painted, drawn, etched, photographed, filmed or videotaped.

It was historically much harder for women to be the subject or muse of her own image, an image that she controlled, without special training, expensive equipment, and an abundance of free time. Then in 2004, we were suddenly able to photograph all the time. We had cameras in our phones. Our phones were always in our pockets. We could photograph everything, all the time. It was also then that we began to exist online, and when we began to learn how to package and present ourselves as product. This dovetailed with the proliferation of the “selfie”.

The cultural phenomenon of the selfie tends to be discussed most often when it comes to young women, although, to be clear, I’m not suggesting that a snapshot somebody took on their phone is equivalent to the artistic practices of Vivian Maier or Francesca Woodman. But the urge to find and discover the truth about a woman in the photograph she has taken of herself is a cultural phenomenon that doesn’t make distinctions between photography-as-art and photography-as-communication.

There’s a cultural narrative that’s been told about what it means when young women photograph themselves, and it tends to go heavy on the use of the words sexualization and narcissism. The narrative explains that the culture, such as it is, has produced both sexualized and self-involved young women, and that the photographs they incessantly take of themselves is proof. A woman who engages in either of these things is at risk of being thought of as sexualized, narcissistic, or both, and therefore deviant, but passively so. What she has to say for herself is deemed inauthentic because the culture that has produced her inhibits free choice and critical thought. Regardless of the woman or the photograph, the narrative implies that you can tell exactly who the young woman is from the photograph she’s taken of herself. And it’s never good.

That narrative relies on an idea of the purpose and use of photography which has its roots in the past.

After 2004 and the advent of camera phones, young women, always the muse and subject of images, found it was much easier for her to be a muse for herself and other women. Photography wasn’t so serious anymore, and you didn’t have to be defined by your image because the limits of photography were infinite. There were so many images you could take that just one didn’t define you. You could play around with your image until it fit, and you could control the camera. This was facilitated by the growth of social media, blogs and forums, in particular the visual pockets of the web dedicated to fashion and hair and tattooing and nail art. But it also corresponded with the rising popularity of a particular kind of street photography, the over-saturated Instagram filter kind that’s permeated the aesthetics of contemporary advertising. The popularity of those images announced to young women that it was permissible to be silly and reckless and stupid and play around with your image in front of a camera and that was OK.

A photograph you take of yourself sits at the nexus of control and self-exposure. It blurs the line between reality and the performance of a fantasy self. Diane Arbus once said that, “A photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you the less you know.” We may think we perceive some essential truth about somebody’s character or soul when we look at a photograph they’ve taken of themselves, but it’s nearly always runaway guesswork. The woman in the photograph who controls her own image is, like Maier and Woodman, an affirmation that affirms nothing.

There is a reciprocal relationship in-between seeing and being seen, and rarely is it simple to define. The way a woman might aspire to look, or the person she might aspire to be, might be refracted through cultural ideals, but it is never those things alone. How you imagine yourself looking, how you want to look, and who you imagine yourself to be and who you want to be at this very moment, can change and transmute in the frame of the photograph. Taking a picture of yourself is always dependent on context, on the story you’re telling in the first person as well as the second and the third. Most photographs young women take of themselves disclose much less than the narrative tends to imply. You can’t tell exactly who she is from the photograph. To quote John Ashberry the image “protect(s) what it advertises.”

The derision of the photographs young women take of themselves—as vain and banal—is a generalization not far off from the standard read on Maier and Woodman.

To insist on finding the woman in the photograph only obscures what photography can do, and the infinite things a woman might be doing when she turns a camera on herself, which have nothing to do with revealing her soul. A photograph, like Strindberg’s stars, is a peephole in a wall. It shows us something, but there’s an awful lot that it doesn’t reveal.