In this series Colin Winnette asks writers he admires to recommend a book. He reads it. Then they talk about it.

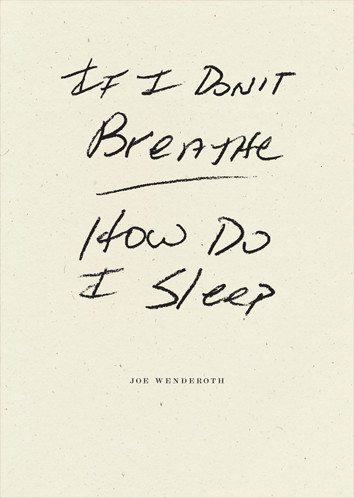

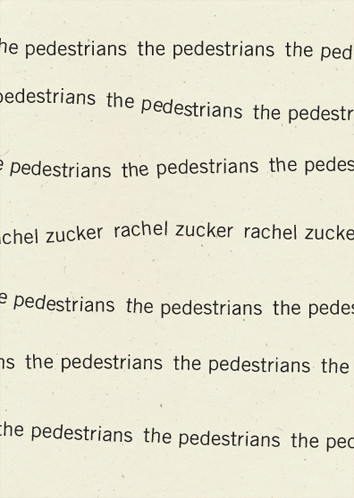

For this installment, Victoria Chang recommended Joe Wenderoth’s If I Don’t Breathe, How Do I Sleep and Rachel Zucker’s The Pedestrians.

Victoria Chang’s third book of poems, The Boss, was published by McSweeney’s in 2013 as part of the McSweeney’s Poetry Series. Her second book, Salvinia Molesta, was published by the University of Georgia Press as part of the VQR Poetry Series in 2008. Her first book, Circle, won the Crab Orchard Review Open Competition Award and was published by Southern Illinois University Press in 2005. She also edited an anthology, Asian American Poetry: The Next Generation, published by the University of Illinois Press in 2004. Her poems have appeared in Kenyon Review, American Poetry Review, POETRY, the Believer, New England Review, VQR, The Nation, New Republic, The Washington Post, Best American Poetry, and elsewhere. She lives in Southern California with her family and her wiener dog, Mustard, and works in business.

—Colin Winnette

COLIN WINNETTE: Victoria! You’re going against the grain here. You’ve recommended two books. And, since they’re new books, it’s safe-ish to guess you hadn’t read them when you recommended them. What motivated this recommendation? Are you messing with me?

VICTORIA CHANG: I can’t help but go against the grain, I suppose it is in my fabric to be a rule-breaker. And yes, I thought I would make you do some work and read them along with me. Plus don’t you think it’s more fun this way? We have no idea what we are going to say or if we will even like these books!

CW: I do think it’s fun this way. It created an odd tension between the two books I don’t think would otherwise have been there. Do you often read multiple new books at once? Do things get mixed up?

VC: I am always reading, always, and tons of things at once. I wouldn’t say I’m a voracious reader, though. I never finish books that fast, because I’m always reading so many things at once. I dip in, dip out, dip back in, sometimes never dip back in… I think my brain is full of collisions and that’s how I like to read and process information. I’m always comparing things and I think I do that subconsciously when I’m reading books of poetry.

CW: These are both Wave Books. What’s your relationship to Wave? Are they one of your go-to presses? Or are Wenderoth and Zucker go-to poets?

VC: Beyond submitting to Wave Books once (and being rejected) and having read with Matthew Zapruder once (at the Twitter headquarters of all places!), I have no relationship to Wave. I can’t decide if I like their sparse anti-covers though, but otherwise, it was random as I just wanted to read those two books by poets I admire by a press I really like watching.

CW: Wave books are very modest in appearance, it’s true. It’s like having a small stack of napkins on your shelf.

VC: Yes, napkins, definitely. It’s a very interesting design method because while everyone else is trying to draw attention to themselves with the spine, with the cover, Wave is saying, “don’t look at me, just read the work.” And they save money that way too probably. Smart.

CW: Would it be useful to talk about these two books in contrast to one another? They felt wildly different, at least formally and tonally. Or should we avoid thinking comparatively?

VC: I think comparatively would be interesting, but I wonder if talking about how their new work might compare to their older work would be really fascinating. For Wenderoth’s book, I had such a hard time getting Letters to Wendy’s out of my head because it was/is such a brilliant book and unfortunately, everything in my mind, will pale in comparison. I think this new work was weaker because it just has to be, but I think that Wenderoth excels at the prose form. In fact, when he tries to write shorter poems with line breaks, the form seems to really limit him and the writing sometimes veers towards triteness. His strength is the long prose line that allows him to be free in thought. Tautness does not seem to suit him. I feel like he fails when he is trying to be Poetic. He succeeds when he is just Wenderoth, if that makes sense.

What I love about Zucker is her ability to capture the uncomfortable feelings that float in and out of our daily mundane lives and those uncomfortable aspects of relationships and families. I particularly liked the dialogue in this new book. What’s also interesting about Zucker is how she plays around with autobiography in the first section of the book, but is coy about it, calling her husband, “the husband” and referring to the main character in third person. It’s a sneaky way of slipping away from autobiography but being autobiographical at the same time. Like Wenderoth, I think prose is the form that seems to best suit her work, but in contrast to Wenderoth, she stays true to prose and I think it’s quite canny that she can create so much tension with the slack lines of prose.

Zucker’s book has multiple sections and the themes in the section, pedestrians, are familiar ones—lacking time as a parent, getting interrupted by children, how women can’t write epics because they are interrupted, etc. She also has a sequence of dream poems, which I personally think are always hard to write (not another dream poem), and I wished hers were a little stranger. I’m not sure this book is a huge departure for Zucker, particularly in terms of theme and content, but she seems to be trying to move in different directions and simultaneously shackled by her own obsessions.

CW: For Wenderoth, I wonder if it’s a curse to have written such a singular and strong book early on… Are any of your books yardsticks for you? I’m asking personally (is there a book by which you measure all other work you make), but if you feel like readers perceive any of your books this way, I’d be interested to know.

VC: Yes, I’ve often thought about this. There are so many writers who are able to achieve that level of greatness early on because they are so gifted, like Wenderoth, like Richard Siken, like Ilya Kaminsky, etc. I too wonder if that might be a hard thing because how often do people get struck by lightning?

Our lives are short and everything sort of regresses to the mean. Are all subsequent books going to be a disappointment to readers? It might not even be a first book, for example, but a second book or fourth book. Ben Lerner’s Angle of Yaw is that way to me—while everything he has written is brilliant and he is clearly brilliant, I will always have a greater affection for that book as a reader. As a writer, do you want to go out strong and be well received or go slow and steady and improve slowly?

For me personally, I’m not sure. I question my own talent and ability to make creative work every single day and I am not exaggerating about this. I’m still not sure exactly what my own role is in the world of poetry yet. Am I stronger as a creator or an enabler? I guess this is the writer versus editor question people always say—are editors always weaker writers and better editors? My favorite book I have written is my most recent, The Boss, probably because it is the most recent. I have no idea if I will ever write another poetry book again and I will use The Boss as my measure of whether I should publish a future book—that is, if I feel the future book is weaker than The Boss, I won’t even send it out. Only if I feel it is stronger, will I even bother.

CW: The Boss is excellent. And, in some ways, it sits well with the two books under discussion. At least as far as the kind of humor you’re all interested in and great at employing to powerful effect. The three of you are very funny, and humor seems like an essential, or at least useful or delightful, part of poetry.

VC: I am often told in real life I am very “funny,” and I don’t actually know if it’s that I’m funny or that I am cursed with having a ridiculously frank mother who unfortunately also has absolutely NO filter. I think my way of being “funny” is just saying things that people think but have learned not to say, whereas, I haven’t learned not to say them. What’s odd about poetry is that it can be so dark and so funny at the same time. I think I love humor in poetry, but not that slapstick cheap easy humor, but that uncomfortable, “did she say that out loud?” kind of humor. It might actually be a generation X kind of humor since I believe Wenderoth, Zucker, and I are all about the same age more or less. I still can’t stop laughing at the beaver poem in Wenderoth’s Letters to Wendy’s—everytime I think of it, I start laughing. It’s that weird quirky sarcastic humor I love the most. People who are too uptight make me nervous.

CW: I think it’s sometime more than just a lack of filter. There’s an attraction to emotional clusters or hypocrisies or awkwardness. A desire to expose something or point at something that’s already poking out.

It’s partly the strength (and poignancy) of Wenderoth’s sarcasm in past works that makes me wonder if some of the poems in the new book are meant to fail. Or, more specifically, to say, can you feel how uncomfortable this is? It’s a way of activating the reader, demanding we be more present. Sort of like a problem kid who doesn’t care if he’s getting good attention or bad attention, only that he’s making us feel something. I don’t think we’re meant to get lost in these poems.

VC: It’s odd because I almost had a feeling that he put everything in there and didn’t care if the poems “failed” or not or were cliched or not. I don’t know if that’s true or not, but his book seemed more arbitrary in shape and form and order, as if he just doesn’t care anymore. There’s a slackness in the book that I don’t know whether it was intentional or not. I can feel the odd tension the poet feels towards his own position in academia and in truth, coming from Letters to Wendy’s to a tenured position in a university might be a strange experience. Sometimes I feel a little self-hatred in the speaker.

CW: Oh yeah, the book felt angry to me, at times. Or…cranky. But it’s also playful. I think the kind of grab bag quality the book has is part of what made me think my feelings of discomfort were there by design. Or that, rather than trying to put together something seamless, Wenderoth was trying to make something a little rougher, a little disjointed. To me, it felt more defiant than apathetic.

Zucker also does a lot to undermine her own wit, or complicate it with self-doubt or reservation. The voice in a lot her poems is strong, but unsure of itself, or too smart not to call itself into question. If Wenderoth is self-hating, what is Zucker?

VC: Zucker is the epitome of the modern woman—filled with existential anxiety, stress, uncertainty, and ambivalence. I love her and can identify with her in many ways, but she is way more candid than I am or would ever be comfortable being.

CW: It’s an unanswerable question maybe, but I wonder how crafted the actual digressions/associations are. For example, in a poem like “the meanest thing i ever said,” the list of activities, her illness, the movie she’s watching, the book she’s reading, the things she’s noticing, all accumulate and feel poetically right, but also realistic. Every disparate thing connects in some way that feels emotionally or intellectually right. So it feels crafted, on the one hand. But I can just as easily picture Zucker doing these things, or a lot of people doing these things, then sitting down to write a poem about the last few weeks and realizing, oh, shit, look at how all sort of brilliantly this all sits together.

VC: I sometimes wonder about Zucker and craft—I imagine she, like most poets, goes through her poems line by line, word by word, period by period and labors over them. She seems rather obsessive. But oddly, a lot of her work, like you are saying, seems very loose and almost stream of consciousness. It’s like you’re sitting at lunch with her in New York, there’s all this noise around you, and she’s dumping all of her daily problems on you, and you just want to get up and get a danish but you can’t because she just keeps on going and keeps you mesmerized. I think, though, that’s the trick of work that is good—it often makes the reader think, “Hey, I can do that too!” And as we all know, writing isn’t very easy. How many aspiring novelists do you meet a day? Everytime I read a children’s book, I think, “That’s it?” But every word is labored over so that it seems easy, but I think it’s really not.

CW: If you’re at lunch in NYC with Zucker, where are you with Wenderoth?

VC: In his bathroom watching him do unspeakable things with little plastic toys.

CW: Can you leave us with a representative sample from each, and a few thoughts on the sample?

VC: I liked “How to write post-eidetic poetry” by Wenderoth, which might as well be in prose form, but something about this weird “how to” poem just kept my attention as a reader—to the point, I was actually paying attention and visualizing this mosquito being cinched.

How to Write Post-eidetic Poetry

What you do is you take some dental floss

(well, wait—

first I should say that there is a mosquito on your leg,

and it is biting you)—

waxed or unwaxed, it doesn’t matter—

and you gently loop the floss

around the mosquito’s abdomen

(preferably between abdominal segment

one and abdominal segment

two).

Then you gently knot it—

and gently is really the key here—

if you make it too tight,

you may tear away the entire body

from the head and wings.

So be gentle,

and gently knot it …

and then gently …

gently …

pull …

If you are successful,

the mosquito will no longer be biting you,

and its stinger will not be lodged in your leg,

which means that your wound won’t itch as much—

won’t even be a wound, really.

Your success, however, leaves you with a problem.

You may not be able, that is, to untie the floss …

without hastening the mosquito’s death.

And you can’t just leave it on …

because what kind of life

could a mosquito cinched in floss

lead?

Would he even be able to fly?

The only way to really answer that question

is to take the floss-cinched mosquito

and go jump off a cliff.

If the mosquito is able to fly, you will know.

Here’s an example of Zucker’s work—not my favorite necessarily, but I thought her use of dialogue in the book was interesting and was successful in capturing real searing human emotions:

“I’m not angry,” she says.

“That’s the first nice thing you’ve said all day,” she says.

“I am listening,” he says.

“When you ask me what’s wrong, that’s what’s wrong,” he says.

“I don’t care if you write a children’s book,” he says.

“Don’t laugh at me,” she says.

“I was trying to help you,” he says.

“Stop talking,” say the children.

Colin Winnette’s fourth book, Coyote, (Winner of Les Figues Press’s NOS Book Contest), will be released in late 2014. His next novel, Haints Stay: A Western, will be released by Two Dollar Radio in 2015. A full list of interviews from this series can be found at colinwinnette.net.