A Conversation with Andrew Durbin and Ben Fama, and an Erasure Poem by Dorothea Lasky

Over the course of a few days, I spoke with poets and Wonder editors Andrew Durbin and Ben Fama about poetry, surveillance, and the Internet on a Google Drive document. Dorothea Lasky then “censored” any unwanted text from the conversation to create an alternate version of the interview in the form of an original poem.

Durbin, Fama, and Lasky are all contributors to the collection Privacy Policy: The Anthology of Surveillance Poetics, a compilation of new poetic works on surveillance. The Google Drive privacy policy states that the worldwide license of any work produced using their services—including this interview—belongs to Google.

The interview is presented here, with Lasky’s poetic erasure below it.

—Andrew Ridker

I. A MODEST EXCESS OF CAPITAL

ANDREW RIDKER: I wanted to start out by thinking through a possible working definition of ‘surveillance poetics.’ Put most simply, it can encompass works of poetry written in response to America’s surveillance state, which opens up some interesting questions about the intersection of art and politics. But there are conceptual possibilities as well; given that the very idea of surveillance involves poetic techniques like repurposing language, observing/overhearing others, ‘keywords,’ etc., it seems that an institution like the NSA and a working poet have overlapping interests that could affect the artistic practice itself.

BEN FAMA: A form of surveillance-as-text I think of often is Rob Fitterman’s piece “Now We Are Friends.” It’s a sharp, funny look at how the subject being watched allows himself to be complicit in their own conscription. Rob follows what seems to be a random person—Ben Kessler, first reproducing his personal website copy and ‘about me’ as poetic language, then contacting him, explaining what he has been doing, and inviting him to engage in the content he has created. Rob will be discussing the project formally at the Kelly Writer’s House, and he asks Ben Kessler to attend. Ben responds, he won’t be in town, but he’d “love to see some details on the project it sounds fascinating. Feel free to ask any questions or whatnot.” This was in 2009. I think it would be different now.

ANDREW DURBIN: Surveillance has been a part of art practice since at least the mid-60s, but it’s become especially important since the internet introduced chat-rooms, webcams, and easily searchable records and social media. Similar to (and in response to) that documentary surveillance culture, the best work being made right now is oriented toward and relies on surveillance tactics. The poetry I am most interested in is usually embedded in other practices, in other media, in other methodologies (prose, visual work, music) that—again: like the NSA itself—surveys from a point of obscurity. While it’s pretty ridiculous to compare an art form to a pernicious instrument of our security state, I think it’s important to note that poetry does operate under many of the same, all-inclusive assumptions about what can be a subject (anything, that is), trawling and “witnessing” history and lives for “material” that can be arranged into a record.

AR: Both of your poems in Privacy Policy are long pieces written in prose. Andrew’s begins as a short story set at a dinner party with Katy Perry, and Ben’s as an essayistic rumination on real estate mogul Andre Balazs. I’m wondering about these choices, and if the pieces found their way to more surveillance-oriented topics (as they do later in the poems) or if you began with someone like Chelsea Manning in mind.

AD: About six months after Edward Snowden disclosed the existence of the NSA’s PRISM program, Katy Perry released her third album, Prism, that, naturally, made no (direct or indirect) reference to the NSA or surveillance. Since she had nothing to say about the NSA’s program, I wanted to impose a narrative on the album that would, so I decided to “reveal” that her Prism is secretly related to a surveillance program called DARK HORSE that tracks and intimidates celebrities in order to keep them “on-brand.” In the poem, the surveillance culture that I hint at extends into a real one, the present one, which likewise keeps all of us “on-brand” (or in line—or online, for that matter). I wanted to address, generally speaking, the “(and those we work with)” aspect of our culture that Google refers to in their disclaimer.

BF: Most of the indications that we are being surveilled appear through targeted ads, so Balazs’ empire seemed like a good starting point of my piece Conscripts of Modernity. Every morning for a year or two I received Gilt City’s newsletter (I still do), and through studying the things they were selling and the language they use to make their merchandise desirable, I was able to form a narrative about their clientele, which was decidedly not me, though I did purchase a thing or two.

The amount of things to pay for—dry bar visits, custom suits, organic towels, dinner for two including two drinks a piece, two appetizers and two entrees—in their slick mosaic newsletter, there is a glut in these so-called luxury buys for young-adults with a modest excess of capital. You can assume they have no children, they are sexually active, they take “Hamptons Fridays.” Michel Houellebecq says “To increase desires to an unbearable level while making the fulfillment of them more and more inaccessible: this was the single principle upon which Western Society was based.” Have you seen the Pornhub search terms that were being livestreamed awhile ago? I am at work so I shouldn’t search for it (oh dear…) but you can imagine.

As far as Chelsea Manning, a year or so ago I went to see Desaparecidos play, do you know that band? They put out a single record in 2001 and that’s it, but toured again recently because of the political climate. I went—admittedly—out of nostalgia, and to see what they were going to do. At the time Chelsea was living as Bradley Manning, and the band had a large protest flag draped over part of the stage, and Conor [Oberst] really went in describing how for so long (after 9/11) even political musicians weren’t really saying negative things about the country because it seemed in bad taste, and now the tide had changed. The whole tour seemed like a platform to support Manning and also build support against Sheriff Joe Arpaio. I felt “all in” after that.

II. NO POETRY WITHOUT A POLITICS

AR: And yet, neither of your pieces feel rabidly anti-surveillance or even anti-NSA. In fact, most of the poems in this book investigate, borrow from, and repurpose surveillance techniques but only a few feel truly angry or dissenting. I was relieved by this—the book is an inquiry into surveillance and the poetry, not the politics, always comes first for me—but I’m wondering where the anger is, in the poems and in the media. Is it because the consequences still belong for the most part to a hypothetical future? Or because regular citizens feel they don’t have anything to hide? Or do we just honestly prefer targeted advertising and leave it at that?

AD: There is no poetry without a politics, but I’m not interested in subtweeting the U.S. Senate. I think it makes sense that it’s hard to find the “anger” because very few people (poets or otherwise) know how to be angry at the situation. The people who are angry and who know what to do—and who are meaningfully combatting the situation—are currently locked in a Kentucky detention center or are hidden away in Moscow or are imprisoned in an embassy in London. All futures being hypothetical, what we have is a present that refuses to end, more or less controlled by the supremely wealthy, and so, from the politically and socially weak position of the poet, I want to creep into the atmosphere of that, reverse the trajectory of the disclosure by leaking myself into that world, fictionalizing its reality while it continues to fictionalize and distract us from ours. I often go back to Josef Kaplan’s interview with ArtTalks, which unfortunately only exists in excerpt on the Poetry Foundation’s blog. He says,

Poetry is maybe one way to talk about politics in interesting ways, to demonstrate a kind of political logic that people may not be ordinarily willing to formulate. The disconnect happens when people think that articulation translates into capability. And it’s unfortunate for poetry because that idea severely limits the kinds of articulations you might otherwise achieve without that expectation. Poetry itself doesn’t do shit. Which is why you can have things happen in poetry that would be horrifying or terrible if conceived of in spheres outside of poetry. Which is honestly the best part about poetry.

BF: A lot of my writing, including Conscripts of Modernity, is me coming to terms with the brutality of the world, not to transmute it, or make it acceptable, but instead to endure it without looking away. The “nothing to hide” argument takes a narrow idea of privacy (and perhaps life itself). Much worse than oversharing, the minutiae of life—and not just the boring stuff—are becoming voluntary disclosures, with all of the humiliation that comes with that. I am complicit. I am outraged. I am terrified by the horror.

AR: And speaking of this lack of outrage, you both participate heavily (and, at the risk of seeming obvious, willingly) in social media culture, both for personal and poetic purposes. We’ve seen a new kind of poetics emerge (in part around the internet-based alt lit community); a hyper-confessional kind of poetry that borrows from social media. Is that the crux of the matter, then? That we can’t be outraged at a culture we constantly participate in?

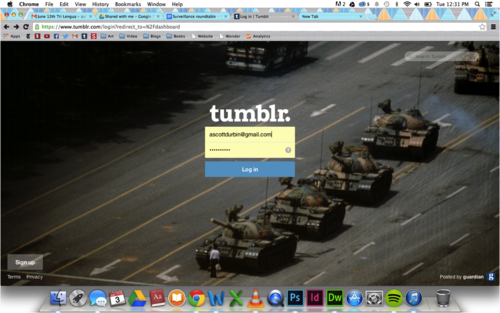

AD: For me, the biggest problem with social media is not its contribution to surveillance culture (though there’s that, of course), rather it’s its imperative to simplify: social relations, politics, language. For example, as I edited my responses to your questions, I re-logged onto my Tumblr after clearing my cookies. On the main login page I found what, at once, sums up what social media does to politics and what most irks me:

It memes them, which is precisely what governments would most like us to do. To reduce everything to the easiest possible bit of information—enough to make you feel, not enough to make you think. While poetry that addresses the meme (or that imitates the structure of the meme, as Edward Marshall Shenk’s work does) doesn’t necessarily recuperate political gestures made on social media, it complicates the social and aesthetic procedures of doing so by directly challenging the distribution network that makes them possible in the first place and remains, despite various assurances, deeply complicit with U.S. surveillance structures. And it does so at the most important site of contemporary social experience, where “liking” and “sharing” are consumer choices rather than functions of human interaction. That’s why I log on.

BF: I remember when social media used to be a playground, the way email used to be fun. Now it is an extension of the market, and I agree with Andrew’s reading of the “like” and “share” function as an extension of branding. The interest for me now are users who ironize these elements are part of their use. More optimistically, it is an essential way to aggregate the community, and keep up with current subjects, the “event” as it were. Social media flattens discourse, which is part of the allure, though it also can be generative, like much of what is in the recently published Yolo Pages. Trying to sustain conversations on these platforms, even when they start out well-meaning, usually leads to a dead end. We’ve all been in the thick of a Facebook comment section swamp.

***

The following is Dorothea Lasky’s erasure poem of the above.

AR: start through a definition of poetics. Work of poetry state, art and politics. possibilities as well; that the very idea repurposing language, hearing others, etc., the the art practice itself.

BF: the subject being watched allows himself follows what seems to be a random person—language, then contact, what he has been, inviting the content. the project formally, and he won’t be in town, but he’d “love to see some details on the project it sounds fascinating.” it would be different now.

AD: art practice the internet chat-rooms, webcams, and records. Similar to culture, the best work relies on tactics. The poetry surveys. While it’s pretty art, it’s important to note that poetry can be a subject (anything, that is), “material” arranged into a record.

AR: poems in Policy in prose. a story an essayistic rumination these choices, and if (as they do later in the poems) you began with mind.

AD: Perry naturally, made no (direct or indirect) reference. she had nothing to say secret related to a DARK HORSE. a real one, the present one, which likewise keeps all of us speaking, our culture refers to claim.

BF: Every morning for a year or two I received newsletter (I still do), the language they use to make desire, a narrative, decidedly not me. suits, towels, dinner, slick mosaic, a glut. children say, “To increase desire to base.” Have you seen Pornhub? (oh dear…) a year ago, do you know that band? a single political climate. the band a large protest over the stage, so long about the country in bad taste, now the tide. The whole platform to support and also build support. I felt “all” after that.

AR: few feel truly angry. an inquiry into politics, first—the anger. Is it the future? Or do we just prefer leave it at that?

AD: no politics, the “anger” how to be angry. people are angry. futures is a present that refuses to end, and the weak the poet, I want to creep into that world, I often go back to Art, which unfortunately only exists

Poetry politics people

Poetry itself doesn’t do shit.

BF: A lotis me coming to terms with the brutality of the world, to look away. “nothing” a narrow idea of life itself). not just the boring stuff—all of the humiliation.

AR: lack of outrage. Is that the crux of the matter, then? That we can’t constantly participate?

AD: I edit my responses your questions, I clear my cookies:

It memes—enough to make you feel, not enough to make you think. That’s why I log on.

BF: remember when play used to be fun. Now it is an extension of branding. me who ironize these elements an essential way to keep up with the Social, which is a dead end. We’ve all been in the thick of a swamp.

—Dorothea Lasky

Ben Fama is the author of the artist book Mall Witch, as well as several chapbooks and pamphlets. In 2015 Ugly Duckling Presse will publish Fantasy, his first full length book.

Dorothea Lasky, is the author of four full-length collections of poetry, including Rome (W.W. Norton, 2014) and Thunderbird (Wave Books, 2012).

Andrew Durbin is a poet and the author, most recently, of Mature Themes (Nightboat). He co-edits Wonder with Ben Fama.