A Review of Rachel and Miles X-Plain the X-Men by Stephen Burt

CENTRAL QUESTION: What can we learn from overhearing a long conversation about superhero comics?

PODCAST SITE: rachelandmiles.com/xmen

FAQs (PARTIAL LIST): “Where should I start?” (X-Men Season One or Giant-Size X-Men #1); “Can I be a guest or Emergency Backup Co-Host?” (no).

NON-AUDIO SIDELIGHTS MADE POSSIBLE BY CROWDFUNDING: video reviews of current titles; T-shirts that say “Magneto Made Some Valid Points”

BASE OF OPERATIONS: Portland, Oregon

OTHER COMICS PEOPLE BASED IN PORTLAND: Brian Michael Bendis; Joelle Jones; Jamie Rich; Sara Ryan; Craig Thompson; Douglas Wolk.

Here is one way to create a first-rate podcast. Pick something you know an awful lot about—and something your best friend, or life partner, knows well too. Your repartee will become the heart of the form. Pick a topic that some other people take seriously enough that they might want to hear about it for (say) half an hour, but not so seriously that they won’t want jokes. Make it a topic big enough that you can return to it again and again, without exhausting its devotees, no matter how narrow it seems to the rest of the world.

Then break that topic up into connected, potentially independent slices, like chapters in a continuing serial narrative, so that you can create running jokes, but newbies can enter at any point. Arrange for a signature opening. Use music (a theme song) and sound effects (reverb, say) lightly: do not overwhelm your speaking voice. Use copious notes and an outline to guide conversation. Show off the intimacy, and the informality, that fits the podcast form—but take advantage, too, of the way it gives you time to research and prepare. Put images and other extras on a Tumblr. The podcast should feel as if listeners were at home, or out to lunch, with the pair of you, hearing you argue congenially or egg each other on.

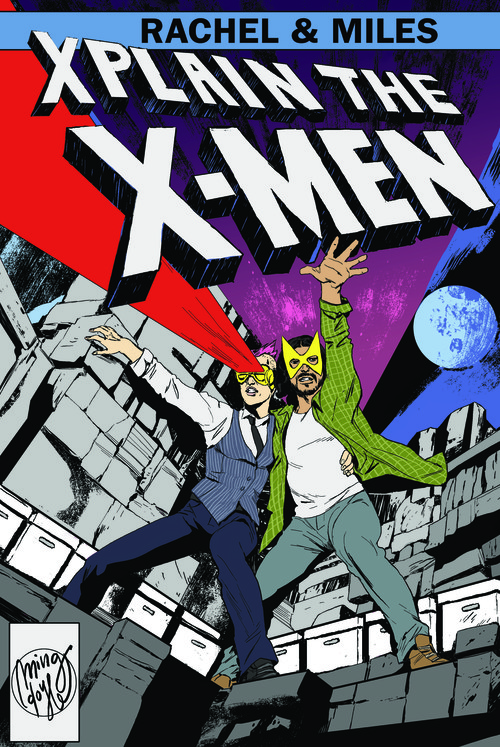

“Rachel & Miles” (their Twitter handle) are married, and both have worked in the comics industry; they began reading comics together in their teens, and speak with the speedy, grammatically correct, enthusiastic dialect of geek culture. They are the Hepburn and Grant of comics geeks: their sustained manner is reason enough to tune in.

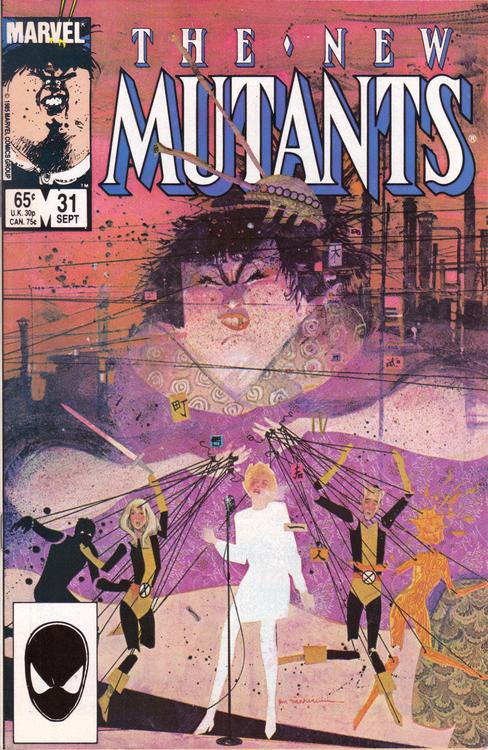

But it is not the only reason. “Rachel and Miles X-Plain the X-Men” started in April 2014. It has continued each week, sometimes with guest stars, interviews or digressions (about, for example, this year’s X-Men movie). Most episodes, though, explain a major storyline or development in the comics, proceeding chronologically from the 1960s issues on. Right now they are up around Uncanny X-Men #181 and New Mutants #17, in episode 30; at this rate they have years of weekly podcasts to go.

The X-Men are not just a handful of heroes in movies, but an almost unmanageably intricate tangle of mutant friends, lovers, enemies, mansions, islands, spaceships, uncles, granddaughters, graduate students, telepaths and sociopaths who have fought, made up, run away, formed new teams, build new cities on islands, and wrecked their Westchester County boarding school again and again, over thousands of issues of Marvel comics, all the way back to 1963.

No wonder they solicit explanation. Each week begins with a “cold open,” a Q&A that highlights the X-Universe’s ridiculous complexity: the character Cassandra Nova, for example, was “Professor X’s evil disembodied psychic twin; while they were gestating she tried to clone herself a body based on his, but Fetus X strangled her so she was born as nothing but a malevolent consciousness… Decades later Cassandra managed to produce an adult body which she used to unleash the Sentinels on Genosha, decimating the mutant population, then made her way back to the Xavier school, switched bodies with Professor X without anyone knowing, leaving him trapped in her body whose vocal chords she had severed” (all said very clearly and very, very fast). At the end of each opening, we hear an astonished, befuddled Miles ask, “Whaaat?” and we are off into the Dark Phoenix Saga or the story of the Shi’ar empire or Dracula or whatever else that week brings.

Rachel and Miles make good role models for people who want to explain almost anything—they repeat and recap details without condescension, they’re always having fun, and they never stick to plot summary. Instead they use the week’s storyline as a jumping-off point to discuss, for example, the working methods of one comics artist, the merits of third-as against first-person narration, the representation of Canada in Marvel comics (it is a very dangerous place), or the way life changes when you leave your teens.

The X-Men are mutants, quintessential outsiders, whose quarrels and love lives can have them behaving like teens even when they are supposed to be adults: even more than most superheroes, they serve as magnets for reader identification. Rachel sees a part of herself—as she says—in the stoic, and often unlucky, team leader Cyclops, wound tight, unable to let himself go. Miles hasn’t yet said what X-Man he resembles (I bet it’s the solicitious, loyal Nightcrawler) but he, too, can project himself both into the comics’ younger readers, and into the team. The duo’s sheer interest in these continuing characters, their level of engagement with artistic style (Paul Smith draws a great Storm: why?) sets a high bar for other kinds of art. How many people care about Caravaggio as deeply as Miles and Rachel care for Paul Smith?

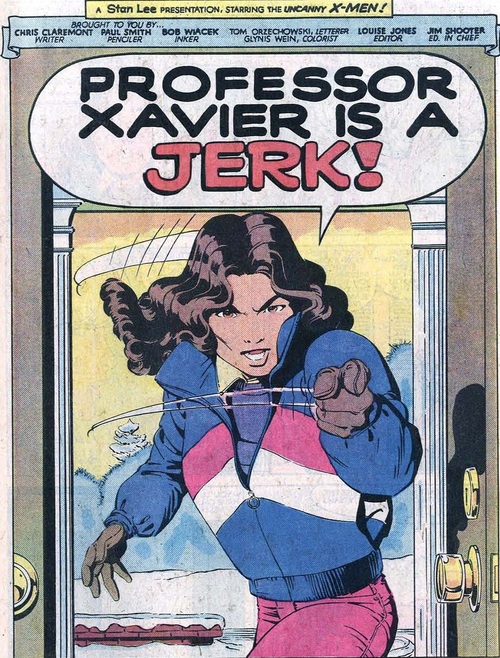

As Rachel and Miles point out in episode 8 (“What We Talk About When We Talk About Claremont”), the X-Men are the only mainstream superhero franchise thoroughly shaped, over decades, by one writer’s vision: Chris Claremont did not create the X-folks ex nihilo, but his scripts, between 1975 and 1991, made them most of what they are even today. That run—along with the characters’ palimpsest-like complexity—makes them uncommonly fit for sustained analysis. The X-Men have always been owned by a corporation, where many people (some of them real hacks) put issues together on tight deadlines: nobody should mistake God Loves, Man Kills for In Search of Lost Time. But the series did bring new depth, and new political savvy, to its genre: for example, in how Claremont learned to write women’s friendships, and how he used the character Ms. Marvel to attack what earlier, sexist scripts had done. Rachel and Miles lay out how and why.

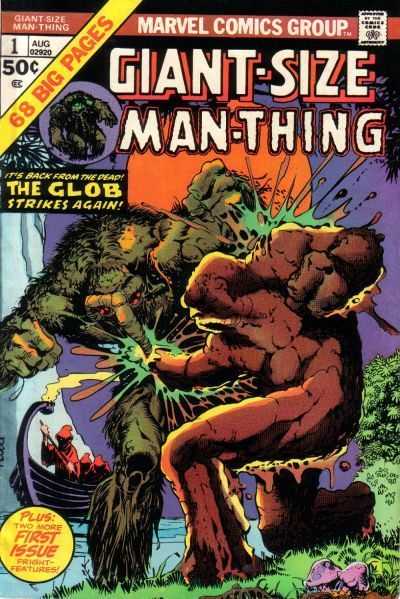

They also make jokes: the Shi’ar are “space-bird jerks”; the winged X-Man Angel’s only “job is to not get hit with things”; real wolverines are not wolves, but “stinky large weasels,” and Storm ought to whack Wolverine with a rolled-up newspaper when his berserker rage makes him rude. The pun-friendly podcasters mock everything that seems mockable, and they are happy to say where writers go wrong: did you know that Marvel once published a comic called Giant-Sized Man-Thing #1? Yet the Rachel and Miles podcast is an exemplary act of critical appreciation—one that everybody who likes superhero comics, and maybe everybody who has ever liked superhero comics (by the way, when did you stop liking them?), and maybe anyone who wants to assemble a podcast, would do well to hear.

Stephen Burt is a Contributing Reviewer of the Believer.