On Scriabin’s Piano Sonata No. 9, by Michael Peck

Before the outbreak of World War I, Russian composer Alexander Scriabin sketched out a monolithic orchestral piece to usher in the end of the world. Enigmatically called The Mysterium, the composition would feature flaming clouds and perfumes to enhance the catastrophic mood of the work, in addition to a massive light show. His welcoming in of the apocalypse, which would last seven days, was to be performed at the base of the Himalayas in a specially built amphitheater. Together, a great war and his music, he believed, would purify mankind and usher in a new age of wonderment. Scriabin’s initial compositions—preludes, nocturnes, mazurkas, his first piano sonatas—were greatly influenced by Chopin, albeit with snippets of the weird sonorities to come. Scriabin was drawn early into the superman philosophy of Nietzsche before turning to his own whipped-up version of eschatological aesthetics. While most composers have sought to represent ideas or soundscapes, Scriabin was convinced that his music would not only destroy the world, but also—once that was accomplished—go on to influence a bona fide utopia.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jeXJgjq-kbQ]

These chords of a dissolving world are rife in Scriabin’s tangle of Romanticism and the occult, and nowhere more tangibly than in his 9th Piano Sonata, the so-called “Black Mass” sonata (it wasn’t dubbed this by the composer, but he approved the subtitle nonetheless). Scriabin’s diabolism was already apparent—he refused to play his 6th Sonata publicly because he believed it to be “nightmarish, murky, unclean, and mischievous”—yet the 9th most clearly spells out his adherence to the occult. The sonata unwinds with a slow recursive theme in minor ninth intervals. Very soon it morphs into jarring arpeggios which quickly sublimate the ethereal quiet of the opening bars. Undulating between lyrical and combustible, the 9th is like a topsy-turvy gondola ride to the underworld. Tumbles of crazed trills dominate as the piece rushes to an orgiastic eruption of chromatic chords, leading to one of the darkest outbursts in classical music. Only then does the preluding theme return to wrap-up the sonata, quietly bringing the listener to Scriabin’s foreshadowing of some pre-post-prelapsarian cosmic order.

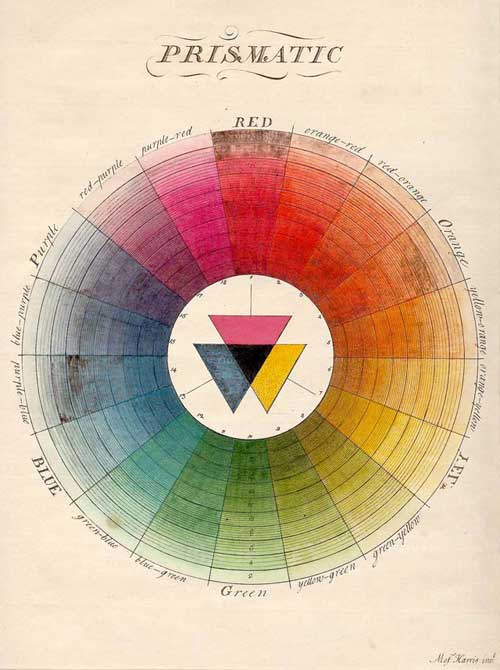

In the 9th Sonata and elsewhere the struggle between inner tranquility and outer turmoil is prevalent. Completed in 1913, the 9th shares with Scriabin’s other sonatas the absence of a key signature and his use of the “mystic chord”(C-Fsharp-Bflat-E-A-D) to augment his terra incognita musical landscape. Never explicitly atonal, Scriabin’s chromaticism toys with atonality, inverting classical music’s traditional progressions into a maelstrom of circular harmonics. Scriabin composed experiences rather than motivic ideas, ecstatic or corrosive moods rather than the usual variations-on-a-theme. He color-coordinated the moods of his orchestral pieces and sonatas with an apparatus called a “color organ”, which was maneuvered with pedals, as well as many colored lamps; his rigging of such devices and use of a colored-in circle of fifths based on Newton’s Opticks have led to associations with synesthesia, but were probably more suggestive of a case of metaphysics. Rachmaninov (a classmate of Scriabin’s) recalled that Scriabin and Rimsky-Korsakov agreed that D was a golden-brown, but that they disagreed on E-flat major—R-K came down in favor of a reddish-purple, while Scriabin thought it had to be more bluish. A few decades ahead of its time, Scriabin’s music was initially unwelcome in Russia, as it was considered “ultra-modernist.”

Had Aleister Crowley been an impressionist along the lines of Claude Debussy, steeped in Lovecraft and a premature fan of True Detective, his music may have sounded a little like Scriabin’s. His dogma was a holy trinity of Gnostic tenets and catastrophism, with a dash of color theory thrown in. Yet it was with Theosophy that the composer found a syncretic buffet of hermetic and proto-Christian notions that came close to approximating his own far-flung personal mysticism. Founded in 1875 in New York City, The Theosophical Society was the brainchild of Henry Steel Olcott, William Quan Judge and Blavatsky, the latter acting as the society’s official theorist and mystic extraordinaire. Its epistemology, which must have instantly sated Scriabin’s quest for syntheses, was a fusion of Eastern spirituality and the ancient mysteries and rites of the West, incorporating all things arcane, from Swedenborg to the heresies of the medieval Cathars. With Theosophy, Scriabin found the incompatibilities of his psychic idiom now compatible with an actual organization within which to communicate his artful transcendence of nature. Disruption and mystic tranquility are mainstays of his middle and late compositions, mirroring Blavatksy’s darkness-vs-light theories. Scriabin’s vision of armageddon was the start of a cathartic rebirth for mankind, and, if the music is any indication, a melodious one as well.

More than just a tone poem or soundscape, the 9th Sonata is a conflagration. It is a glimpse into the mind of a man who one-upped John Lennon by noting in his diary, “I am God”, using the date of his birth—Christmas Day of 1871— to prove his assertion. His musical occultism, like his personal occultism, is one of vast extremes: crazed and grotesque, with sinister marches, disturbing trills and an almost jazzy chord structure that’s as distinctive as it is diabolic. The very next moment, however, his music segues into simplicity and gentleness, seemingly culled from disintegration, culminating “with a whimper.” For a horrifying experience, no performance equals that of Vladimir Horowitz, whose stilted phrasing is perfectly fitted to Scriabin’s ambiguous theology, moving from innocence to upheaval in a way that sounds like some esoteric soundtrack to the universe’s origins, dissolution and edenic reconstruction. Although The Mysterium, his monumental paean to the world’s demolition, was left unfinished, Scriabin’s brand of mysticism—an eccentric blend of Theosophy and auto-messianism—converges in the 9th Sonata with a vengeance unparalleled.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ENxotmXmvGw]

Colorwheel from blog.colourstudio.com