An Interview with Claudia Rankine

“The struggle of man against power,” wrote Milan Kundera, “is the struggle of memory against forgetting.” This statement points towards one of the central themes that unfolds in Claudia Rankine’s new volume of poetry, Citizen: An American Lyric.

Citizen, which was short-listed for the National Book Award, and has received wide critical and popular acclaim, is a book about racism and micro-aggressions, about our private selves, our public selves, our “self selves”, and our “historical selves”, and about what it means to be an American citizen today. The book meets you “when you are alone and too tired even to turn on any of your devices,” and forces you to observe: what’s outside the window, what’s on the television, what’s at the margins of the painting, and what’s happening—whether you admit it or not—at the margins of your mind. As Hilton Als puts it, “Citizen comes to you like doom.”

Switching between forms—verse, essays, second person narratives, images, and collages of quotation from other texts—Rankine is as comfortable inhabiting the most fleeting and private of emotions as she is addressing an indifferent American reality. Indeed, each form allows her to reveal new aspects of her subject matter. Her essays open up her images, and her images open her essays.

I met Professor Rankine (who teaches English at Pomona College) at her house in Claremont, California over Thanksgiving break. She invited me, an unknown student from a different college, over for Thanksgiving dinner, and then spoke to me for an hour two days later. Along with seriousness and outrage, I detected hope in her voice. Her answers, like her book, never shy away from the harsh truth. But one senses that she believes, that she actually imagines a better reality.

—Ratik Asokan

I. PAST THE BEAUTY AND INTO THE POWER

THE BELIEVER: Did you always know the book would take such a hybrid form?

CLAUDIA RANKINE: No. When I first started working on Citizen, I had no idea what form it would take. I didn’t know that the various approaches would end up in the same book. For example, I wrote the essay on Serena Williams because I was thinking about something someone said about Serena. It didn’t initially occur to me that the piece would be in the book.

It wasn’t as if I began on page 1 and ended on page 159. It came together. It’s one of those things: when you’re working on something over a long period of time, your mind—at least the way I work—your mind is probing your subject in different ways all over the place. At a certain point, you sit down and pull it together.

BLVR: So did the images provoke you into writing? The reader never stops to question whether the text or image came first.

CR: Well, I think that once I began to put the book together everything that is of interest to me became a part of the book’s conversation. I would think about the essay, as an example, and the images that open out the essay in certain ways, or images that create a surprise moment in the essay came to mind. It’s almost like working with building blocks. You begin to think, oh, I was really interested in that image by Nick Cave and actually it would work right here. Or, in a call and response way, I would write something and it was as if Nick Cave’s piece spoke back.

BLVR: You have said that Nick Cave’s “Soundsuits initially struck me as wishful thinking, they were fanciful garbs, but reading Robin D.G. Kelley, specifically Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination, which makes the argument that change comes out of the surreal, and that we have to find pathways there, helped me to value the stealth of Cave’s suits.”

CR: Well to be honest, initially I saw Cave’s Soundsuits as a type of beautiful, amazing escapism. I valued them as an experience without understanding how they were positioned historically. That was until I allowed myself to embrace the idea that the surreal allows the mind to kind of jump the impasse. If a breach happens because some moment of injustice creates a kind of incoherence, then you have to create a pathway out of that. So maybe it will look like an escapist moment, a surrealist moment, but in fact it’s just a pathway. I became very interested in Cave’s work when I could see past the beauty and into the power.

Soundsuit, Nick Cave. Photo by James Prinz. Courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Soundsuit, Nick Cave. Photo by James Prinz. Courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

BLVR: Could you speak a little about the image?

CR: I felt that much of the criticism that was hurled at Serena Williams had to do with her appearance. Cave’s soundsuit has this exquisite, flowery crochet back…but in front is a black netting. If the person wearing this suit stood up, what you would see is a dark black covering. But if she bent over, than you got this kind of beautiful color that was acceptable, even dazzling, to whoever was looking. I thought this enacted the public expectations for Serena, the desire for her to look a certain way. And it’s not just about her skin color. It’s also about her form of dress, which I think she chooses so as to exist in the margin, to quote bell hooks.

BLVR: After the Wozniacki incident (in 2012, Caroline Wozniacki imitated Serena Williams by stuffing her top and shorts with towels, in an exhibition match) Serena actually released a statement saying that she wasn’t personally offended, and that Wozniacki and she were friends. However, she added that Wozniacki might want to reconsider her actions if other people were offended.

CR: At that point Serena doesn’t have to speak to the display. Turns out she and Wozniacki are friends, but that’s beside the point. In my essay it says that Serena didn’t say anything when Wozniacki mimicked her. But CNN did. They asked if it’s racist for a white woman to take on the body posture of a black woman in a mocking fashion. The other thing about Wozniacki’s performance, is that whether or not she realizes it, it steps into the Venus Hottentot debate. There’s a history (before Serena), which is being played out, relating in part to Saartjie Baartman and then moving forward. One has the sense that Wozniacki has no idea how slavery, colonialism, and on and on creates the white imagination that allows her to feel that Serena’s body is something to be mocked. On a certain level it’s no longer about her relationship with Serena Williams.

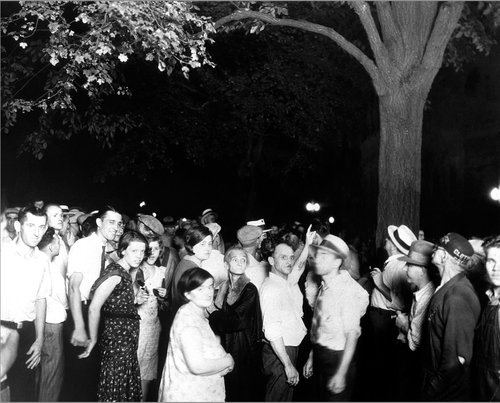

Public Lynching Date: August 30, 1930. From the Hulton Archives. Courtesy Getty Images (Image alteration with permission: John Lucas)

Public Lynching Date: August 30, 1930. From the Hulton Archives. Courtesy Getty Images (Image alteration with permission: John Lucas)

BLVR: And the Wozniacki video—the way the camera pans across the audience to catch their amused reactions—reminded me of a watered down version of your reworked lynch mob photo.

CR: Right. The idea of redirecting the gaze on the spectator, of being interested in liberal subjectivity, of observing the people who would normally not claim racism as their thing is of interest to me. The cameraperson was clearly thinking the same thing. These people, with the benefit of the doubt, are not supremacists and yet they will step into this moment, find it funny, and in doing so, they willingly disconnect themselves from the histories and realities of black people and the treatment of black and brown people in this country.

II. “ARTISTS TEACH WRITERS HOW TO SEE.“

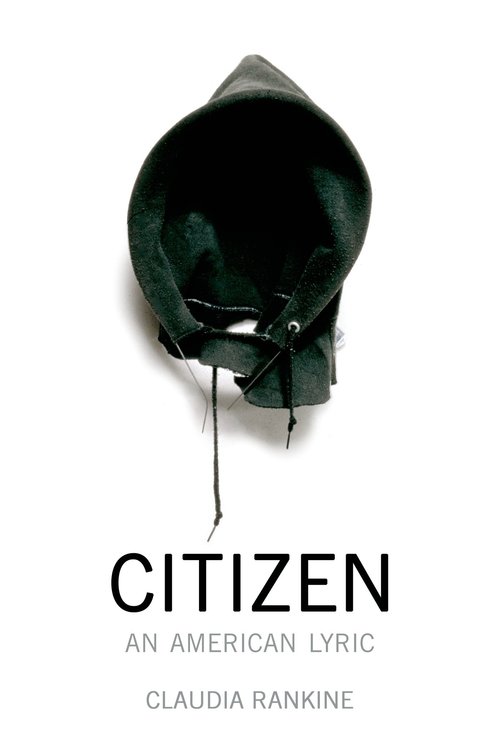

BLVR: I wanted to talk about Citizen’s cover image. It drew wild associations from me—slavery to the grim reaper. Where exactly does it come from?

CR: It’s a hoodie that the conceptual artist David Hammons made in 1993, two years after the Rodney King beating. He cut off (it almost looks like he hacked off) the rest of the sweatshirt and hung it in the gallery. It has remained timeless and relevant. What happened with Trayvon Martin, the sense that he brought on his own death by dressing like a hood, made many believe Hammons made the piece in response to his murder. But Hammons knew or knows already.

Little Girl, Kate Clark. Infant caribou hide, foam, clay, pins, thread, rubber eyes. 15 x 28 x 19”. Courtesy the artist.

BLVR: The book’s second image is Kate Clark’s Little Girl, a sculpture of a deer with a human face, made with real caribou hide. You place the image alongside a narrative of a psychiatrist who takes her African-American client to be a dangerous trespasser. When the psychiatrist yells at her, the client feels that “It’s as if a wounded Doberman pinscher or a German shepherd has gained the power of speech.”

Of all of Clark’s human-animal figures, Little Girl seemed to me both the saddest and the wisest, and perhaps saddest because she’s the wisest. Whom does she represent in the narrative?

CR: I was very moved by Kate Clark’s sculpture as well—partly because the deer body is something that’s hunted. I told her that I’d love to use it in the book and she said, well, why don’t we make a new one for your book? She created a new one, but it wasn’t the same. So I ended up using Little Girl.

It has a type of melancholy to it, a sadness that could go either way. In the accompanying narrative, it felt to me that the woman that was seeking help was actually being attacked by the psychiatrist, who obviously had her own projections around blackness, and was so frightened by it that she was willing to hurt anybody in order to protect herself from whatever incident was informing her imagination, whatever was haunting her. The image of this deer-like, mythic creature felt as if it was flipping back and forth between the two women.

BLVR: What about Mel Chin’s VOLUME X No. 5 Black Angel?

CR: Mel Chin did a project where he took all the images from an encyclopedia set and made collages out of them. VOLUME X No. 5 Black Angel seemed to me, whether or not this was his intention, a representation of the black body’s positioning within a canonical structure.

BLVR: And Carrie Mae Weems’ Blue Black Boy?

CR: I was really interested in echoing Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue throughout the text. I wanted it to rinse the world of Citizen in a certain way. Carrie Mae Weems’ image is part of a series that is also thinking about different skin tones. For me her image, the triptych, became a study of the weight the black male figure carries, given the fact that they are targeted by the police, and are constantly in danger of being misread in public spaces. Sometimes the art pieces I gravitate toward speak to me in terms of narrative, at other times they speak to me in terms of mood.

BLVR: You discuss how Glen Ligon turned Zora Neale Hurston’s line, “I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background,” into an abstraction by putting it in his painting. Do you like what he did with his painting?

CR: Both pieces by Ligon in the work fade out or blend into an abstracted reality. Hurston’s line becomes illegible as you move down the piece, it descends into the ordinary day-to-day-ness of its truth. I was really interested in the way micro-aggressions are part of the quotidian negotiating our lives.

Ligon’s piece shows how reality has absorbed Hurston’s words. Her words are so present that they don’t need to be apparent.

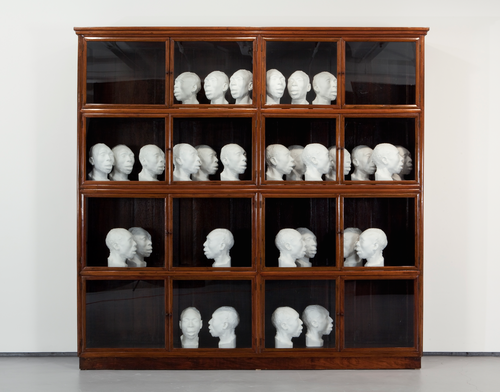

Cerebral Caverns. Radcliffe Bailey, 2011. Wood, glass, and 30 plaster heads. 97 x 100 x 60″. ©Radcliffe Bailey. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Cerebral Caverns. Radcliffe Bailey, 2011. Wood, glass, and 30 plaster heads. 97 x 100 x 60″. ©Radcliffe Bailey. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

BLVR: What attracted you to Radcliffe Bailey’s Cerebral Caverns?

CR: There’s a line in Citizen that says the past has “turned [our] flesh into its own cupboards.” We have had to hold the history of this violence in our bodies for centuries. I had that line in my head when I saw Bailey’s piece, which both reflected the line back to me, as well as also representing the way bodies are stacked on top of one another in slave ships. The heads are speaking to each other, almost as if they are asking the question, “Did he just say that?” “Did I just hear what I think I heard?” I am projecting wildly but the piece is so open it allows that. I’m not sure what Bailey intended, but those were some of the things I started to associate with when I saw his work.

BLVR: Have you always been interested in paintings and sculptures?

CR: Baldwin said that artists teach writers how to see. I spend a lot of time observing people. I find people fascinating.

III. EMOTION THAT DOESN’T BELONG TO YOU.

BLVR: In Notes of a Native Son, Baldwin writes, “It is only in his music, which Americans are able to admire because a protective sentimentality limits their understanding of it, that the Negro in America has been able to tell his story.”

This seems to hold true even today. It surprised me that there was no music in Citizen. What are your thoughts on the way African-American experience is represented in popular music today?

CR: It’s true that the book doesn’t go into areas of contemporary music. It does reference Miles Davis, Kind Of Blue, which I sort of riff on throughout. I didn’t address music partly because I am more a visual arts person. They is an automatic association between blackness and music that I was less interested in as a trope for this book.

BLVR: Do you think that popular music can bring about meaningful social change?

CR: I definitely think so. I think music, like writing, can be a mirror. Can turn back onto the listener, the viewer, the reader, an experience that they know but they don’t know. That they feel but they can’t articulate. Obviously listening to Jay-Z on a college campus is different from listening to Jay-Z in Brooklyn. The music does something else for a particular people, and you might not know who those people are—but it does something else.

BLVR: Section VI is comprised of scripts for ‘situation videos,’ some of which are online. Situation No. 5, In Memory of Trayvon Martin, has So What playing in the background. Situation No. 6, Stop-and-Frisk,was nothing like what I expected it to be. It’s just a video of boys shopping, but the text is about a case of racial profiling. I kept waiting for something horrible to happen.

CR: That feeling of dread is what we wanted to communicate. Black men are attempting to go about their lives, buying a T-shirt or whatever, but at any moment something could happen, at any moment the police could pull up and decide destiny, at any moment you could be confused with somebody else. And that would be that. I felt that the burden of expectation would carry the feeling throughout without anything having to happen.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0xx1dwFxAv0]

BLVR: There’s a situation video based on Zidane’s World Cup head-butt. Most people sided with Zidane on the issue. But not so many defended Serena during her incidents. Why do you think that is?

CR: Well, it’s a mix of sexism and racism in this case. Men are allowed to retaliate and get angry; women aren’t. The response to Williams is compounded by the ‘angry black woman’ trope. People expect black women to be angry, irrationally so, without reason. They think we are animals and we go around like the Wild Things. Viewers respond as if there’s nothing provoking her anger. Their response can be reduced to she is just “being black.” When Serena loses her temper in the face of racist actions from others, it seems as if viewers think, there it is, there is that angry black woman.

BLVR: Do you think that sportsmen/sportswomen, especially those belonging to minority groups, have an obligation to be role models?

CR: You know, I don’t really agree with the role model thing. People are always saying that athletes shouldn’t do X or Y because they are role models. You become a role model because of what you do as a person. There’s a certain point where being a role model might come from standing up for yourself and getting rid of emotion that doesn’t belong to you, emotion that is being brought on because of racist actions of others. Only another racist would think it was bad behavior to respond to that kind of onslaught. If you are going to suppress your emotions in order to be a “model citizen”. I’m not sure if I’m interested in that.

BLVR: You mention how commentators later lauded Serena for growing up, “as if responding to the injustice of racism is childish and her previous demonstration of emotion were free floating and detached from any external actions by others.” The question of emotion, that is, what to do with emotion, seems to lie at the heart of your book.

CR: Right. Who’s to say what is a reasonable reaction to have and what is not? Especially when this criticism is coming from a person who is herself/himself not experiencing a build-up of erasure or the reverberation of racist aggression. The commentator who accused Serena of being immature is a white male. What does he know about what it feels like to have a constant build-up of projections and stereotypes being hurled at you? He has no idea. It’s easy for him to say, “Just ignore it.”

We will always fail each other. That goes without saying. The question is, what happens next? If failing is then countered with the question, “What’s wrong with you?”, then that’s a problem. If you make a mistake, then you should own that mistake. You should admit, “What I said was racist and that is really unacceptable.” You don’t say, “Get a sense of humor.” And you don’t say, “Grow up.” The problem is not only that the blow is dealt. The blow is dealt, and then the brown or black person is told that the blow wasn’t a blow.

BLVR: But if I admit to being racist, what does that say about me?

CR: If you admit to being racist, it says you acknowledge that you are being driven by projections and stereotypes that were formed in the creation of our country. Racism is deeply rooted in America, as President Obama points out, and some bodies continue to bear the lash of that and others perpetuate it. Until we admit to this, nothing will change or as Baldwin says, “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

BLVR: Citizen doesn’t just shake you up. Sometimes it educates you. I hadn’t heard of many of the stories here.

CR: Well, part of my process is archival. I am invested in keeping present the forgotten bodies. This aspect of working, where you bring the dead forward, is crucial to my process. There are all these men and women who have been killed, like James Craig Anderson, that make the news for a day or two and many people haven’t heard about them. You ask them, and they just haven’t heard. When these killings are forgotten, people then begin to say things like, ‘that was from Jim Crow,’ ‘that was from the 50s,’ ‘this type of thing doesn’t happen anymore,’ ‘you have to admit things are better,’ ‘things have changed so much.’ No—this happened last summer, this happened this summer, this happened in August. I think it is necessary to keep reality present, we all need to be facing the same way; we need to be negotiating the same facts. Then together we can have a sense of how racism stays present, how it stays vigilant, focused on its target.

BLVR: Do you think that public discourse today has the language to really talk about racism? To talk about it in a way that doesn’t make racism its own issue, one distinct from the rest of life?

CR: I don’t know if you have read Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow. One of the book’s projects is to make it clear the ways in which racism and Jim Crow laws have been built into the system, so that the mechanisms of warehousing black bodies, imprisoning them and raining down injustice on them, continue. That book is very important to me. You know one in three black men spend time in prison, but you don’t know the justice system needs that to happen, ensures that it happens.

IV. TO LOCATE YOUR HUMANITY

BLVR: A central theme of this book, I thought, was that of having answers but not knowing what the questions were. Your New Yorker interview ended with Alexandra Schwartz asking you: “I’m not exactly sure how to phrase this, but is there a question I should be asking? What is the question that isn’t being voiced?” which I thought was just perfect. Would you agree that part of your objective with Citizen was to create a discourse that allowed us to engage with overlooked issues?

CR: I think that one of the positions we have taken around the question of race, is that we already know. We know. We know. We know. And so we don’t need to look at it again. And yet everybody is still upset. Everybody is still being driven by their outrageous imagination to the point of killing people because they feel that a black man in front of them is a demon, or the Incredible Hulk. A twelve-year-old is still being shot to death and described as a twenty-year-old with a gun. Obviously in such cases, the white imagination has taken over reality. If the police in these cases would begin to ask why that happens, to question where those perceptions are coming from, since the perceptions have nothing to do with the person standing in front of them, then maybe we could back up, and look at white subjectivity, and the types of things that whiteness fears. Things that have nothing to do with the brown or black body; things that have everything to do with white privilege, wanting to hold on to white privilege.

BLVR: One of the characters in Citizen says: “A friend argues that Americans battle between the ‘historical self’ and the ‘self self’. By this she means you mostly interact as friends with mutual interest, and, for the most part, compatible personalities; however sometimes your historical selves, her white self and your black self, or your white self and her black self, arrive with full force of your American positioning.”

We buy into such myths every day.

CR: I want to believe that in any relational moment a person understands that the other person in front of them is just another human being. We know that if you shoot that person, that person is going to die. If you shoot me I’m going to die. We are the same in this way. And yet, when push comes to shove, people are still grabbing their purses, still running away, still perceiving danger, and shooting kids with toys in their hands, and saying, you know, that they felt legitimately threatened. If that’s the case, then I think the person in front of them is no longer a person, that person is some kind of projected, embodied stereotype. The person in front of them has moved into the space of the stereotypes created by the white imagination, just by virtue of crossing paths with their white imagination. If the white person developed a relationship with the black or brown person before them, then the white person gifts the black or brown person the exceptional narrative. I am suddenly not like other blacks. Then the black person before them no longer embodies that narrative and becomes Condi or Chris. It’s all about the projection and not about the person. And the projection comes from everything hateful and violent that built this country—the legacy of slavery, the fact that black people started out as property.

BLVR: Enough people will argue that it’s pragmatism or statistics, not racism, which makes them change behavior.

CR: As you know, the book doesn’t take place in urban America. It takes place in the world of middle-class America… on airplanes, with colleagues, at the shrink. We are not talking about some abandoned neighborhood in Detroit that has a statistic about police violence.

I made a conscious decision to bring our gaze back to places, which we are moving through constantly in our middle-class lives, places where we have expectations of equality. One doesn’t expect a colleague to feel as if it’s work to find, to locate your humanity.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3L_NnX8oj-g]

BLVR: You discuss Hennessy Youngman’s How To Be A Successful Black Artisttutorial. You mention how Youngman “wryly suggest[s that] black people’s anger is marketable. He advises black artists to cultivate ‘an angry nigger exterior’ by watching, among other things, the Rodney King video while engaging their practice.” Later in the video, Youngman asserts that “Above all, you got to keep them white fuckers away from the man behind the curtain. Don’t let them know that your dick be regular… or that you have a savings account, or that you recycle.” Youngman is warning black artists from revealing to their white audience how similar they are inside.

CR: Hennessey Youngman is intentionally provocative. But on the question of interiority and the black artist, I feel that it was important for me to talk about the interior space of the abstracted black body in Citizen, to talk about it separate from events and the scandal of racist assault. Once you leave the scene and you arrive home, what then happens to you? How do you negotiate everything that has been taken in? What does that sense of being overwhelmed by attempts of erasure feel like? In contrast with what Youngman says, I felt the book would have been incomplete without moving into those more interior and intimate spaces.

BLVR: Interestingly, most of the interior sections take the form of verse. As if linear prose (like linear thought) couldn’t contain the complexity of the character’s experience.

CR: Well, the more lyric sections carried the weight of history with them, but they allowed for a more complicated, indirect relationship with narrative. So there wasn’t that need to tell a story. The lyric created the lines to sit inside the feeling that the stories had blurred out. The prose sections and the essays have their own logic in terms of what they do with narrative. The poems, as tied to history and the politics as they still are, don’t necessarily have to work as narrative. They don’t have to work linearly. I think verse allowed for the accumulative buildup of feeling to happen through the use of poetic forms like repetition and anaphora.

BLVR: The last and, in many ways, most harrowing image in the book, is British Romantic William Turner’s Slave Ship. Slave Ship reminds me of Brueghel’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus. I would have probably missed the slave’s leg if not for the close-up you provide.

CR: How does that go… the Auden poem? About suffering they were never wrong…That’s the other aspect of Turner’s painting that was important to me. It works at the lightning speed of those micro-aggressions. If you look you don’t see the bodies being dumped in the ocean…until you look. Others can go through the day thinking, ‘Nothing has happened in this day at all.’ You can look at the image and not necessarily see what is going on. You can see it as a sunrise or a sunset, not as a mass murder, not as the approaching storm.

J.M.W. Turner, The Slave Ship (1840). Oil on canvas. 90.8 × 122.6 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Photograph of Claudia Rankine by John Lucas.