The following is an excerpt from a new Online Exclusive by Anne Valente on the commercially fraught, existentially intoxicating story of Sea Monkeys. Read the full piece on Believermag.com.

DISCUSSED: Speck, Enormous Numbers of Tiny Animals, Favorable Conditions, The Sanders Brine Shrimp Company, Green Hornet, A Distant Namesake, A Concealed Weapon, Fun and Fantasy, Peter Nero

Imagine yourself as a child. Imagine yourself lying awake at night, tucked into sheets. Imagine yourself as aware of your own smallness in the world—a speck, looking at the ceiling and its textured paint and seeing only the stars beyond it, then galaxies, then only galaxies beyond other galaxies.

Imagine infinity in your small brain, untainted by the weight of endings. Imagine your wide-awake terror as you contemplate its span.

Imagine the Midwest. A stretch of plains and trees, of ice storms and snow. A wave of hills that tumbles in a landlocked swell toward the ocean, miles upon miles of rolling cornfields that form the crest of what was once a sea. Imagine yourself a child born upon these plains, your eyes closed, in the lull of ocean waves.

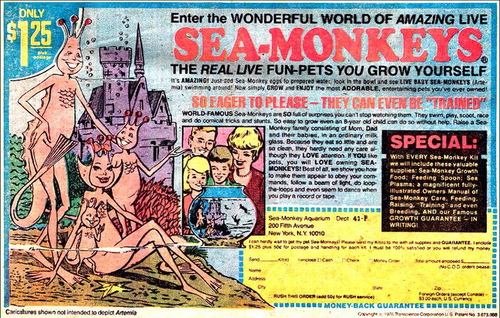

Imagine infinity encapsulated in the red plastic of an aquarium, shrink-wrapped, a gift resting in the palms of your hands. Imagine unveiling it, tearing open a packet, emptying it into the aquarium upon your nightstand, pouring water over the packet’s contents, and waiting patiently. Imagine three days later, as you lie awake in the night, how infinity collapses when you roll over in your sheets, when your face draws close to the aquarium, when you squint to see life, suddenly bloomed and billowing through the water: from here, upon the Midwestern plains, the expanse of the stars and the ocean contained at last.

In 1833, frontiersman Joseph Walker mapped Utah’s Great Salt Lake. Traveling west from the central plains with 110 men, under the guidance of Captain Benjamin-Louis-Eulalie de Bonneville, a US Army officer and the leader of a westward expedition that would map central routes of the Oregon Trail, Walker was assigned the task of splitting off to explore the lake and a potential passage to California. Though Walker mapped the terrain, the salt flats he encountered took the name of his guide, as did the ancient lake from which the Great Salt Lake was formed: Lake Bonneville.

Today’s Great Salt Lake is a remnant of this prehistoric body of water, which once covered most of western Utah and parts of Idaho and Nevada. Lake Bonneville was originally a freshwater lake, spanning nearly twenty thousand miles and emptying through tributaries into the Pacific Ocean. But following a decrease in rainfall over centuries, outflow through these rivers lessened, and eventually the water evaporated. Lake Bonneville dried and shrank, becoming the Great Salt Lake.

Today, the only outlet for water from the Great Salt Lake is evaporation, and the circumference of its shores fluctuates yearly, its area between approximately seventeen hundred and three thousand square miles, depending upon rainfall. The water is shallow, the salinity high, and, as Gladys Relyea reported in the 1937 issue of the American Naturalist, “oxygen content is very low; its nitrogen content is about half that of sea water; its organic matter is limited; and its carbon dioxide content is twice that of sea water.” It is an environment that cannot support most forms of life.

Still, as Joseph Walker mapped its contours and the remnants of its predecessor, he came upon “enormous numbers of tiny animals swimming about in the shallow water near the shore.”

The brine shrimp, also known as Artemia, is one of the few life forms that can survive in the inhospitable environment of the Great Salt Lake. It shares its habitat with algae and brine flies, and draws an astounding host of migratory birds to Utah to feed.

Brine shrimp are small, ranging in length from 0.3 to 0.5 inches. They are translucent and look like billowing feathers as their legs propel their small bodies through the water. And they are ancient: a State of Utah study found, based on geologic core samples, that “brine shrimp have been present in the Great Salt Lake area for at least 600,000 years.” Some researchers believe that brine shrimp are, in fact, descendants of a type of shrimp that once lived in Lake Bonneville. According to the Southern Regional Aquaculture Center established by Congress: “Based on physiological traits, scientists believe that brine shrimp were originally a freshwater species that adapted to saline water.”

Other experts believe that brine shrimp arrived at the Salt Lake as embryos, in hardened shells that could be easily transported upon the feet of migrating birds. This is possible because brine shrimp are born either as live young or as cysts, depending on environmental conditions (changes in rainfall, water temperature, and how much algae exist as a food source). When conditions are favorable, usually in the spring months, when the water is warm and phytoplankton are plentiful, female brine shrimp give birth to a combination of developing embryos and small babies called nauplii. Nauplii have indistinct bodies, short antennae, and a single eye. They float through the salinity of the Salt Lake, feeding upon algae and phytoplankton, and in time grow into fully developed brine shrimp. But if the water is cold, if there’s not much sunlight—if the algae can’t support new life—female brine shrimp lay cysts that encase a dormant embryo in a hard protective shell.

These cysts exist in cryptobiosis, a suspended state of life in which the Southern Regional Aquaculture Center claims the shrimp can withstand “complete drying, temperatures over one hundred degrees Celsius or near absolute zero, high energy radiation, and a variety of organic solvents.” The brine shrimp embryo can remain in this dormant state for years, until warm salt water and oxygen coax it from the chamber of its cyst, and the embryos unfurl into a brand-new world.

These more-visible cysts are likely what Joseph Walker encountered upon the shores of the Great Salt Lake in 1833. In the Utah fall, just before brine shrimp die off en masse in the winter months, wide swaths of cysts called “streaks” often appear in the lake water, coating the surface near the shore. Modern-day brine shrimp harvesters say these streaks resemble oil slicks spanning the surface of the water in layers. They must have seemed a form of magic to Walker’s untrained eye. A century later, in 1950, fishermen noticed migratory birds feasting on the shrimp. This led to a growing demand for aquaculture and a growing number of fish hobbyists, and the brine shrimp industry began to flourish. The Great Salt Lake’s first harvest took place in 1950 through the Sanders Brine Shrimp Company, the nation’s oldest brine shrimp harvest corporation. Though the Sanders Company originally harvested only live shrimp and nauplii, in 1952 it transitioned to collecting only cysts, when it realized the dormant shrimp could be sold to commercial hatcheries around the world as a lucrative food supply for fish.

In fact, brine shrimp cysts can lie dormant for up to twenty-five years—more than an entire childhood, the child’s resting hands waiting, mixing packets and water and raising a creature seemingly from the dead, to conjure magic with little more than bated breath.

Read the full piece on Believermag.com.