A Survey of Writers on Contemporary Writers

Listening to writers read and discuss their work at Newtonville Books, the bookstore my wife and I own outside Boston, I began to wonder which living, contemporary writers held the most influence over their work. This survey is not meant to be comprehensive, but is the result of my posing the question to as many writers as I could ask.

ANN PATCHETT

© Francesca Rheannon

MARY BETH KEANE: The first time I read Bel Canto was for pleasure. I picked it up at a bookstore and likedthe first page. I didn’t know a thing about opera— still don’t—but I quicklylearned that my ignorance didn’t matter. I read Bel Canto the second time to figure out how in the world Patchett pulls off such a perfect book given the limitations she set for herself. Virtually the entire story takes place in a single room. People cross thatroom, and cross again. They eat. They sleep. There’s very little flashback. Anyaction had to be plotted within those walls, with big moments—the momentsthat must move a novel—captured by small triumphs. And she pulls it off!Within that small space—the Vice President’s home—is contained passion,romance, hope, despair, everything a novel needs in order to be great. And this

novel is great. Whenever I’m frustrated with my own progress, and start feeling

that my characters should do more, should see more, should move more, I think

of Bel Canto and remember that

everything I need is contained within, not without.

JAYNE ANNE PHILLIPS

© Granta.com

NICHOLAS MONTEMARANO: I came to Black

Tickets when I was twenty-five and about to head to Prague to take a

workshop with Jayne Anne Phillips. By then she had published four books—two

novels and two short story collections—but I was unfamiliar with her work. Not

long after opening Black Tickets I

recognized its “dazzling virtuoso range” (Tillie Olsen), its “crooked beauty”

(Raymond Carver), and its “knockout prose” (Annie Dillard), a rare case when

hyperbolic blurbs are accurate. It remains a seminal influence on me as a

fiction writer for many reasons, but here are two. First, Black Tickets is more than a collection of short stories; it is, in

its structure and thematic unity, very much a book. It doesn’t feel patched together but conceived. The

collection, with its rhythm of longer stories and micro fictions, hearkens

Hemingway’s In Our Time. After

reading Black Tickets, I never again

wrote short stories outside the larger vision of a book. Second, and perhaps

most important, is the voice—rather the voices—in

her stories. She shows range—there are stories in Black Tickets with subdued voices and more traditional approaches

to storytelling—but the collection creates its true power with its voices.

Almost every sentence from the dark, beautiful title story is quotable, but its

opening will do: “Jamaica Delila, how I want you; your smell a clean yeast, a

high white yogurt of the soul.” Phillips, who wrote poetry early in her career,

is a poet writing prose. Black Tickets

taught me, and continues to remind me, that the music of prose, its sound and

rhythm, matters greatly to me. I learned other things from Jayne Anne herself.

I don’t remember the Prague workshop with her except the feeling of being taken

seriously as a writer, and that mattered to me then. I saw her again years

later when we were both fellows at The MacDowell Colony. I remember visiting

her studio there and seeing pages of her novel-in-progress taped to the walls.

Some people call her a slow writer, but I think of her as careful and

methodical, in no rush to publish anything that isn’t her best work. I’m

grateful for her example of patience. One of my proudest moments as a writer

remains Jayne Anne’s blurb of my first novel. She called me “an American

stylist capable of redeeming our darkest dreams,” something I could say about her. If there’s any truth to that, I owe

much of it to Jayne Anne’s influence, especially her first book. These are just

a few reasons why last year I spent $60 for a first-edition hardcover of Black Tickets and why it sits on my

desk, along with other favorites, as inspiration.

MARY OTIS: I first read Jayne Anne Phillips in the Santa Monica

library a week after I’d moved to Los Angeles from the East Coast. It was a hot winter day, and a strange sun

the color of a children’s aspirin lurked outside the library window where I sat

with a copy of Black Tickets in my

hands. It was afternoon, and then it was

evening. I was transfixed, captured in a

way that only the best writing makes possible.

I felt like the character, Lark, in the Phillip’s novel, Lark and Termite, who while in a typing

class, imagines “flying above the town and the trees and the river,” and as

long as she types, won’t crash. But in

my case, as long as I kept reading that collection and didn’t stop, I could

stay inside the world of her stories that taught me everything I needed to know

about what it means to take a risk in writing.

Not a risk to simply shock, but a risk to go all in, to tell the deep

human truth. Her writing illuminates all

that is strange and sad, and beautiful beyond comprehension, too—the edge of

wonder.

Phillips

followed Black Tickets with Machine Dreams, Fast Lanes, Shelter, Motherkind, Lark and Termite, and most recently, Quiet Dell. In her stories

and novels she is compelled by the dislocations of thought, the mysterious

territory of living, and how the past imprints itself upon us. She writes with a poet’s sensibility, and her

lush prose breathes and sweeps, is masterful in its precision. She has said, “We look for mirrors of our

humanity everywhere,” and this idea recurs in her explorations of family, loss,

and the difficulty of communication.

Phillips is a master of the emotional interstice, one who mines the

ordinary moment between things to reveal everything that can’t be said and the

only thing that matters.

I wasn’t a writer yet

when I first read Jayne Anne Phillips that day in the library, but she gave me

a memorable jolt—one that made me want to become a writer, to stay awake, tell

the truth, and name the unnamable.

RICHARD POWERS

© Jimmy Kets

WESTON CUTTER: Here’s the best way I know to think about the work

of Richard Powers—a body of work which stretches over now nearly thirty years and

eleven books: while his books are classified as novels they are, all of them, longings,

and the longing each novel enacts has to do with how we connect with and

apprehend anything like meaning in the world. Such a broad claim is of course a

gross simplification: what novel doesn’t in some way solve for that

formulation? When we for instance read Franzen, we understand through the story

and its characters’s travails how we might deduce something about how we might

better live in or value or appreciate the world—we understand, say, that total

selfish freedom does not set the soul quite free. The trick with Powers,

however, is his directness: the reader’s not led to deduce larger abstractions

from the small-scale lives on the page but is instead offered raw complexities

and is trusted to navigate them. That gasp folks often let loose when they talk

about Powers has something to do with audacity: that he’d be willing or foolish

or whatever enough to be so direct.

Here’s another way to say it: Powers is writing, again

and again, love stories that (like most) begin between minds. When his characters

fall for and toward and onto each other, the falling’s most often the result of

the heightened living that attends sharing an enrapturing trance regarding some

abstraction. For instance: two people become fascinated with an older man who’s

doing third-shift computer coding, and they begin to try to research his life,

to find out how he ended up where he’s ended up, and in the process these

characters fall for each other. Could anything be less surprising?

To address some basics: James Wood in his otherwise

forgettable 2010 critical take-down of the work (“Brain Drain”) does

a passable job articulating something of the shape of Power’s fiction. “In his novels, Powers

generally likes to keep two plots going. One story line poses, and tries to

solve, a relatively abstract puzzle: Does the human mind function like a

computer? Does genetics offer the best explanation of “the riddle of life”?

What is the nature of consciousness? The second story line is almost always

boy-meets-girl, in which protagonists connected to the first plot meet and fall

in love or lust.” Wood is here (as in 98% of the rest of his take-down)

implying such a binary is bad, or lacking, yet what Powers is examining, again

and again through his braided plots, is overwhelming: by what structures will

we make meaning of existence?

Take

a moment with that question. By the time most of us sign our names to mortgages

or student loans, we believe we’ve not only got some sense of what’s capital-I

Important, but also some sense of how to move through the world to secure the

treasure we believe is most valuable—love, loyalty, lucre, whatever. What

Powers does, again and again, is present novels in which characters have to

reevaluate all of that: what if you’re a reference librarian and discover that the

most vivid, compelling living is being done outside the bounds of what books

and magazines might record? What if you’re a writer and discover that the

student who’s making your classes come to a new sort of life may be genetically

coded for happiness? In other words: what do you do when the systems you’ve

believed in crumble, are proved false? What do you believe in then?

The

simplistic knock on Richard Powers’s novels is that the ideas are more animated

and compelling than the characters—that, to quote Wood, his fiction

“resembles a dying satyr—above the waist is a mind full of serious

thought, philosophical reflection, deep exploration of music and science;

below, a pair of spindly legs strain to support the great weight of the

ambitious brain.” But Wood, again, is painting criticism onto amazement:

what’s wrong with Powers’s novels featuring cognition as the central verb that

leads to love? His characters apprehend the world through experiencing it and

then thinking and reflecting about it. Does everyone live thus? Of course

not—but no fewer people live like this than those who live precisely like the

folks one’d find in any of Powers’s contemporary’s novels. No: his love stories

don’t feature characters bumping along, attempting to figure out if they’re

compatible due to how they take their coffee, or what TV they watch. There is,

in all of his work, some deeper tidal movement in all the characters, a sense

that some deeper and more deeply animating aspect of being alive is available

to us only if we keep doggedly searching. Here’s how Stuart Ressler puts it in The Gold Bug Variations: “all

longing converges on this mystery: revelation, unraveling secret spaces, the

suggestion that the world’s valence lies just behind a scrambled facade, where

only the limits of ingenuity stand between him and sunken gardens.”

This

is the object of the longing throughout all Powers’s books: some way to solve

for the mystery of being alive, for the glory and horror and awe of existence.

“Pleasure in existence is a moral imperative” he wrote in a slim

advice-offering book titled “Take It From Me,” and decode the phrase,

consider the fact that he’s implicitly arguing pleasure’s more than merely an

aesthetic or sensual phenomenon. There is, of course, no single answer, no one

way to solve for life’s mysteries: even any grand unified theory in physics

couldn’t explain the murkier interstices—love, pain, the rush and humbling

attendant in any search for answers. Powers, again and again, proposes binaries

only to smash them, to (of course) say both,

to let his characters hunt and try through their experiments of living only to,

by each book’s end, find themselves saying again and again yes and to head and heart, to fate and free will, to the complex,

answerless notion that life is most life when it’s an attempt to reconcile the

twin pulls within us.

ANNIE PROULX

© Eamonn McCabe

ANNA SOLOMON: “Hive-spangled,

gut roaring with gas and cramp, he survived childhood….” So begins The Shipping News. My battered copy

still flops open to the first pages, which I read again and again my first time

through, mouth open. You can do that?

I thought. Sentences were missing their subjects or otherwise incomplete; nouns

and verbs, even adjectives, seemed interchangeable. I could find no center, and

yet it held. And held, and held.

That

first reaction was as a student of poetry, as I was just beginning to write

fiction. Looking back, it was a pivotal moment in my gradual humping (Proulx’s

verb) toward prose. I loved that one could play so freely with language, write

something that begged to be spoken aloud, and

tell such an intricate, complex and lengthy story. I was inspired and

emboldened.

As I

wrote and studied short stories, I continued reading Proulx for her language,

but also for her tricks of structure, point-of-view and character development.

She would dance through a century in a paragraph, leap bravely from one

character’s perspective to another, make people and places vivid with a single

word. Her stories were driven by often outrageous plots, yet these plots were

so intimately bound up with her characters that it all felt inevitable,

necessary, true. There was a kind of hyper-reality to her stories (the bizarre

names, the even more bizarre things that happened) and yet a simplicity, too,

borne out of specificity: I could see, hear, often smell the people she wrote

about. (Most didn’t smell good.) Their bodies, their belongings, their trailers

and trucks, the sky and ground around them, were so concisely yet richly told—each chosen word serving more than one purpose—that I would have gone with

them anywhere. I never thought, well, that would never happen. Because it did.

These

days, as I work on my second novel, I return to Proulx for language and craft,

and for something more intangible: her constant play between light and dark. In

moments, her descriptions can come off as irreverent, even flip, yet they

commingle with the opposite: such deep respect for her characters, such care in

describing their inner and outer selves, that I can’t help but love them, too.

Like them, maybe not, but love them, yes. Light, dark, comedy, tragedy,

surface, depth—Proulx keeps moving, dismantling our assumptions and

surprising our aesthetics. Her work exudes the kind of freedom that can only be

achieved through great control. So I read it and I keep on with my own work,

letting go, pulling back, trying (but not too hard) to find the right balance.

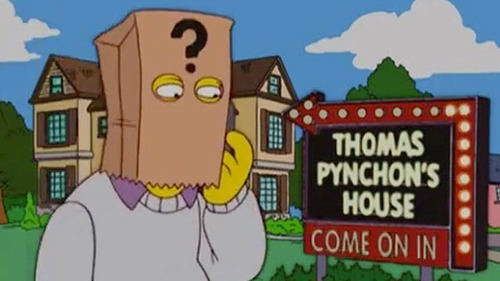

THOMAS PYNCHON

RYAN BOUDINOT: Thomas Pynchon had a pretty profound effect on me. I

started reading his books as an undergrad, and for the first time felt two

conflicting things I’d never felt when reading a book. One, I was utterly

entranced. And two, I didn’t know what the fuck I was reading. His work

perplexed me, but the rhythm of his sentences and the combination of vernacular

and sophisticated technical language was like candy to me. It was the high/low

language combination that felt totally right to me. And I had this weird

feeling that his books were reading me, not the other way around. Like there

was some sort of subconscious communication happening that my critical mind

wasn’t privy to.

—

Mary Beth Keane is the

author of the novels Fever, and The Walking People

Nicholas Montemarano is

the author of the novels The Book Of Why,

and A Fine Place, as well as the

short story collection If the Sky Falls

Mary Otis is the author

of the short story collection Yes, Yes,

Cherries

Weston Cutter is the

author of the short story collection You’d

Be a Stranger, Too

Anna Solomon is the

author of the novel The Little Bride

Ryan Boudinot is the

author of Blueprints of the Afterlife,

Misconception, and The Littlest Hitler: Stories

—

Lettering by Caleb Misclevitz

—