Christopher Noxon is a Los Angeles-based author whose debut novel, Plus One, traverses the life of a husband and father, Alex, who just happens to be married to a screenwriter newly successful in creating and running a zeitgeisty premium-cable series. It’s important to note that Noxon is married to Jenji Kohan, creator of Orange is the New Black and Weeds. For Noxon “plus ones” are the partners of the talent invited to events like awards shows, and along with painting the portrait of a contemporary Hollywood marriage, the book offers a comic glimpse into an admittedly niche subculture: those folks partnered with celebrity types often found shopping for trendy clothes and buying pounds of wild animal flesh in high-end Los Angeles butcher shops—that is, when they’re not dutifully serving as “domestic first responders” and “family CFOs.”

Last week, I had an early breakfast with Noxon, during which he proved inordinately good-humored and at peace for a person who wears many hats and must regularly drive across Los Angeles during rush hour to drop off and pick up his kids. The following text comes from a conversation we had the next day.

THE BELIEVER: Let’s start with my best attempt at a Charlie Rose/US Weekly-ish question: What was it like working with… yourself (on this book)?

CHRISTOPHER NOXON: When I tell people I wrote a book about a guy married to a successful TV writer, the joke comes easily: “How’d you possibly come up with that?” My lead character Alex is an Angeleno, the son of lesbians and the husband of successful TV writer. Let’s just say if we met at a party Alex and I would have a lot to talk about.

But I swear Plus One isn’t a straight roman-a-clef. The truth is I took my life and exaggerated and condensed and expanded and reimagined it. True-life facts and feelings got mixed up with bits borrowed from friends, events that never happened, and material I invented whole cloth. Alex isn’t me any more than Figgy, Alex’s wife, is my real-life wife, Jenji.

Alex is my attempt to create an agreeable, conflicted “soft man” raised by well-intentioned feminists to “follow your bliss”; Figgy is an ambitious, intense working mother raised to believe she could “have it all.” In those ways, Alex and I are much more alike than Figgy is like Jenji, whose parents weren’t exactly encouraging of her career (her mom famously told her after college that she should go sit on a bench at CalTech and meet a nice man to support her). I could list the many big and small ways the book differs from real life but I worry about lingering too long on the question of what’s “true.” Doing so shoots the book full of holes and turns the narrative into a guessing game. Let’s just say I hope it all feels true.

BLVR: Were you worried as you wrote this book about “relatability,” the word that Rebecca Mead wisely took to task in a piece last year for The New Yorker that discussed Boyhood, and its attempt to be the American everyperson’s movie? If you weren’t worried about relatability, do you have feelings on the issue? Certainly it’s more of a concern when you’re writing a feature script for a big studio.

CN: I’d like to take the high road and say I reject the whole notion and I just strive to make my characters truthful and as ugly as this great messy thing we call humanity… but I get it.

My main character is a well-off white guy married to a successful TV writer—right off the bat, a lot of readers are going to hate that guy. Or at least have very little patience for his troubles. So I had to think long and hard about how to get past that.

First thing I hope helps readers feel a connection is voice. I’ve read tons of fiction about horrible vain shallow people who I still love to spend time with on the page—and I think that’s mainly because of the clarity or surprise or distinctiveness of their voice. Whatever central thematic idea I’m circling around is always subservient to the pleasure imperative. All I mean is that for me, reading has to be pleasurable. Otherwise, I’m ditching the book and turning on Netflix. There’s way too much good TV right now to write dull.

BLVR: In your book, the main character Alex learns about Plus One fashion from the husband of a famous actress. Back then it was French skinny jeans. What are the hottest Plus Ones wearing this season?

CN: The French skinny jeans are definitely passé in the 1-5 [2015]. Which is a huge relief, because I’m pretty sure I did permanent damage to my internal organs with a pair of APCs.

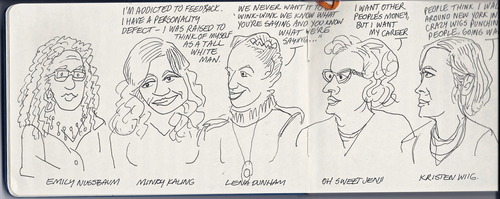

BLVR: You drew the illustrations in your book, and you carry a journal with your sketches. Have you found that many Plus Ones are as equally adept in the arts?

CN: I’m a habitual doodler and journal-keeper, but I’ve yet to find another Plus One who shares this particular arty practice. Most Plus Ones have a sideline—we’re all hyphenates of some sort. Producer-slash-photographer-slash-pickler. Anything but house-husband. I halfway jokingly refer to myself as a “domestic first responder.”

BLVR: Before you wrote this book had you surveyed the Plus One literature? Is there Plus One literature? I’d love to know how the role has evolved over time to be fair to all of the spouses—women and men—of famous and/or successful entertainment people who came before you.

CN: The Plus One lit micro-genre! I did read a few books that cover some of the same thematic territory—Ann Leary, wife of the actor Dennis Leary, wrote a terrific novel called Outtakes from a Marriage that deals with many of the same thorny issues. Also Meg Wolitzer’s The Wife, one of my favorite books of all time, about the partner of a Nobel-winning author.

BLVR: Do you enjoy the anonymity of being a Plus One?

CN: There are huge pluses to the Plus One role. Anonymity being a big one. Jenji gets really uncomfortable when she has to go out and be on (and gussied-up and made-up etc.). Meanwhile I can just hang back and soak up the weird spectacle. Which I enjoy.

BLVR: You get into LA real estate in the book, and clearly we’re all living in an age of terrible income inequality and exorbitant housing prices. But can we just dispel one myth? When you live in a pricey city like LA, and you have kids who need schooling, among others things, being a TV writer—even an employed, creatively successful one—is not a guaranteed, risk-free road to hardcore wealth, right? Yes, one is lucky and likely has much more financial prowess than most Americans as the kind of Plus One (and Family CFO) you write about, but isn’t it wrong that most TV writers in our streaming age live like the hedge-funders who blow up yachts, jump on Frank Lloyd Wright houses, and are never concerned about finances? Some TV writers live opulently in LA, even after paying nearly half to the agent, the manager, the lawyer, the accountant, and the government, among others. But in this city, where a lot of the work and the studios are, average-sized dwellings in unpopular neighborhoods that seem “normal” to the rest of America can cost a lot more than what they might fetch in other parts of the country.

CN: There’s a huge difference between hedge fund/banker/top tier money and the kind of deals that TV writers make. But this is a touchy subject, obviously, because it’s still a lot by any reasonable measure. Problem is, as you say, we’re not living in a reasonable-measure world. Houses, schools, lawyers, agents, etc.—it’s insane how much cash it takes to keep a family afloat here.

BLVR: I’m also interested in the financial risk involved in being a TV writer. I mean, you can sell a show for the guild’s standard rate, and then do nothing ever again. And it’s even more like playing the lottery now, especially with contests like Amazon’s Pilot Season.

CN: True—job security is sorely lacking in the TV biz. Hasn’t it always been so? Also true for actors, directors—really all the creative, above-the-line gigs. At least now with the Amazons and Hulus and web-whatever-the-hells, you have a shitton of of new outlets. These new outlets don’t pay big network money—often they pay next-to-nothing—but at least theoretically you can now make a living writing, and you might even make a living writing something that isn’t horribly bland or generic or “likable.” There’s a new middle class of TV writing that just didn’t exist five or ten years ago.

BLVR: I’m also curious about the payoff in terms of stress. We all have it. But even a well-known showrunner in TV with a big salary is very often not living a relaxed life, and when executives call and want 1200 pages of coherent material written in mere months, it can’t be easy. Stress is not free, and it can cost one bigtime no matter how much they may earn in dollars. Many a fine novelist couldn’t even handle the stress of writing a 250-pager in a year’s time. Relatedly, I like to say that calm is also currency, and you can be poor in calmness.

CN: Yeah, there’s a line in the book that describes that exactly: “TV is a pie eating contest and the prize is more pie.” The better you get at it the more punishing it gets. Which is why there are so few people at the top tier of the business who can reliably produce good TV without cracking up—I have no idea how someone like Shonda Rhimes does what she does. My guess is that writers at that level have an entirely different process—they are so locked into their characters and stories that they crank it out without the insanity or second-guessing that mere mortals endure.

BLVR: It seems like the best thing about both being a plus one and reading about your Plus One character Alex, is the Positive Enabling. You’re not enabling your spouse to continue some unhealthy addiction but you are enabling them to enjoy life outside of work. For that reason it seems like the Plus One’s role is terribly important in the relationship. And in some ways isn’t being the Plus One, at least in your book, a chance to sort of earn respect as a person who knows (or learns) how to do important life things, like buy real estate and invest?

CN: Positive enabling—I like that. You’re right inasmuch as I can make our lives better by handling stuff so she can concentrate on work. Downside is she can feel isolated and disconnected from the kids and family, and then there’s the fact that she’s a producer and producers produce. Meaning she can’t help herself—she sometimes has a hard time leaving the hierarchies at work. At home we’re partners, hopefully.

BLVR: What’s the loneliness factor when you’re a Plus One? What have so many of these Plus Ones over the years been dealing with in terms of social isolation? That’s serious shit, and for the record, relatable (or perhaps not, because maybe people in less-creative fields have more social opportunities). As a writer, I often have to be very creative about finding things to do with people during the workdays, and we all know that being lonely is bad for everything—and that spread-out LA doesn’t make it easier.

CN: Yeah, isolation of the caretaker role is a real danger. That way lies sadness. I’m honestly not jealous of my wife at all—when she succeeds I’m psyched. It never occurred to me to feel threatened by her success. But the one thing I am jealous of is the number of awesome, interesting, artistic, productive, and cool people she gets to hang out with all day. Her writer’s room and staff is just lousy with brilliant people. Meanwhile there are days that go by when the only people I talk to are the nanny, a mom at carpool, and my butcher.

BLVR: You wrote a pilot based on the book for ABC. Clearly, this sort of thing is not new for you, but do you think that novelists are going to need screenwriting talent (not just skill) as the culture progresses?

CN: I’m surrounded by TV writers (wife, sister, brother-in-law, friends, dad, etc. etc.) but I had always resisted trying it myself, in part out of snobbishness (non-fiction felt more noble). Mainly I didn’t like the idea of competing with the sadsacks with laptops I see at every library and cafe in my neighborhood. I finally crossed over when ABC optioned the book and my agent convinced them to let me write the pilot. I figured, even if they don’t make it (which they didn’t), I’ll make more from these forty pages of script than I probably will from the three-hundred pages of the novel. So even if the novel sputters like the vast majority of books published these days, at least it won’t be a loss-leader. I will have paid my way with this thing. All of which gives you a pretty good picture of my Plus One mentality.

BLVR: “One never acknowledges or predicts good fortune, lest one incur fate’s capricious wrath.” That’s from your book—an Oscar Wilde-like statement that you use to describe the attitude of Alex’s wife Figgy. Can you elaborate?

CN: Ah, yes—the unforgiving power of the evil eye. I feel like it’s a Jewish-Ashkenazi thing, but yeah—a lot of people I know (including my wife) operate under the assumption that bad things happen when you say out loud when things are good or you’re happy. In the book, Figgy makes a deal with herself—she can live with the rewards of her work as long as she never acknowledges them out loud. My own wife is a little less superstitious than Figgy, but she’s also given to making that pew-pew sound when anyone dares speak of how awesome things may have turned out.

BLVR: Speaking of which, you scared the shit out of me writing about a rat in the book (I won’t spoil it for readers by saying more). Anyway, writers have always frightened me about rats more than rats themselves. This begins for me with that great piece about the rats of the NY waterfront by Joseph Mitchell. I didn’t know you were going to be on my rat list (feel honored now?). But that says a lot to me, especially as a newly empowered catcher of lizards in my canyon home. Only awesome writers get on my rat list. Can we talk here about the funny rush city people writers get from being able to capture or exterminate vermin? I would also like to invite you to co-lead a support group with me for the urbane who’ve thought of using Taschen art books as tools or weapons.

CN: Yeah, as feeble-bodied lumbery twitchy writer types, we have to pick our foes wisely. Nothing too threatening or forceful. Lizards are good. Bears bad. Vermin are horrible, but they’re really not all that hard to control. I guess what I’m saying is any schlub can set a trap. And then feel ridiculously victorious when it catches something.

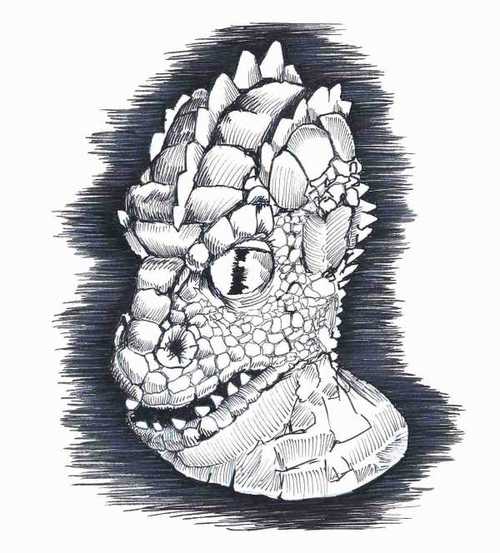

Illustrations by Christopher Noxon from Plus One, and sketches of Lena Dunham, Mindy Kaling, Kristin Wiig, and Emily Nussbaum from Noxon’s journal at Sundance.