A Conversation with Adam Green

Musician and artist Adam Green was in born in 1981 and grew up in New York. He became known as one half of the anti-folk band The Moldy Peaches, which he formed with Kimya Dawson. The Moldy Peaches went on hiatus in 2004, but continued to write music, contributing several songs to the soundtrack of the film Juno, including the evocative duet “Anyone Else But You.”

Since then, Green has produced seven solo albums, Garfield (2002), Friends of Mine (2003), Gemstones (2005), Jacket Full of Danger ( 2006), Sixes & Sevens (2008), Minor Love (2010), and MusiK for a Play (2010). His most recent record is album of duets with Little Joy’s Binki Shapiro, produced in 2013. Although Green identifies as a folk singer, his songs defy generic classification.

Green has also staged a number of solo and collaborative art shows in New York and around the world, including Teen Tech (2010), Cartoon & Complaint (2012), Leisure Inferno (2012), and Houseface (2012), a collection of works inspired by De Stijl and the architecture of Friedensreich Hundertwasser and Antoni Gaudí. Like his music, Green’s painting and sculpture defies categorization, but often references aspects of ‘80s and ’90s popular culture in recontextualized formats. His most recent exhibit was Hot Chicks (2014) at The Hole Gallery in New York, a show which included friends and artists such as Devendra Banhart, Taylor McKimens, and Matt Leines.

In 2011, Green released his first film, The Wrong Ferarri. Shot entirely on an iPhone, it was written, directed, and performed by Green and featured cameos from Banhart, Pete Doherty, Sky Ferreira, and Macaulay Culkin, among others. Green is currently working on his next film project, a version of Aladdin.

—JT Thomas

I. THE VITALITY OF THE HUMAN HAND

JT THOMAS: I know that you’ve been making music since you were fairly young. Why did you start making visual art six or seven years ago? Was sculpture and painting something you had been involved with for a long time, but just not professionally? Or were you just drawn to it suddenly?

ADAM GREEN: As a kid I wanted to be a cartoonist. I think I perceived Garfield as a symbol of decadence and he became my entry point into living a life of excess. I spent my high-school years getting stoned and playing in a psychedelic noise band called NEEP. Some of those early musical experiences led me to try automatic drawing—I was attempting to make a visual representation of biomorphic noise, and so I developed my jagged line-style and my handwriting just the same, I even fuck like that! I studied art history for a long time but mostly kept it private because I didn’t have anybody to talk about it with.

JT: What are your influences in terms of your visual art? Not necessarily art world influences, but perhaps more broadly in terms of the culture. I see a lot of cartoon and video game references that are very specific to boy culture from my generation in the ’80s: Garfield, Nintendo Power Magazine (which they still make and I think makes a cameo in the opening scenes of your film, The Wrong Ferarri), Mario, Tony the Tiger, Masters of the Universe, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, etc. There seems to be an element of exposing the dark underbelly of this childhood iconography. I also see a broader pop-cultural brush in terms of visual references. I’m thinking of the “Jean Benet Basquiat” painting, a collaboration you did with Macaulay Culkin and Toby Goodshank. Or the Garfield/Piet Mondrian mashups from the HOUSEFACE exhibit, which are also particular favorites of mine. How did those come about?

AG: I feel that we are living inside a video game. And it’s almost neoclassical, this whole virtual-reality “second life” idea. There’s something monolithic about Microsoft Windows and iPods. I basically think of myself as a romantic symbolist living in the ironic epoch, and it sometimes drives me to express myself like a preschool Tintoretto. The icon whether it’s on the side of the Grecian urn or on the computer screen becomes the side-scrolling instrument and in this case Mario is the Jesus of Nintendo.

JT: What types of art do you find yourself looking at these days? I’m always reminded of Paul McCarthy when I look at your sculptures and paintings from your show Cartoon and Complaint, for example.

AG: A few years ago I got really drawn into the TV show Xavier Renegade Angel. It’s very underrated and also kinda reminiscent of Paul McCarthy’s stuff. I really love Matt Leines’ artwork and my wife and I just bought a painting from him. I’ve been checking out Andre Butzer, Ryan Trecartin, Eddie Martinez, Max Brand, and Taylor McKimmens. I find myself relating to Paul Thek in his desire to create pixelated, or at least cubic, flesh.

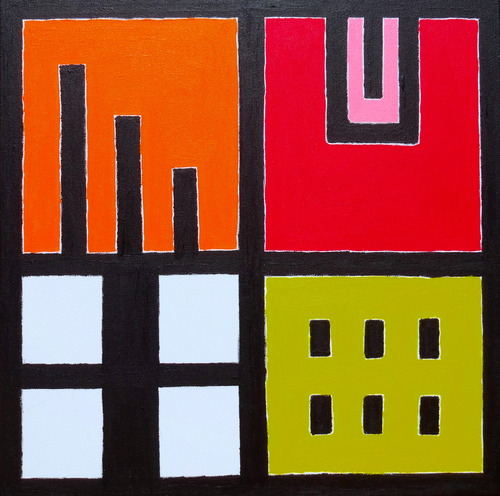

Cat Tongue Zoom (acrylic on canvas). Adam Green.

JT: My first experience with Xavier Renegade Angel was the episode where he forces one of the bigoted, homophobic townie characters to drink a gallon of AIDS. I’m not sure what that means, but it left an indelible impression on me. A lot of the artists you mentioned really remind me of either Basquiat or Philip Guston, in that they all kind of mix expressionism or neo-expressionism with cartoon-like iconography. Taylor McKimmens and Matt Leines’ work in particular has a particular illustrative quality. I love Leines’ tigers. What kind of art do you collect, other than his?

AG: I’m attracted to a specific line-quality, one that feels to me like it draws from human experience. I like it when the artist presses hard and puts their personal history and feeling into the line. It’s a reminder of the vitality of the human hand. The cartoon stuff is great because it has to do with our own sentimentality, but I think that Picasso was a cartoonist as well, and great artists largely work in caricature. My art collection is largely limited to people who I come into contact with in NYC; I recently acquired some pieces by Austin English, Alison Silva, and Devendra Banhart.

JT: Can you explain what your initial interest in making the “Zooms” paintings of hotels, power plants, main frame computers was? What are the “Zooms”?

AG: The Zoom paintings are derived from Big Bird, Garfield, and Elmo. In each I tried to distill their facial features down to a cubic-essence. The zooms represent these distillations in their most reduced form. It’s basically like making Garfield-crack. My favorite part about the reductions is that they can be used to design a sentimental animist architecture system which I call HOUSEFACE. Some people say the Zooms look like Mondrian and I welcome that comparison though I think they have more in common with a Monopoly board.

JT: I don’t know if I would be able to define the term “Garfield-crack” per se, but as a connoisseur of the Jim Davis oeuvre over the years, I know exactly what you are saying. I assume you’ve seen the genius that is the Garfield Minus Garfield website?

AG: Yeah, my friend got me the book recently, it’s incredible! I wonder what a kid would think if they picked it up and read it without an explanation.

JT: I actually bought the Garfield Minus Garfield book for myself, but it quickly ended up mixed in my kids’ ‘normal’ Garfield books. Maybe this is damnation by faint praise, but to Jim Davis’ credit, Jon’s pathos is just as hilarious to them without Garfield in the cartoon as it is with Garfield in the cartoon. They don’t really discern between the two.

Driver (oil stick on canvas). Adam Green.

II. “LOVE IS THE LAW, LOVE UNDER WILL.”

JT: Do you have a different audience in mind when you make visual art versus when you write music? I’ve read an equal number artists or writers that go out of their way to say alternately, “I only really make art for myself,” versus those who say things like, “If it isn’t accessible to my audience, I’m wasting people’s time.”

AG: I go back and forth. I certainly like to think that I’m at least relating to people with a feeling. Like with The Wrong Ferarri movie, some of my close friends knew immediately what it was about—it’s essentially an unrequited love story. But for everyone else I think it needs footnotes. It would be nice to have an enhanced body of work that includes footnotes, perhaps incorporated with a futurist technology like Google Glass. I think I‘d like that because my idea of fun is making a museum.

JT: What would the Adam Green museum look like?

AG: I think there would be multiple branches. The main branch would be with personal historical artifacts located in the Peloponnese in Greece. And all the other satellite branches would be video game portals setup in upstate New York towns like Syracuse, Troy, and Ithaca with all my personal history distorted and transposed.

JT: How does making sculpture and paintings compare to writing a song or making an album in terms of personal satisfaction? Do you get different things out of these mediums, or does it sort of stem from the same place?

AG: I’m always trying for a fluidity between music, visual art, and film. I think I got my first taste of that back when I directed some of my early music videos. Sometimes painting for me feels like making music without a metronome. At my best I feel like I’m tracing what’s inside my brain. At my worst I feel like everything is the same as everything else. I think Aleister Crowley was right when he wrote “Love is the Law, Love Under Will”. I believe that he was talking about the creative process more than anything.

III. KEEPING OUT OF TROUBLE

JT: I read somewhere online that your great grandmother was Felice Bauer, Kafka’s sometime muse and fiancée (twice!). Is there like Franz/Felice family lore? Did you read or maybe just avoid his writing because of this? I have an entire book of his letters to Felice, to whom he wrote nearly every day for years and years. It’s kind of interesting, because while a lot of what he says is very beautiful and love letter-y, it’s also just full of kind of tedious stuff like “Well, I went to the store today and bought…”

AG: There is some Felice-lore I’ve been told. Apparently when my family found out that Kafka had made advances on another woman, they summoned him to a hotel room where they admonished him. This experience of being probed by my great-great grandfather supposedly inspired The Trial. And in keeping with this, the character Fraulein Burstner (FB) is Felice Bauer.

JT: Were you brought up in a house that emphasized visual art or music? My parents sort of had aspirations to making art, but got completely side tracked in the course of raising a family, and so they never really followed up on it.

AG: My father is a neurologist, but as a kid he designed some greeting cards for Hallmark. At that time he won aNew Yorker drawing contest judged by Peter Arno and so he raised me to think that the New Yorker cartoon style was the paramount illustration style. My brother plays the oboe and the clarinet. He’s played on a couple of my albums. Actually, my family wasn’t particularly supportive about me doing music or artwork, and so I sort of had to “run away” from them for a while.

JT: What do they think now that you’ve been doing this for over a decade, and have been pretty successful making albums and producing other art?

AG: It’s very different now it’s true. I feel that my family accepts me as I am, more or less. I’m keeping out of trouble.

III. INVENTING CULTURE

JT: I notice that a lot of your work is highly collaborative, whether it’s recording with people like Kimya Dawson or Binki Shapiro, or painting or making films with people like your 3MB collaborators Macaulay Culkin and Toby Goodshank. How do you decide on the material you want to produce on your own versus material you want to collaborate on with someone else? For instance, I can’t imagine that collaboration would have really helpedMinor Love, which seems like such a personal record. But your most recent album is record of duets with Binki Shapiro, many of which also seem pretty personal. Is there type of work that you save for yourself, or is collaboration always on the table?

AG: All the collaborations I do are sort of psychological mindfucks where all personal boundaries get completely blurred. I space them out a lot because I often need years to recover from them.

Oranges (oil stick, crayon, acrylic, and graphite on canvas).

JT: Why do you need years to recover from them? Like physically? Creatively?

AG: Those projects often take years to execute, and I get a bit of cabin fever. Then I’ll come back to a place where I enjoy having a final say over the creative decisions, and I go off and do my own thing again. However I definitely learn a lot each time I do a collaboration.

JT: I saw your collaborative exhibit in New York at The Hole, Hot Chicks. Can you talk a little bit about how that came about, and how you got so many artist to be part of it? I noticed Tayor McKimmens was part of the show, and Devendra Banhart, who also started as a visual artist before he was known for making music. Do you find yourself with a lot of finished work or songs that you need to find a way to present, or do you come up with a general idea for a project or an album, so that it sort of forces you or gives you a concrete reason to come up with new work?

AG: The idea for Hot Chicks started on tour; I was jokingly trying to draw something that my guitarist could masturbate to. From there it developed into this idea of erotic information being transferred electronically, and in that glitchy process getting circuit-bent into grotesque 8-bit pixelated blocks. I was getting really into that James Ensor-ish pink-rubbery “white guy white” flesh color and I started to use it to create flesh-blocks of genitals and “tit-dicks.” I started to wonder what kinds of “Hot Chicks” my friends would draw if given the assignment, so I curated a show around that concept and it turns out that most of them are pretty grotesque as well!

In answer to the other part of your question, I do have an abundance of work I’d like to find a way to present. A lot of time that stuff just goes into a box, but since I’ve been doing more multi-media projects like movies the last few years, I’ve been finding a way to incorporate a lot more disparate elements into the same project. For example, a sketch or drawing style I explored for a few months becomes the basis for the way I design a room or an object in my movie. It’s amazing how much stuff I’ll cram in there!

JT: I’ve noticed you’ve now made your second record with Noah Georgeson. Can you tell me a little bit about your collaboration with him? In terms of your song writing, the last two albums seem a lot more serious in tone than your first records. Is the Leonard Cohen-ness (for a lack of a better adjective) of the songs something he wanted to emphasize in the recording process?

AG: I’ve actually known Noah since I was twenty years old and even back then everybody said I should record with him. It took me almost ten years to give him a call. I’ve always felt that my music existed in a place that was medium-serious and I guess it’s done me no favors with the critics. Noah understands that about me, that we can record a really sad record, but still just hang out and talk a bunch of shit. I see myself as a folk singer, and he produces me that way.

JT: That’s funny, because I’ve never really thought of you as a folk singer. I always more associated you with place, New York. But now that you mention it, that makes a lot of sense—especially when I think of Minor Love, which Noah also produced and which is probably your most straightforwardly folk record. What does it mean to be a folk singer in 2013? For me “folk singer” connotes—and I’m really talking out of my ass here—like Alan Lomax or Woody Guthrie; I don’t see a song like, say, Bunnyranch—which is my daughter’s favorite song, incidentally—fitting into that idea of folk. So what do you mean when you describe yourself that way?

AG: I guess I think of my music as folk music as it’s easy to sing a cappella, and I don’t really make it with any commercial reason. It’s kind of a patchwork of different feelings I’ve had over the years and it’s the story of my soul. It’s kind of a medieval tradition, and I guess I see myself as kind of a medieval person.

General (acrylic on canvas). Adam Green.

IV. WE JUST STEPPED OUTSIDE AND STARTED WALKING AROUND

JT: To get back to something you mentioned, you say that being medium-serious has done you no favors with critics, but what do you mean by that? Your reviews are generally pretty positive. Have you seen a change in how your work was received between earlier albums and more recent quote-un-quote serious ones, like Minor Love and the duets album with Binki Shapiro?

AG: I originally said back then that my songs are “medium-serious,” which is true. But then all the critics turned around and said “See! He’s not even serious! It’s shite!” And the American critics were really harsh on me until my fifth or sixth album. Actually my 3rd album “Gemstones” is, according to the statistics website Metacritic, one of the worst reviewed albums of all time. I think it’s true that critics are kinder to me now, but I think that has more to do with the passage of time than with the content of any particular album.

JT: How did the videos by Dima Dubson of you walking around New York come about (I’m thinking about “Buddy Bradley” and “Cigarette Burns Forever” among others)? I would love to see him do a similar “walking video” for the song “Rich Kids”, even though it’s an older song of yours.

AG: Dima came over one day and said, I want to make a music video of you standing in line at Shake Shake. Shake Shake is this hamburger place with a crazy, insanely long line. I was so hungover and I honestly was begging him to just do a different idea for the video. I think I asked him if I could go back to bed for a couple of hours. We just stepped outside and started walking around and all of a sudden I felt like some goofy Richard Ashcroft or something. I felt like Fat Albert walking around the hood, it was a very good vibe!

JT: The Buddy Bradley video definitely does have a “Bitter Sweet Symphony” feel to it. You can tell you really have a good time with it, despite the hungoverness. Who came up with the idea for “Give them a Token” video, where you actually take one of your own paintings on a tour of the Met?

AG: Dima came up with that one too. We were making one video a week at that time, and he said “I’m coming over tomorrow and we’re going to take one of your paintings into the Met.” It was pretty hard to get it in there!

V. IMMERSED IN A CARTOON

JT: I know you just finished wrapping up the filming of your Aladdin movie. Your work often subverts the cartoons that you’re appropriating, either in terms of the medium they are done in or in terms of the subject matter. Why did you want to do Aladdin specifically?

AG: Let me start out by saying that my Aladdin movie has nothing to do with the Disney version. It’s my own version of Aladdin where the Genie is the interface to a 3-D printer and the princess is a decadent socialite like a Kardashian. I play Aladdin and the Genie is played by Francesco Clemente. There’s a tyrannical Sultan who broadcasts a sadistic reality show and imprisons all the people in the town, and a rebel group led by Macaulay Culkin who starts an “Occupy” type group opposed to the Sultan. It’s got a really incredible cast—Aladdin’s mom is played by Natasha Lyonne and his sister is played by Alia Shawkat. There’s also a lot of other very exciting musicians and friends in the movie as well. The entire film takes place completely in a papier machê world, but with real actors, so the effect is like they are immersed a cartoon. The build was really intense for an independent film. We took four months in a warehouse with a crew constructing thirty Papier-mâché

sets and over five-hundred Papier-mâché artifacts. We filmed it in five weeks over the summer. Now I’m in the editing process and it’s a relief to be wrapped with the filming because that was one of the most stressful things.

JT: How was making Aladdin different from your filmThe Wrong Ferarri, which you made primarily on your iPhone?

AG: The Wrong Ferarri was shot on an iPhone because that’s the only way that the movie could be captured. It was a movie made on the run and the iPhone footage looked beautiful in it. It’s displacing to see a surrealist film shot on an iPhone because you normally associate the look of iPhone footage with home-video or documentary real-life subject matter. Aladdin is completely different from The Wrong Ferarri in so many ways. It required a lot more planning and crew to create this completely immersive contained world that you never leave for the entire length of a feature film. The complexity was a thousand times greater than The Wrong Ferarri. There were so many different stages from scripts to storyboards to a very intense build. And it was shot on a professional movie camera.

JT: If you had a truck full of money and could get anybody to star, what would you do for your next movie?

AG: My wife made me promise her that for my sanity I’ll never make another movie again!