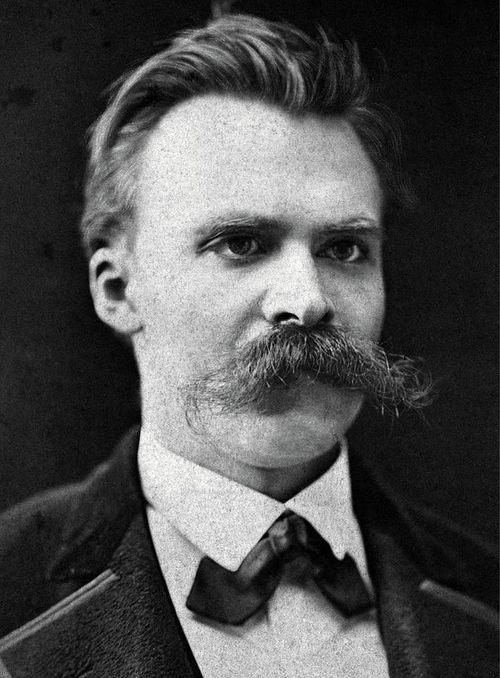

On Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche’s Ecce Homo

1.

A few years ago, I was riding my bike and thinking about the declaration “I am not a man. I am dynamite,” when I hit a pothole and flipped over my handlebars, giving a new meaning to having one’s view of the world turned over by Nietzsche. The self-anointed Antichrist never wanted to be made a holy man (sooner even a buffoon, he said) and I won’t conscript him here except as, of all things, a contemporary memoirist. Ecce Homo,the mostly forgotten autobiography in which the dynamite explodes, is a downright archetypal if extremely odd memoir. The book’s subtitle, How One Becomes What One Is, nearly saysit all: this is a story not of a life but of a self in time—how the I of the

story became the I who tells the story—and like so much of Nietzsche’s writing,

Ecce Homo was, as he said, a hundred

years ahead of its time.

Nietzsche had no way of knowing, when

he wrote the text in three weeks in

the fall of 1888, that he was about to take ill or that Ecce Homo would be his final work. At the time he was mostly

ignored, and had been best known as a former philological wunderkind. His

status grew under his sister’s careful management during the insanity of his

final decade when he was unable to appreciate it, but she withheld publication

of his own self-reflections until 1908, eight years after his death.

Ecce

Homo remains a kind of lost book from a found author; in the century since

its publication, while Nietzsche has risen in prominence and fluctuated in notoriety,

Ecce Homo has remained relatively

obscure. While books like The Birth of

Tragedy and Thus Spoke Zarathustra

are frequently referred to (if less frequently read), Ecce Homo most likely sits on your shelf only as the unfamiliar

text included in the volume of The

Genealogy of Morals you were assigned in college.

If you go to your bookshelf now and

crack that 1989 Vintage edition to page 202 you will encounter Walter Kaufmann

of 1966 making the case for Ecce Homo by

comparing Nietzsche’s—can I say swagger—to

that of his contemporary Van Gogh (“the lack of naturalism is not proof of

insanity but a triumph of style”). We have Kaufmann largely to thank for the

redemption of Nietzsche’s name after the Nazis’ attempted appropriation. But I

don’t think it’s enough to read him only as a thinker but also as, perhaps, a

liver. Because life for Nietzsche was both the root and the fruit of his

philosophy, and his philosophy appears as much in the life he recounts as it

does in what we normally think of as philosophical writing.

2.

“Behold the

man,” says Pontius Pilate as Jesus is presented for crucifixion. “Behold the

man,” says Nietzsche as he presents himself for—well, for what? What does Nietzsche

invite with chapter titles such as “Why I Am So Wise” and “Why I Am So Clever”?

Here is a supreme ironist at work, whose words always mean more than they say.

Beyond simple disclosure there is another sense to his “homo”: that we behold a

man as we’ve never seen one: Man as he might be, one who celebrates and finds

virtue in his humanness. The discussions of diet, nutrition, climate, walking,

etc., are many and become the stuff of philosophy, demonstrating the inverse of

the claim, as he writes, that “every great philosophy [is an] … unconscious

autobiography.”

Where Christ

extols heaven, Nietzsche affirms life on earth. The book’s final line reads,

“Have I been understood?—Dionysus versus

the Crucified.—” But the phrase “Ecce Homo” occurs first in Nietzsche in

the marginalia to his copy of Emerson’s “Spiritual Laws,” where he writes the

words alongside a passage that includes, “The man may teach by doing, and not

otherwise.”

Nietzsche is frequently (and rightly)

commended as a stylist, but this can be dismissive praise of an author for whom

style reveals rather than disguises character. Behold a man whose teaching is

inseparable from his doing. Behold a memoirist whose writing is inseparable

from his living. Collapsing the space between self as writer and self as

written (in the text if not outside it), Nietzsche works a neat little

ouroboric logic: his own Dionysian flair is confirmed by the text that produces

it. Such megalomania can be read as solipsism, it can also be read as apogee;

memoir invents a world in which the I

is the only possible conclusion; the text deviates from Nietzsche only insofar

as it circumscribes its world.

The longest of Ecce Homo’s four chapters, “Why I Write Such Great Books,” is a

pitiless reading of the author’s oeuvre. Whether or not he is his own best

reader, Nietzsche’s unsentimentality toward past works performs his virtue of

self-overcoming as effectively as one of his readily quotable lines: “One pays

dearly for immortality: one has to die several times while still alive.”

Singing of Thus Spoke Zarathustra,

which Nietzsche considered his (not to mention the world’s) most important

book, and to which he gives the most attention in Ecce Homo, Nietzsche writes, “Let anyone add up the spirit and good

nature of all great souls: all of them together would not be capable of

producing even one of Zarathustra’s discourses.”

This self-regard would be obscene if

it did not belong to Nietzsche. And maybe it still is, but it’s meaningful here

to recall the context for Ecce Homo.

Nietzsche was writing with manic purpose in 1888 (four books that year alone),

yet despite his sense of destiny his legacy was hardly assured. Writing that

“To become what one is, one must not have the faintest notion what one is,” Nietzsche recognized that

the memoirist, like the philosopher, was “of

necessity a man of tomorrow and the day after tomorrow.”

And yet to be constantly inventing a

new future for Nietzsche is not to turn one’s back on the past. His conception

of amor fati figures centrally in Ecce Homo, as it does in every memoir.

No writer has more resoundingly spurned self-pity than Nietzsche when he

writes, “My formula for greatness in a human being is amor fati: that one wants nothing to be different, not forward, not

backward, not in all eternity. Not merely bear what is necessary, still less

conceal it… but love it.” Which

would be a startling proclamation from someone who suffered greatly in life, except

that Nietzsche considered suffering necessary precondition for greatness. It

follows, then, that he would say, “Never have I felt happier with myself than

in the sickest and most painful periods of my life.” To actually love the past

is to affirm the necessity of life as it is. What better impulse to memoir

than: “How can I fail to be grateful to

my whole life?—and so I tell my life to myself.”

For Nietzsche this gratitude presents

in contrast to resentment, which claims a false recourse to circumstances that

do not—and therefore cannot—obtain. If things were different they wouldn’t be

the same. No one should understand contingency with respect to the self

better than the memoirist. In his introduction, Kaufmann offers this his final

assessment of the book: “‘The tragic man affirms even the harshest suffering.’

And Ecce Homo is, not least of all,

Nietzsche’s final affirmation of his own cruel life.”

Good memoirs do not blame or settle

scores. And surely Nietzsche’s does not. What generosity of spirit there is in

an unheralded writer with the courage to be thankful

for his failures: “Ten years—and nobody in Germany has felt bound in conscience

to defend my name against the absurd silence under which it lies buried… I

myself have never suffered from all this.” How many writers could mean that?

And if he indeed was suffering, as raising the issue suggests, he nevertheless

supports the possibility that for a writer the only book that matters is the

next one, and that for a person what matters is what one is currently becoming.

Reading the Nietzsche of Ecce Homo is an exhilarating—and

sometimes maddening—undertaking. Thinking back to my bike accident and the

dynamite that caused it, I find myself to be in sympathy with Malcolm Bull, who

writes in Anti-Nietzsche that “Even

though Nietzsche is attributing the explosive power to himself, not to us, we

instantly appropriate it for ourselves.”

It can feel impossible to read

Nietzsche without leaning on his style in one’s own writing, but as Nietzsche

says, “One repays a teacher badly if one always remains a pupil only.” The

drive to overcome that originates in Ecce

Homo flows off the page and fills its reader. Nietzsche compels us to see

our own lives as destinies, as narratives, and take up our own memoirs, whether

literally as writers or figuratively as subjects set loose to compose our

lives. Each of us saying one way or another, “Hear me! For I am such and such a person. Above all, do not mistake me

for someone else.”