Jane Harris on Sculptor and Installation Artist Simone Leigh

“I’m thinking about embodiment and architecture, dress and dwelling, containment and interiority,” Simone Leigh tells me as we discuss her current exhibition, Moulting, at jTilton Gallery. The stately Upper East Side townhouse seems the perfect space to foreground her ideas, particularly given the issues of race, gender, class,and taste so much of the work engenders.

“Throughout my career I’ve considered the black female body as a repository of lived experience,” she continues, “and this show is part of that ongoing meditation.” While its original title, We the Black Woman, spoke directly to that intent, Leigh’s desire to avoid narrow, essentialist readings led to the more evocative Moulting.

It’s a title that particularly animates the central sculpture in the show, Cupboard III (2015), a 9-foot high dome-like structure, made of steel, and topped with remnants of mason jar glass.

The minimalist work is based on a restaurant in Natchez, Mississippi, called Mammy’s Cupboard, the skirts of which patrons enter into to eat, and is a smaller version of asimilar work created for Gone South, a recent two-person exhibition at

Atlanta’s Contemporary Art Center (2014). As with so much of Leigh’s work, its

abstract, reductive form is imbued with layers of subtext, and a conflation of

references, that conceptually function like a skeuomorph, alluding both to

adaptation and sublimation.

It was through a 1941 black-and-white photograph by the

iconic modernist Edward Weston that Leigh first encountered the restaurant

(opened only the year before, and astonishingly still in existence), an

aesthetic document of American vernacular architecture with no apparent critique.

Holding out a tray above her skirt-cum-restaurant, the Mammy figure entreats

diners to come inside, and in characteristic Mammy servitude appears to welcome

the violation. Beyond the perverse nostalgia associated with a form meant to

signify the inhabitation of a black woman’s body, what struck Leigh most is what

she describes as “the strange sexuality of what was typically an asexual

archetype.”

Simone Leigh, Cupboard III, 2015, Steel, mason jar glass, and hemp rope, Detail view, Courtesy of Tilton Gallery

Perhaps that’s why Leigh’s sculpture lays bare its armature, and sheds the gaily painted ball gown along with all allusions to the novelty architecture: so that, once inside, the viewer becomes its embodiment—at once spectacle and spectator. The destiny to change and adapt implied by the exhibition’s

title is again evoked in the jewel-like cluster of blue tinted mason jar glass

that glints above. Calling our gaze

upward, it’s a classic representation of Leigh’s signature ability to transform

everyday materials—especially containers and vessels—into iconic

abstraction.

In addition to antebellum associations, other sources recalled in the work are the wide colonial-era

pannier skirts seen in Velazquez’s famous Las Meninas painting of 1658, as well

as the contemporary appropriation of Victorian-style petticoat skirts adapted

from missionaries by the Herero women of Namibia, who syncretically exaggerate and

subvert its form. And that’s not all: yet another source of inspiration is the

ancient Mousgoum clay houses of Cameroon, which bear

the same dome-like shape. Seen in a 1931 catalogue for the Cameroonian Pavilion

of the Paris Exhibition, these imagined recreations were ironically and erroneously presented as

ethnographic documents of the primitive. In fact their simple

structures belie quite sophisticated architectural principles. Playing with this irony, Leigh’s installation, The Gods Must

Be Crazy (2009) first adapted the Mousgoum form for a recreation of the central

cage in the 1968 film Planet of the Apes.

Of course, one doesn’t see these references in

the work; rather, they are conceptually implied: felt and suggested like

palimpsests—the skeuomorph at work again. Most of the works in the exhibition

reveal similar conflations of history and culture, modernism and primitivism, architecture

and the body. There’s a smaller sister-like dome

sculpture, Cowrie (Pannier) (2015) shown alongside Cupboard III, that doesn’t

allow entry. Made of the same steel armature, it’s topped by one of Leigh’s

signature ceramic watermelon-cowrie hybrids, a sculpture scaled to the size of

the former, and visually rendered to resemble the latter. The black dots

that pattern its sand-colored surface are achieved, the artist shares, through

an experimental process where glaze applied with a pastry knife is rock salt

fired beyond prescribed temperatures. Like the hoop skirt-cum-hut on which it

sits, the watermelon-cowrie shape-shifts between equally resonant associations,

moulting and melding in true skeuomorphic form.

Simone Leigh, Cowrie (Sage), Cowrie (Sage), 2015, terra cotta, porcelain, sage, string, wire, steel, Courtesy of Tilton Gallery

The use of abstraction to manifest this

slippery process of facture and meaning is evoked more pointedly in the

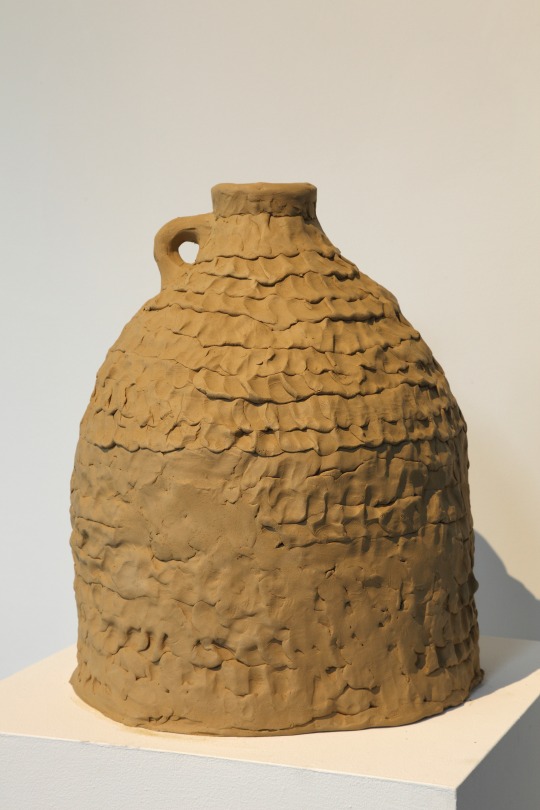

faceless “face jug” Leigh creates that sits protectively nearby. These colloquial vessels, often associated with

racist caricature, feature bulging eyes

and toothsome grimaces which are now believed to have been originally created by

slaves. Having been denied tombstones, the slaves fashioned them as grave markers to ward

off evil spirits. With characteristic finesse, Leigh’s adaption forgoes the

gruesome specter of such figuration, leaving instead on her unglazed version just

a ghostly pattern of circular thumb-prints.

Simone Leigh Jug, 2014, unfired lizella clay, Courtesy of Tilton Gallery

It’s no surprise that Leigh describes her

sculptural practice to me not just in skeuomorpic terms but as a kind of

auto-ethnography, “where art and vernacular forms serve as points of departure

in installations that combine found objects and those made by hand.” Having once been on a PhD track to become a

cultural anthropologist, I understand auto-ethnography as a type of cultural

analysis that begins in subjectivity.

It’s a form of self-study that connects personal experience to cultural

experience, evoking the old feminist maxim, “the personal is political,” as well as post-colonial critiques devised to

undermine notions of objectivity (particularly in representations of the

“other”).

I ask Leigh if this is what she means, or if she’s doing

the inverse, taking cultural tropes freighted with history and embedding in

them some aspect of her own subjectivity—that “lived experience” of the

black female body she speaks of. She replies tellingly: “I have always thought

of auto-ethnography in the first sense. However, I agree with you that I often

work in the other way you describe—’taking cultural tropes (or objects

and materials) freighted with history.’ I would say that I embed them in

my own autobiography. More and more I realize that my work is basically

autobiographical.”

Much of this autobiography is, of course, cultural, as it is

for all of us. Leigh is the child of West Indian immigrants, and some of her

material references, like the Wedgwood blue slips that have covered her

trademark ceramic plantain forms, or the brightly colored plastic buckets that

have housed them, conjure this background. But its her experiences in the world

as well that shape her work.

For example, she first encountered that catalog on Cameroonian Mousgoum houses while living in a yurt in her early 20s. Years

later, this led her to a book by Steven Nelson, From

Cameroon to Paris: Mousgoum Architecture In and Out of Africa (2007), which implied that Josephine Baker’s body was replaced by these “huts” as a new

iconography of the black female body. By 1931, over 1/3 of the human population

was under French imperial rule such that the conflation of Baker with

sub-Saharan Africa became literalized in her title, “Queen of the Colonies”. The association took hold of the artist’s imagination.

That might be why connecting the room of hoop skirt forms to

one featuring a table of refined black ceramic busts, each crowned by variously

styled Afro-puffs rendered in delicate Wedgwood blue roses, is a Baker-esque

banana skirt sculpture.

Simone Leigh, Skirt, 2015, colored porcelain, gold leaf, steel, wire, Courtesy of Tilton Gallery

Hanging just out of reach, the black glazed and gold leaf

porcelain “fruit” of Skirt dangles above us: forbidden, elusive, unattainable, and free. It’s reminiscent of a

seminal moment in Baker’s career, when—incensed by American censors who found

her topless costume too risque—she created a dagger-like version of her

legendary banana skirt, with menacing pointy forms now jutting from her busts

as well as her waist and buttocks.

A skeuomorph of the dancer’s own design, and a cutting

response to yet another attempt to control and define her exotic otherness (the

performance of which Baker always retained power over), it’s a story of

adaptation, and self-determination—themes that are essential to Leigh’s

remarkably resonant work. For in the

end, Moulting is, like all skeuomorphs, about a destiny to change, the power of

mutability, and the momentum embodied therein. Where does Leigh see her

enchanting abstraction going next? “After years of thinking of the skeuomorph

in relation to objects, I’m ready to extend these ideas to performance.”