An Interview with Joyelle McSweeney

Joyelle McSweeney is the author of two new books: a play, Dead Youth, or the Leaks, which won the inaugural Leslie Scalapino Prize for Innovative Women Playwrights, and The Necropastoral: Poetry, Media, Occults,a book of criticism in the University of Michigan Poets on Poetry series.

Her previous six books range from a story collection, Salamandrine: 8 Gothics, to The Red Bird, the first selection in theFence Modern Poets Series. She also edits, along with Johannes Göransson, Action Books, a publisher of translated works. She teaches at the University of Notre Dame.

Joyelle is endlessly inventive and aware in her treatment of language. Although we wrote to each other from Indiana to New Jersey, this interviewfelt like a Catholic art-school reunion, a corner-conversation under a

listening crucifix.

—Nick Ripatrazone

I. THE FATAL AND/OR

THE BELIEVER: During

your appearance on Brad Listi’s Other People podcast, you spoke of your

Marian devotion, and your interest in Catholic iconography. It is rare, and

refreshing, to hear a writer—particularly

a writer of work that pushes boundaries of form and genre—speak about being Catholic. Your critical

writing, to choose one genre, contains observations that only a writer

intimately familiar with this faith would include, ranging from your note that

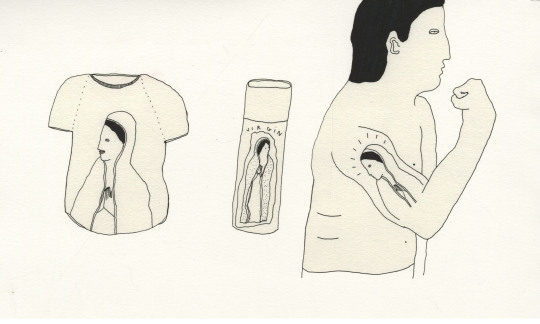

“in Catholicism, all Our Ladies are the same Lady,” to the fact that “Being able to

think among many materialisms and see them as cognates, as incarnates of one

another, is a Catholic way to think.” How has Catholic faith contributed

to your identity as an artist—your

creative and critical senses, languages, interests?

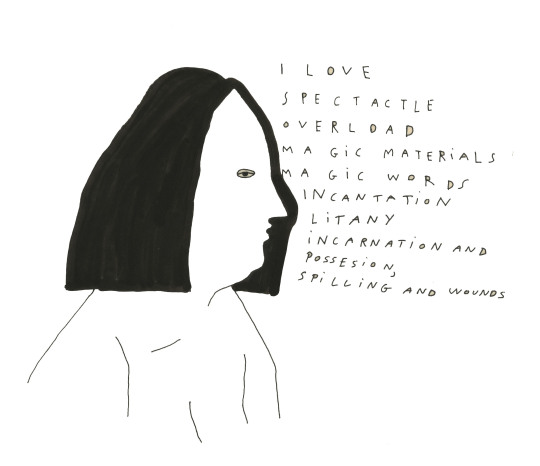

JOYELLE MCSWEENEY: My notion of art is very maximalist and souped-up: I

love spectacle, overload, magic materials, magic words, incantation and litany,

incarnation and possession, spilling and wounds. Art as a sacred event.

I’ve begun to recognize myself as a

Catholic writer because my whole notion of the image, of symbol, of art and

what it can do, has been conditioned by my immersion in Catholic culture,

ritual, and art since my earliest days. Catholicism seeped into me through

every pore. Catholicism is about seeping and pores!

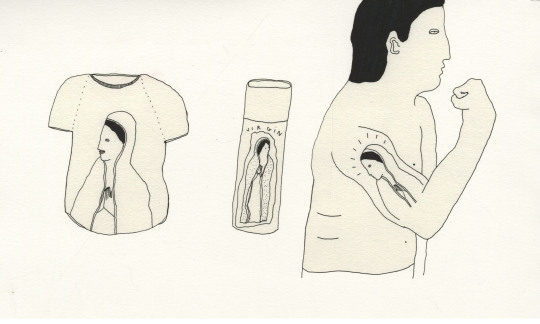

Let’s just pick one example: The Virgin

of Guadalupe. The story of the Virgin’s apparition to Juan Diego is a story about art’s revolutionary potential, about mediumicity. She appears to the peasant;

he tries to tell the Archbishop, who doesn’t believe him; so she meets him

again and points him to a clutch of flowers (roses)

blooming in December; he gathers them in his cloak and brings them to the

Archbishop; when he opens his cloak, not only do roses pour out, but she’s

transferred her sacred image to his cloak. Mary, here, is an artist who pushes

her message through medium after medium: voice, breath, air, saint, rose, paint,

cloak. She upends hierarchy and sends a tide of art moving which pushes Juan

Diego up above the station assigned to him by the local (and global) power

structure. And her sacred image is a hemispheric symbol of resilience and

resistance.

The Virgin’s image has been

reproduced in decals, spray paint, t-shirts, tattoos, you name it. It’s an

image that moves. It uses every medium: high, low, who cares. Art doesn’t care.

The Virgin also spoke to Juan Diego

in Nahuatl. So this is a force of counterconquest which arises in the

heart of the Conquest’s great weapon and alibi, the Catholic Church. This is

how Catholic art, iconography, saint’s bodies, apparition logic, technology and

mediumicity work patently and openly to counter the more repressive and hierarchical

aspects of the church.

BLVR: I want to steal your words—spectacle,

incantation, and incarnation—to describe your new play, Dead Youth, or, The Leaks, which begins with a prologue by a

character named Prologue—Henrietta Lacks, to be exact, who “died a howling

death / of cervical cancer in the colored ward / at Johns Hopkins Baltimore,

1951.” I was struck by some of her early lines: “Every Sublime gotta have its

rock bottom / every Mont Blanc its chasm / every blanc mange its spasm / every ice

berg its lower berths. / To bear the damage. / That’s me.” And later, “My body

is this play.” When I see the sublime and the corporeal discussed in such

proximity, I can’t help but think of the Catholic milieu and language you

previously mention. So, if you are a Catholic writer, is this a Catholic play?

Do you see your attention to form (and how you move between forms in your

books) as related to these considerations?

JM: Yeah, I

think you could say that! I’ve been thinking for the last few years about the

ways in which Catholic saint’s lore is really a kind of media theory, an idea

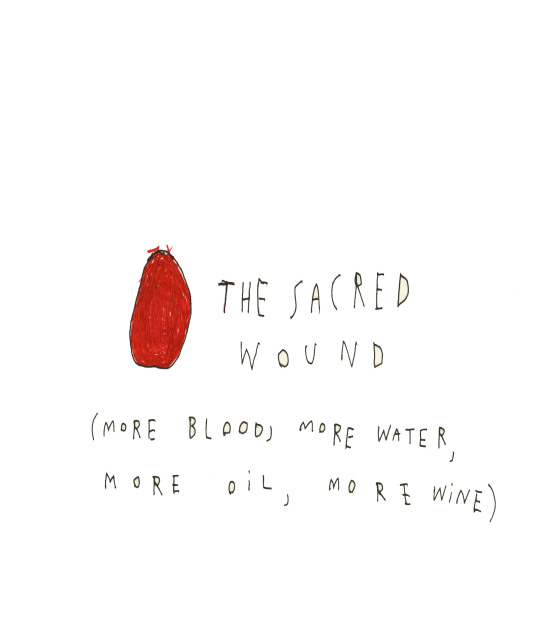

about how certain kinds of power moves from place to place. The sacred wound,

the wound that somehow keeps issuing moreness out of itself—more blood, more

water, more oil, more wine—the wound that is a womb, that is shelter, the wound

that issues occult numerologies, the wound that cannot heal, that rejects

wellness and ableness as the model we should strive for and instead places

abjectness, weakness, incompleteness, asymmetry, pain, as the indicators of

special (and outrageous) fortune. And then on top of this we have saints’

iconography, a kind of stamping of an image again and again on the world in

various media, as if it were the natural job of an extraordinary miraculous

event to make thousands of copies of itself, like a virus. My ideas about

how art comes into the world, issues from and courses back to bodies,

supersaturating, spilling, bleeding, killing, reanimating, remaking, hosting,

definitely maps onto my ideas about Catholic saints, icons, and mediation. Mary

herself is the Mediatrix, after all!

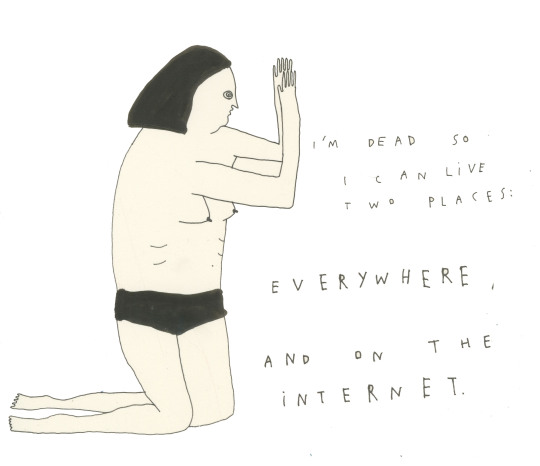

BLVR: Speaking

of Mary, there seem to be (at least) two mothers in this play: Prologue and

Julian Assange, who often reference electronic existence as a new birth

(Prologue says: “I’m dead so I can live two places: everywhere / and on the

Internet”; Julian, of course, gestated and revealed so many secrets through

code). Is this play an extension of the Internet, an electronic text? And, in a

wider sense, how has electronic life affected your usage/conception of

language?

JM: The

Internet is such a paradoxical space—it’s limitless and totally bounded,

apparently free yet corporate-controlled, apparently invisible yet surveilled,

a place of disembodiment where bodies are policed and enviolenced, a place that

is apparently ‘nowhere’ which nonetheless has a gruesome environmental

footprint in terms of server farms, factories, power consumption, heat

pollution, mines and dumps, as well as the human rights impact of such things

as combat metals used for smartphones or the labor conditions in sites where

new hardware is made and old hardware hazardously disassembled. My play exists

in and maps this space by constantly sending its motifs back and forth like packets

of information. My own writing has been maximalized by the Internet, by the

idea that poetry is media and it’s going somewhere, it’s in transit, it

operates by pulse and spectacle, interface and code. I also like thinking of

the entire Internet as the box in which Schrödinger’s cat is alive and/or dead.

The Internet is the fatal and/or.

BLVR: While

reading Dead Youth, or, The Leaks I

almost expected the prophet of electronic media—Catholic convert Marshall

McLuhan—to make an appearance. When Assange says “O dream of a crystalline

communication” and one of the dead youths responds “We Catholics believe in

transubstantiation. / Our uncanny valley runs on circuits of revulsion,” I

thought of both McLuhan and another Catholic, Andy Warhol. And even the way you

talk about the Internet space as a place of imperfect communion, how we might

be equal there but we know we are not, synthesizes these concepts in a new way

for me. I don’t mean this to be reductive, but those two Catholics—McLuhan and

Warhol—profoundly changed the way we understand media, self, and data as art.

Could you talk about the Catholic contribution toward, or Catholic symbolic

identity of, the way we communicate and commune online? And even how you engage

these concepts in your other works?

JM: I love

this series of connections, and per my response to question one, I do think

that Catholicism is already a kind of media theory, transubstantiation itself

is a media theory, the iconophilia of Catholicism is a media theory, and

hagiography is media theory. So it makes perfect sense to me. Even the

inequality of Catholicism, the insistence on hierarchy and unhappy relationship

of the one and the many that is repeated again in again in Catholicism, that’s

a kind of unhappy not-quite-binary, a system that can never come into stasis. The

virtual vs. the binary.

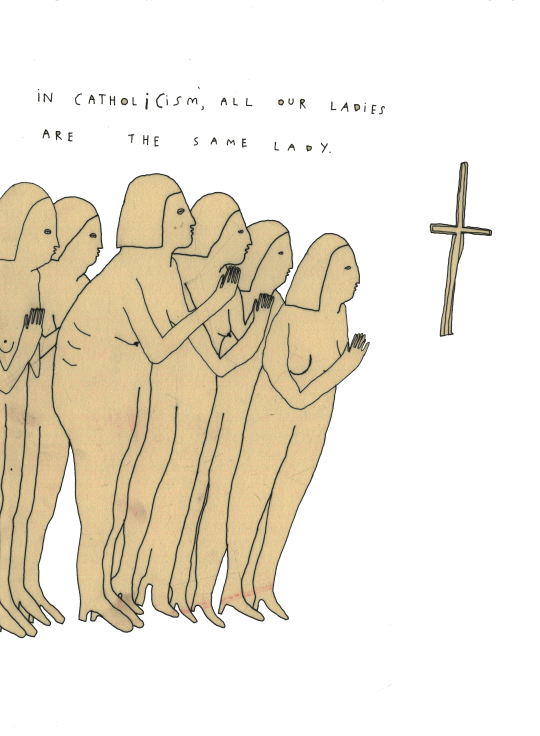

II. AN

AGE OF TORTURE LASHED TO AN AGE OF TERROR

BLVR: You also

have a book of criticism, The

Necropastoral: Poetry, Media, Occults, coming soon from The University of

Michigan Press (Poets on Poetry series).

You “give the name ‘necropastoral’ to the manifestation of the

infectiousness, anxiety, and contagion occulty present in the hygienic borders

of the classical pastoral … the term ‘necropastoral’ re-marks the pastoral

as a zone of exchange, shading this green theme park with the suspicion that

the anthropocene epoch is in fact synonymous with ecological endtimes.”

I love the breadth of writers, artists, and thinkers examined

within this book. Let’s start with Warhol, who you call a “necromancer and

fraud,” whose “time-bending movies, such as the twenty-five hour ****, affected

moviegoers variously, rendering them, like art’s victims in German

Expressionist films, entranced, asleep, or somnambulant, denaturing their

participation in chronology, that is, in a conventional, mutually compatible

social time.” Do you find the necropastoral an especially ripe space to revise

conceptions of time as it relates to art? Are there contemporary artists or

filmmakers who continue Warhol’s time play?

JM: The

necropastoral is an anachronistic way of thinking about art, a conceptual

space that hosts ‘strange meetings’, where literary time can work backwards,

impossible influences and confluences can take place. The pleasure in thinking

this way for me is that it provides a release from nationalist, patrilineal

time which is always about conserving property; the literary world has been all

too happy to copy this over, to place an emphasis on influence and conserving

masculine intellectual property, while the scholarly world relies on

periodization and national language.

Warhol changed our perception of time in art in such a massive

way that it’s difficult to even grasp the size of this reorientation. The

repetition within the artwork feels both profound and superficial, and so is

the distribution of posthumicity as the mark where media touches every face.

And he was all about grinding down and masking his own face, using the silver

wig to mask and distort the way time is read across the face.

As for contemporary filmmakers, I know there are contemporary

video artists and filmmakers working with duration in a very intellectual way,

the unbearable realtime or worse. My favorite filmmakers are David Lynch, Wong

Kar-Wai, Claire Denis, Lars Von Trier, Almodóvar—filmmakers with a very thick

non-minimalist style. These filmmakers have very different relationships to

narrative shape but in each case narrativity itself is almost something edible,

something which leaves a candy colored or acrid taste in the mouth and

nostrils.

BLVR: “Literary

canons are full of such young, dead superstars,” you say—with certain artists

of the necropastoral creating spaces of “permanent posthumousity.” It might be

a quirk of timing, but these ideas made me think of the recent demise of HTMLGIANT, and the feeling that a

certain online space and location for ideas has been lost. Is this being too

romantic about that site? Where is the necropastoral (and perhaps wider, more

“independent” literature) being sustained at the present moment?

JM: The

Internet is a graveyard, a bright malfunctioning littoral, and it is entirely

necropastoral. But the necropastoral can’t be sustained—it’s non-sustainable.

I wanted to talk about the infernal poet Sophie Podolski here,

a Belgian poet I was introduced to through Bolaño, who mentions her frequently in his

novels. Paul Legault published a facsimile translation of her great,

conflagrating handwritten poem ‘The Country where everything is permitted’ on

Amy King’s Esque, but that website

seems to be dead.

As this parable shows, the Necropastoral is an unhealthy,

spectacular network of totally imbricated live and dead tissue, live and dead

media. Dead Bolaño, dead

Podolski, live Legault, dead website. We can compare this to the Etruscan

torture of nigredo in which a living

victim is lashed to a corpse and fed until he begins to decompose along with

the corpse, as discussed in “Corpse Bride: Thinking with Nigredo” by the Iranian philosopher Reza Negarestani. The Necropastoral

is decadent, defined by decay. It is in this place where the living and dead

are joined face to face like an infernal mirror, a parody of a mirror, where we

can begin to understand what Negarestani construes as the experience of the

soul as ‘double necrosis’. “The Show” by Wilfred Owen makes another imprint of

this phenomenon, a Veronica’s cloth for this exudia. Since we live in an age of

torture lashed to an age of terror, we should be very fluent in nigredo. We should understand it on

sight.

III. SMUGGLING

IN TROUBLING NEW STRAINS

BLVR: You note

that “reading contemporary reviews of translation, one concludes that

translation must decide what its appeal will be, and that it has two

options—masterful or slavish.” As the editor of Action Books, what role do you

hope to play in reversing or engaging how we talk about contemporary

translations?

JM: For

monolingual Americans like myself, translation is exciting because it takes us

into the area of lack. Everything I have ever been taught about literature in

Anglo-American schools is that it is about mastery,

a kind of masculinist control. In the 20th century that’s been a

regime of understatement, minimalism, the almost operatically minimal sentences

of Hemingway and structures of Carver. But in fact, I don’t believe minimalism

really exists. I think everything passing as minimal is actually an outrageous

gesture of mutilation. Translation smears the categories of authorship and

mastery. It appears to do imperial work, making a work in another language

available to the hegemon, but it is counter-imperial, smuggling into the

dominant language troubling new strains.

Translation should be loud, present, palpable, it should never

pass. The hand of the translator should be outrageous and present, or duplicitous

and virtuosic, like at the end of Almodóvar’s film La mala educación which smashes through all the meta-generic strata

of autobiography and fiction when it writes across the screen, of Almadovar’s

avatar, “Enrique Goded continúa hacienda cine con la misma pasión’—Enrique

Goded continues making films with the same passion”. This word ‘pasión’ then

swells to fill the screen, writing over and retrospectively re-writing

everything the previous hour and forty-five minutes have conveyed. What is

metacritical and generically diagrammatic becomes a destroyed, interdecaying

surface to be written across, with passion as with lipstick. But even as it

fills the screen, it shows itself to be pixelated, a trick of technology,

possibly nothing.

BLVR: The Necropastoral is

populated with many forms, including lists—which I think makes it one of the

most creatively dynamic works of criticism I’ve read in a long while. In

“Expenditure: Or, why I’m going to die

trying,” you write “there’s no success like failure.” What draws you to

absences, failures, and resurrections—in the necropastoral, and elsewhere?

JM: I’m

interested in absences as abscess—the area of lack that produces an excess, an

infernal production, literature as pus. Bataille’s The Eye is a great, grotesque, comic allegory for this, as is Bolaño’s Mauricio ‘The Eye’ Silva. We can go back to Catholicism on this

one—the stigmata, the stain that bleeds, the statue that cries, the Virgin that

bears, etc. It’s a kind of impossible math, like the way the digital logic of

the Internet is constantly shedding so much affect—lust, greed, cruelty,

passion, and possibly nothing. AKA the Virtual.

See more of Jos Demme’s work on Instagram.