In which Stuart David writes about the beginnings of his first band with Stuart Murdoch, Lisa Helps the Blind.

Alistair’s solution to the difficulties we’d faced with our first two Lisa Helps the Blind gigs was to make sure we had complete control of the environment our third one took place in. We’d got to the point where we sounded pretty good in rehearsal, but we didn’t seem able to take that sound out into the world. So Alistair’s plan was to bring the world, or as much of it as would fit, into rehearsals. He’d decided to set up a gig in his front room, for a small invited audience, and it seemed like it might work. We rehearsed a set of eight songs, including ‘Lord Anthony’, ‘Perfection As a Hipster’, ‘Beautiful’ and ‘Dear Catastrophe Waitress’, and on the evening of the gig Alistair begged and borrowed twenty chairs and arranged them all in rows facing the bay window, with a little aisle down the middle.

Stuart invited two or three people. I didn’t invite anyone. And Alistair invited the rest of the audience, which probably amounted to about twenty-five people. When they started to arrive I began to get nervous about how things would go. They were a bewildering assortment of hard rock and S&M fans, for the most part, and when I looked at the programme Stuart had placed on each seat, like the hymn sheets laid out on the pews before a church service, I didn’t think this could go well. The front of the programme featured cartoons of hipsters drawn by Stuart, and inside there was a list of the songs we would play, along with a description of each one, and a manifesto explaining what we were about. I didn’t think it had much in common with what these people were about.

We’d set up in the bay window, and gradually the audience took their seats. It was like looking out at a private memorial service for a heavy-metal god, mostly a blur of black leather and hair. And then Stuart asked everyone to stop talking, which took them a bit by surprise, and after a quick tune-up we started to play our delicate songs, about schoolkids and disenchanted ponies. I thought they might just get us killed. There was a scene in The A-Team during the Eighties, where Boy George and Culture Club had to perform ‘Karma Chameleon’ for a barroom full of rednecks. Their chances of making it through the song and getting out of the bar alive didn’t look good at the outset, but as George sang, the crowd suddenly started to get into it. They had a change of heart, and George emerged a hero from the terrifying ordeal.

That didn’t quite happen to Lisa Helps the Blind in Alistair’s living room. None of the hairy rockers began to cry, overcome by the repressed feelings they’d been head-banging away for too long. No one threw off their leathers and began to dance like a flower person. But, on the plus side, nobody pulled a knife, and everyone listened politely to what we were doing. It was a curious sight to witness. Stuart stared straight ahead during the songs, fixing his gaze on the wall at the back of the room. Alistair did his little dance, and halfway through the shirt came off. But the most impressive thing about it all was that Stuart stood and played his songs without making any compromises, or making any allowances for the obvious differences between the audience’s tastes and what we were doing. It was the beginning of an education for me. I was aware that if I’d found myself playing my own songs in front of that audience, in that setting, I wouldn’t even have expected them to listen, much less take anything from it. I would certainly have been self-deprecating between songs, making it clear that I knew they didn’t like what I was doing. But Stuart didn’t do any of that. He just remained himself, allowing the audience and band to exist in stark contrast to each other. He presented his vision to them undiluted, and it didn’t seem to matter to him whether they liked it or not. And I was slightly amazed to find you could get away with that.

Afterwards, Alistair introduced me to the guy I’d replaced as bass player in the country band. He was simply called ‘The Animal’. He said that Lisa Helps the Blind wasn’t his type of thing, but that we’d sounded quite good anyway. And we had. We’d played as well as we did in rehearsal, and for the first time in our short history, everyone had been able to hear us. It felt like the beginning of something, but as it turned out, it was actually the end. Soon afterwards, I was sitting in a café near Beatbox with Alistair, and he told me that things had come to a head for him. He said he was going to give Stuart an ultimatum. Either Stuart agreed to do things at the pace Alistair thought we should be doing them, and make a proper drive for success, or else Alistair would leave.

‘Stuart’s songs make me feel the way songs made me feel when I was sixteen,’ he said. ‘I’ve been listening to pop music for so long I always know where a song’s going to go. But Stuart’s songs always go somewhere different.’

He looked off out the window, then shook his head.

‘It’s crunch time,’ he said.

I didn’t think his ultimatum was a good idea. Stuart still wasn’t well enough to do any more than we were doing. But Alistair was adamant.

‘I have to make it soon or not at all,’ he said. ‘I don’t have the time to wait around.’

So he made his stand.

I wasn’t there when he talked to Stuart, but I heard from both of them individually that Alistair wouldn’t be working with Lisa Helps the Blind any more. It all seemed quite amicable, but now it was suddenly just me and Stuart. With the money I’d saved up from playing bass with the country band, and the extra £10 a week I was getting for attending Beatbox, I realised I could probably afford to move to Glasgow now, if I could qualify for Housing Benefit to pay the rent. It seemed like the ideal time to do it because Diane, the guitarist in Raglin Street Rattle, worked for one of the biggest landlords in Glasgow, doing viewings for flats all over the city. So one afternoon I got her to drive me round to look at some vacant rooms. There were two places I liked, both on the same street as the Art School. One of them was an attic room, a bit like I had at home but bigger, and you could stand up straight in most of it. I sat in there with Diane at the end of the day and tried to decide.

‘It’s between this one and the one down the street,’ I told her. ‘Maybe I should see the other one again.’

But she couldn’t find the keys for the other one. She’d lost them somewhere.

‘I’ll take this one, then,’ I told her. ‘This’ll do.’

And I signed some papers.

There were eight bedrooms in the flat, four upstairs and four downstairs, plus a large kitchen and two bathrooms. At the moment, there were only two people living there: Rhonda, who was a town planner, and Michael, who had the biggest room in the flat but who never came out of it. All the other rooms were ready and waiting to be taken by students when the universities opened again. I moved my meagre belongings up a few days later and settled in. It was only a ten-minute walk to Beatbox, rather than the hour on the train I’d been travelling every day, and all at once I was living in one of Glasgow’s blond sandstone tenements, where I’d always wanted to be. It was only after Alistair left Lisa Helps the Blind that I started getting to know Stuart properly, and we became friends. When I moved into my new place, Stuart was living in a flat on Sauchiehall Street, the street parallel to my own. And we went round to each other’s places to play our new songs, discovering what we had in common.

In a letter to Karn, I wrote:

‘I think you would like Stuart. He’s kind of like us. He’s always talking about Kerplunk, and Aqua Boy, and Parma Violet-type sweets, and Catcher in the Rye. And he sings songs like The Pastels and all that. And he looks like that too. So he would probably be your friend. If you knew him.’

But it was the things we didn’t like that made us realise we should keep working together. Neither of us liked most of the things that seemed to be obligatory if you were in a band. We didn’t like blues music or drugs, neither of us drank very much or smoked, and we were both anti-machismo. We were just making music because we loved songs – not to get rich or to get out of our heads. We’d both grown up listening to music on the same tinny Dansette record players without much bass and with plenty of crackle, and we thought that’s how music should sound. We’d grown up listening to different records on those machines, and we’d come up with different solutions and visions for how to go about things in opposition to the accepted way, but we were both doing things for similar reasons, from a similar point of view.

There was one marked difference between us though. Most of the people I knew at that point who wrote songs or were in bands were fully focused on finding a record deal, myself included. That was considered to be the ultimate validation that what you were doing was worthwhile. But for Stuart, all that mattered was finding a group of people who believed in his songs enough to want to be in his band. He wanted his own band more than anything else in the world.

One of his favourite groups at that time was Tindersticks, and he often spoke of how lucky Stuart Staples (the singer and songwriter) was to have all those people wanting to play on his songs. The number seemed to matter. Having a big band like that, of the right-minded people, who were desperate to play your songs, seemed to be the only approval Stuart was interested in.

For years, he’d been putting posters up in music shops and cafés, looking for potential band mates. Sometimes his posters were cryptic, sometimes just a list of bands he liked. I don’t think he’d ever had any replies – he had a clear idea of the people he’d like to find, but so far no one had come forward. Finding those people, though, had become his constant aim. It was a concept I hadn’t really come across before. Most people around Glasgow threw their bands together with whoever was closest to hand, and there were already quite a few people at Beatbox who were willing to be in Stuart’s band. But he had an ideal vision in mind and he didn’t want to compromise it.

Stuart’s songwriting became insanely prolific around this time too. He was often writing three new songs a day, and an unreasonable percentage of them were good songs. He said that the songs often started out as jokes, and then developed into something real. That seemed to perplex him, even made him sad. But he continued to think up the jokes, and the jokes continued to turn into songs and sometimes he was writing them too fast for me to learn before he’d discarded them again. I’d go to watch him doing a solo acoustic spot at The Halt Bar, or supporting other songwriters, and he’d do songs I’d never heard before and would never hear again. There was one called ‘Adidas’, which was simply a list of all the things Adidas had been claimed to be an acronym for when we were at school; another about jazz boys and jazz girls which made me stop in wonder. Many more. But most of them were never finished.

‘I think the secret to finishing a song,’ he said to me one evening, ‘is knowing what the song’s about before you start.’

That seemed to be a revelation for him, and his songs really started to take shape after that. He got a batch together that he decided he would record in the Beatbox studio if his day ever came around. We did some rehearsals with David Campbell on drums, to knock them into shape, and we waited. Raglin Street Rattle was waiting to get in there too. So were a lot of other people, but the sessions for the band in the posters on the Beatbox wall continued to take precedence. One afternoon, standing outside the metal door at Beatbox, underneath the flyover that led up into the business park, Stuart asked me if I’d be the bass player in his band, if he could ever get one together. I said I’d help him put his band together, help him to get it going, but that I had my own band and my own thing to be doing.

‘I’d really like you to be in my band,’ he said.

‘I’ll help you put it together,’ I repeated.

And so it seemed that we’d come to a mixed-up agreement.

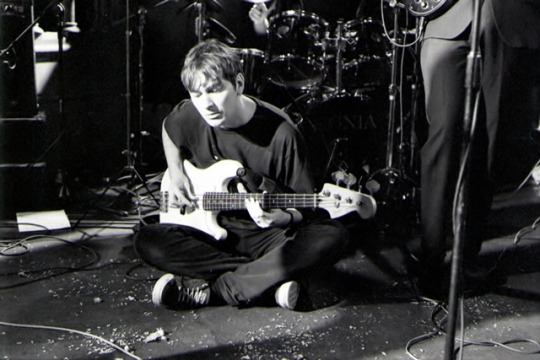

This excerpt is from “In The All-Night Cafe” by Stuart David, published in the United States on May 1, 2015 by Chicago Review Press Incorporated. Copyright © 2015 by Stuart David. Reprinted with permission of author. Image © Ellie Zober. All rights reserved.