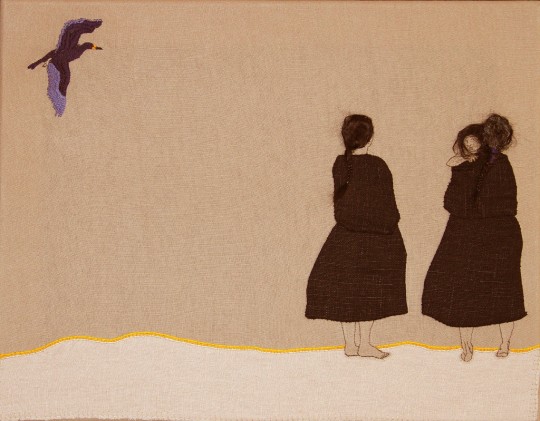

Three Women, 2013. Fabric, embroidery floss, viscose. By Emily O’Leary.

Stories of Self is a(n approximately) monthly essay series by Scott F. Parker that explores the nature of the composed self through conversations with memoirists, theorists, artists, and possibly musicians.

A Tremendous Sense of Purpose with Kao Kalia Yang

When I asked Kao Kalia Yang to talk memoir, she suggested we meet at Precision Grind, a small café around the corner from her house in Minneapolis. The space was mostly empty when I arrived early on a Friday morning. I took my coffee to a corner table and listened as “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” gave way to “Restless Farewell.” If I was looking for omens, it was a good one for the interview. Of all Dylan, The Times They Are a-Changin’ has him in his most democratic spirit, willing to lend his voice to those who have been denied one. As soon as his next album, Another Side of Bob Dylan, he would start to retreat from the explicitly political.

The accompaniment of this soundtrack was synchronistic for a conversation about Kalia’s work. Her first book, The Latehomecomer: A Hmong Family Memoir, had earned Kalia the mantle in the Hmong-American community as the voice of her generation. But not just hers. The Latehomecomer speaks as clearly for her parents’ and grandparents’ generations, those who survived the wars in Southeast Asia and found refuge in the U.S. It was the first nationally published book in the U.S. by a Hmong author and continues to be the most widely read.

I wondered if Kalia anticipated ever turning away from her political heritage. The standard reading of Dylan’s turn away from “finger-pointing songs” after The Times was that he wanted to guard against the possibility that his music could be reduced to its social function—that is, propaganda. The political stakes for Kalia, though, are, if not necessarily higher, certainly much more personal than they ever were for Dylan.

Kalia’s second book, The Song Poet, which her agent was about to send out on submission when we met, is a memoir about her father. It is structured like an album, and Kalia says was much more difficult than The Latehomecomer to craft, but it follows her debut’s model of collaboration with her subjects. She says it is a shared responsibility with her father. Whether she’ll continue to work in this vein she can’t say, but for now telling her family’s stories is the most urgent work there is for her to do.

This urgency is apparent in The Latehomecomer and it’s one of the things that most fascinates me about Kalia’s writing. She has self-consciously taken it upon herself to speak for her people. How does a person accept that kind of responsibility, and with so much grace? Dylan always resisted that kind of label. While Kalia has experienced nothing like the media swarm Dylan encountered, she embraces the role.

Right after I moved to Minnesota, I walked to Magers & Quinn one evening to look for books by local writers and found The Latehomecomer: A Hmong Family Memoir prominently displayed. At the time I didn’t know who the Hmong were or that they had a large population in the Twin Cities. But I learned soon enough the broad strokes of the history of the Hmong: forced out of southern China into Laos, conscripted by the U.S. to help fight the Viet Cong, abandoned after the American withdrawal from Vietnam and left to survive in the mountains with no safe home. Three fates awaited the Hmong: to be killed, to survive in Laos, or to escape. In 1979 Kalia’s family made it across the Mekong and to the Ban Vinai Refugee Camp in Thailand. Kalia was born there in 1980 and would know it as home for the first seven years of her life. The camp was never a long-term solution. Hmong people were sent around the world to the various countries, including France and Australia, that would take them. Most of Kalia’s family arranged to emigrate to the U.S., with some of them being sent to California and some to Minnesota. Kalia, her parents, her older sister, and some of her extended family found themselves in the John J. McDonough Housing Project in St. Paul.

To lead the life Kalia has led and not just survive but flourish is remarkable. She attended a prestigious college and graduate school, and despite enormous hardship, she has fulfilled her parents’ dream for the opportunities life in the U.S. could afford. As memoir material, this is standard gold: struggle, struggle, struggle, Redemption! The book represents the author’s personal triumph. In Kalia’s case, as in many, the book gets to be the personal triumph, as well as represent it.

What’s surprising, then, reading The Latehomecomer, is how indifferent the book is to Kalia’s personal success. The narrative does culminate with the book coming into existence, but it’s presented as the product of a collective experience. It’s a memoir where the narrator is incidental to much of the story. This flies in the face of the assumption that because memoir is a work of memory and memories are often private, the form itself must be private.

At a presentation I once saw Kalia give, she told a story about a time her mother took her to K-Mart to get lightbulbs. They couldn’t find them on the shelves, and when her mother asked a clerk for assistance, she couldn’t remember the English words light bulb, so she described a light bulb’s function: “the thing that makes the world shine.” The clerk walked away and Kalia’s mother stood there looking at her feet. Kalia decided if the world didn’t need to hear her parents, it didn’t need to hear her. The next day she stopped talking. From elementary school through college Kalia would be a selective mute, refusing except for the most basic words to speak English in public.

If Kalia speaks in diamonds now, perhaps it’s because her voice have been confined under uncommon time and pressure. Hers is not a task anyone could take up. There is something unique about Kalia that allows her to absorb, process, and distill in the manner she does—and her silencing is at the core of it.

Hearing Kalia tell this light bulb story made such an impression on me that over the subsequent years it actually worked its way into my memory of the book, my expectations for memoir overwriting the actual narrative. I only discovered this insertion, this misremembering, when I went back to reread The Latehomecomer before meeting Kalia. Some mention is made of the muteness, but it is understated (the word mute is not used) and downplayed (it is presented as a consequence of major geographical/social/cultural change that anyone might experience; the naturally climactic scenes of traumatic cause and dramatic recovery are gently elided). It was a brave decision to withhold that material, one that reveals Kalia’s trust in the value of her story on its own terms. And it’s possible that this kind of approach (letting the events largely stand on their own) is at least partially responsible for the book’s continued success. Six-plus years after publication it still sells well and remains one of the defining statements of the Hmong experience.

One of the things I wanted to ask Kalia, given her collective approach, was what she thinks memoir is. I was sure her definition would differ from mine of the self changing in time.

“Memoir for me is a collaboration of memories between different institutions, different individuals, a real opening up of experience.”

I asked her to clarify. Was it always a collaboration? In The Latehomecomer I could see that. But always?

“I like the word collaboration because it gives a spirit of a communal working together that happens, and I think that has to be the end product for memoir, many things have to come together.”

As we talked more I began to see my resistance to Kalia’s definition as evidence of the embeddedness of self in Western discourse. It’s a baseline assumption of my experience of existing that stuff happens to me. Even if I reject the idea intellectually, experientially it remains. A life in this framework essentially comprises the experiences one remembers, and a memoir is such a narrative as literature. What Kalia was talking about was something else entirely.

“In my culture when people tell stories it’s always communal stories. Stories that have been passed down, gifts and tokens, observations from someone else’s life. Very rarely is a story a personal narrative. So it’s the first way for me to approach story. If I tell a story of my life it feels very tiny. When my uncle tells me a story from the past it feels like the story belongs to me. When I was writing the book I knew I was writing the Hmong experience, I knew I was writing the Hmong story, I knew it would be shared. And that made it easier. It was our lives, and I wasn’t going to be the only one standing in the mix of that.”

As a lover of memoir, I want resist the idea that an individual life is tiny by saying the value of memoir lies less in what one’s story is than in how that story is told. But in a culture where stories and lives are held less individually the concept of “one’s story” begins to bend. If stories are shared, what does it mean to say some are mine and some are yours?

“One of the first things I learned was to go after the big story. That was the story I loved, the story that made my heart bigger. It’s easy to fall into the trap of your self, especially in memoir. I knew that the story was bigger than me, and that opened my heart up in a very real way.”

Curse (Detail of Roots), 2013. Fabric, embroidery floss. By Emily O’Leary.

The music by now had switched over to Common’s Be. I asked Kalia, “How is voice like home?”

“I have two different voices. I speak Hmong. English sounds different in my ear. To be home is to live in comfort and security, to be a slob in language if you want. When I go into English it’s a language of outside, it’s the outside world coming in. English allows a different terrain to explore. The Hmong are one of the most linguistically isolated people in America, especially my parents’ generation and before. In English they have no voice. Hmong for me is the language of my mother and father, the language of love and care and comfort. English is brave. And in my house I don’t have to be brave. I can be messy, I can be slobbish, I can be young. That’s home.”

I wanted to ask Kalia about voice and home because, again, her book literalizes those memoiristic searches for these things. Nabokov in Speak, Memory and Proust use memory as a way of returning to lost times and places. Memoir (and reading In Search of Lost Time as one) in these cases is about a longing for home and an exploration of that longing. In The Latehomecomer the situation is different. Kalia is not longing for a home that is lost to her, she’s longing for a home she, like everyone she knows, has never had, a home she hopes, through the book, she’ll find.

From the book: “We didn’t come all the way from the clouds just to go back without a trace. We, seekers of refuge, will find it: … If not in life, then surely in books.”

According to Czesław Miłosz, “Language is the only homeland.” Kalia is at home in Hmong, but the Hmong language has no home. English, which has a home here (if not everywhere), becomes the language with which she can build a new language-home for the Hmong people. The simultaneous freedom and responsibility of home-building have compelled Kalia since she was a girl. In school, she was writing before she knew how.

“I wrote cursive circles on the sheets of paper, careful to keep my ‘words’ between the blue lines on the page. Slowly the thin notebook filled with make-believe stories that I had been told, with stories that I wanted to tell about how it had been in Ban Vinai Refugee Camp, and stories about the times before I was born… . It was mysterious and incredible the places that I could have come from because Hmong people didn’t have a home, which meant we could have come from anywhere at all.” Already we see Kalia inventing her own language—and giving it away.

The need for home may have been palpable, but needing isn’t finding. I asked Kalia how she thinks she became the person who could tell this story.

“I was born at the right time. I had been privileged enough to be in a place where I could. So many Hmong writers began their journeys before mine and they’re still struggling to find the balance between a job that pays, the books to read that will feed their hearts and imaginations, and the time to push it out. I’m incredibly fortunate.”

Kalia is quick to point out the contingency of her existence as well as of her accomplishments as a writer. She writes, “If the sun had hidden behind a cloud, if the sound of wild game had come from a different direction, then perhaps I would still be flying among the clouds.” Everything that came before makes possible everything that comes after: “A young woman emerged from the moldy house, a young woman who wanted to be a writer and tell the stories of a people trying at life, to look for all the reasons that called life from the clouds.”

More on those clouds below, but first: one of Kalia’s hopes for her work is to ingrain the Hmong story in the American consciousness. But how many stories ever get ingrained? Another St. Paul writer, F. Scott Fitzgerald, wrote one in The Great Gatsby, a story which maintains in the culture for its sophisticated engagement with the American Dream. The book’s interest was personal for Fitzgerald. He was famously obsessed with money and class. When he received news that his first book, This Side of Paradise, had sold he ran down the middle of mansion-lined Summit Avenue celebrating.

There’s a scene in The Latehomecomer when Kalia’s family is out looking for a new home and her father drives them down Summit looking at the houses, including in all likelihood the one Fitzgerald eventually lived in. “We were awed and discussed the merits of owning the structures before us, humongous and intimidating, haunting and invincible.” Still, the reason her father drove them on Summit: inspiration.

The American Dream is a pre-packaged narrative that can readily be applied to Kalia’s life. From the time her family arrived “a puddle of wet rags on the doorstep of America” to literary success it’s been an advance for Kalia from one station to the next. I wondered what she thought of the term.

“I say that sometimes because it allows me to do another kind of work. I allow my parents to believe that better days are going to come. They look to me to bring them good news. I go into the world in search of it every day. I find the flower that blooms so beautifully it makes my heart stop, and I call my mom because there is no other good news to tell her. I saw this flower and it’s incredible and I’m going to try to get you to see it. I do that every day. Is that the American Dream, a heart that continues? When we’re in the car I point to my daughter everything that I think is beautiful, the sunshine on a leaf. I want her to believe in it.”

If the American Dream is an optimistic perspective one must intentionally cultivate, what happens when reality intrudes? This is the flipside of my question. If Kalia is living the American Dream, what of those who are not?

“My brother was born in America. His life is very different from my own, his struggles are different. His experience is as valid as my own. His pain I feel so keenly. His story I’m still learning how to tell. Is he living the American Nightmare? I don’t want to accept that. And if I can’t accept that, then I can’t accept that I’m living the American Dream. If my life is a dream of America, we have to learn how to dream better, we have to learn how to dream deeper. I feel so much gratitude for the opportunity to live, for the belief in my heart that I can make some of my mom and dad’s dreams coming true, keep them believing in dreams. If my life is the American Dream, then the American Dream becomes nothing more than the ability to keep those around you dreaming, those that you believe in believing. My younger siblings, they look at me and I want them to believe anything is possible. But they see me cry, they see me fall, they see me stumble. I feel my brother’s pain so keenly, and I think he feels my success so keenly. This can’t be the American Dream or my brother would have more opportunities, those boys that threw the punches would halt.”

I want to know where Kalia finds the reserves to support her parents, her brother, her people in this way and how she’s able to maintain her attention on the beauty in life.

“If I don’t I would die from the sorrow, because of the pain. I feel things so keenly.”

She offered to tell me a story.

“Not too long ago, I gave a big talk and it went well. After, Aaron [her husband] and I went to the bowling alley to watch football because I’m a fan of the Vikings. And I went to the bathroom and I came out and there were two women standing there waiting. There was only one stall. They looked me up and down and didn’t use it. They just left. I felt so horrible. I’d just gone and given my heart to cross lines like that and make a more beautiful world. The power I harnessed from five hundred people fell in the face of two. I broke down, I had to leave.

“Aaron didn’t know what to do. When I told my brother about it, he said, “haters are gonna hate, let it roll down your back.” Knowing what my brother has gone through, hearing those words from him, the next day it felt different. I knew I had to do better. If I could go back to that moment I’d say, ‘Excuse me, why aren’t you using that bathroom?’ Force a confrontation. But I didn’t have that energy that night. So it’s an up and a down.”

Isn’t that a pretty high standard to hold yourself to, I asked. Not to mention the risk of the confrontation.

“I think too many people have already taken too many risks to make me possible. I shouldn’t have happened but I did. I couldn’t do it that night, so I go back and write it down so I can meet them in different circumstances. I write these stories because I’m passionately trying to do something. I’m not writing to create a book for a book’s sake. I’m not interested in being that kind of writer. One of my teachers said, ‘You can’t just write beautiful words that mean nothing. It’s a chase after meaning.’”

Now back to those clouds.

The Hmong believe that babies are in the clouds and that they choose to come to Earth to enter a particular life. It’s a neat idea. Unlike the Western myth of tabula rasa, the Hmong myth brings with it a sense of purpose in life: each of us chose the life we’re living.

In a way, this choosing inverts one of the causal riddles at the heart of memoir. The baby chooses a future and in choosing shapes its present. The memoirist chooses a past and in choosing adopts a new stance in the present.

I asked Kalia whether the past she chose to write in The Latehomecomer is the same as the future she chose to live when she was in the clouds. Basically, this is a question of artifice that could be put to any memoirist: are we reading the real you? And the answer, because memoir filters life, must always be yes and no. Yet the metaphysical context for The Latehomecomer makes this a more nuanced and, it seems to me, profound question.

“They’re exactly the same person. I came down to the people who would be my parents, my grandmother, my uncles because I wanted to live my life with them. So much of my work as a memoirist is about preserving those lives because they’re more than my own. One doesn’t write just of one’s self in one’s stories; you write about the stories you share, the stories that you take on, and I’m writing about those lives that compelled me from the clouds. I’m writing about the woman with the wide feet, the lopsided walk, about the girl and the young man. I’m writing about my mother who’s learning how to age still with the torch of girlishness still holding high. And my father. I’m still writing about them. They’re the reason why I came and they’re the reason why I write. What I’m doing now takes a skill set, but the heart is the same heart. I’m not sacrificing anything. I’m not forgoing anything.

“The life I’m living is the life that called me from the clouds. I feel a tremendous sense of purpose. I think a lot of writers get lost in the story, they get lost in the process. I’m not lost. I’m looking.”