div< div=””>The hero is a feeling, a man seen

As if the eye was an emotion,

As if in seeing we saw our feeling

In the object seen…

—From “Examination of the Hero in a Time of War” by Wallace Stevens

I had been carrying my father’s glasses with me. He was in his casket, looking like no one I knew. I slid them on his face.

“That looks more like him,” my mother said.

But that’s not what I wanted. I wanted him to see me.

I was eighteen when he died at eighty, but as I stood at his casket I felt like I was four—the year I was when he lost his left eye to a rare disease. I remembered, for the first time, the night he told my mother, “I close my right eye and I can’t see Jeannie.”

“Would you like to keep your father’s glass eye?” the funeral director interrupted.

I looked at my father, his eyes glued shut.

“No,” I said. “I couldn’t.”

Just as I have no idea why my father died exactly—“He had so many things wrong with him,” my mother tells me—I have no idea why he lost his eye.

“Degenerative eye disease maybe?” she says on the phone. “Advanced glaucoma? The doctor said it happens to something like one in a million people.”

“What happened exactly?”

“Your dad’s tear ducts were closed and clotted with blood, and the doctors couldn’t get them to drain. I don’t know what you call it.”

“Try to remember.”

“I can’t.”

Doctors called the pain in his left eye “excruciating,” but he never complained—not to the doctors, not to my mother, not to me.

“How did Dad accept the loss of his eye?” I ask my mother. “Did he accept it?”

“Yes, I think so. I don’t know if you remember how he used to throw up constantly and couldn’t walk up and down the steps. We had that sofa bed in the living room and he had to sleep down there all the time. It was like a pressure that built in his eye. He either had to live with it or have the eye taken out. So he said, ‘Let’s have the eye taken out.’ Do you remember when he went?”

I remember the hospital felt a long way from home.

I remember we stopped on the way and ate hamburgers in what used to be a bank. Chandeliers hung above us.

“Do you remember the priest in his room, the other patient?” she asks.

“No.”

“The priest told your dad, ‘I don’t know if I could accept that,’ and your dad said, ‘Well, what makes the difference if I accept it? It’s not going to change it.’ Your dad was very brave.”

Two years after he died, I wrote a long poem—more than one hundred and twenty lines—that shifted between scenes of my father losing his eye and scenes of him dying. I called it “The Glass Eye Poem.” I wanted to show how great he was; instead, I simplified him.

After he died, a selfish thought haunted me: he can’t see me.

A month before the poem was due, my professor told me that it was done.

But I read, and reread my poem, searching for ways to improve it.

“I am here trying to hold onto him, / but all I can hold is his eye.”

The poem neglected who he was. Yet I don’t know how to explain—within the space of a poem or an essay—his character, or the intensity of my love for him.

I remember after he died, someone asked if he and I had been close.

“What do you mean?” I said.

“He was so old when you were born.”

Because he was almost sixty-two when I was born, he was able to retire from his painting job at the hospital where he and my mother met. After my mother returned to work, to her job in medical records, she cried because I would cry without him near me.

“You only wanted him,” my mother says. “You wouldn’t stop crying unless you had him. You wouldn’t let me put you to bed, read you stories. You were with him all day. You were used to him. I’d call from work and ask what he was doing. ‘I’m making Jeannie animals out of paper.’ Or ‘I’m teaching Jeannie how to twirl spaghetti.’” She pauses. “He saw how unhappy I was. ‘She needs her mother,’ he told me. So I agreed to quit working. You were a year old. I was worried about money, but he said we could make do on his retirement and Social Security.”

And we did. No one could say I did without. I had dogs and turtles and bunnies. I attended private school. I practiced ballet at a dance studio near the lake, learned how to paint fish and birds on Saturdays in an artist’s home. Every month, I accompanied my father to the bank where he bought savings bonds in my name “for your college someday,” he said. Only later would I notice the holes in his socks.

Do you see why this is hard?

More than twelve years have passed since my father died, and for more than eighteen years I have heard voices.

“Pick up the knife and cut your eyes out,” they have told me. “You’re supposed to know what it’s like.”

Ashamed, I never complained about them—not to my doctors, not to my parents, not to myself. “Your father didn’t complain,” the voices have said.

I understand their logic, or think I do: they want to remain a secret. But to assume that they possess logic is to indulge what others tell me is fiction.

And yet they sound real.

I first began to hear them when I was eleven, or maybe twelve. I simply heard my name repeated. I tried to think nothing of it.

In college they began to repeat my name with anger. I tried to think nothing of it.

One month before I graduated, I hallucinated my eyes had fallen out. I thought something of it, and admitted myself to the hospital.

After that, I lost any confidence I might have had in my intelligence. If I could be tricked by my own mind, then what good was it?

That’s the most frightening part: my thoughts thinking without me.

“Jeannie’s stupid,” they have told me. “Yes, she’s stupid. Jeannie is stupid.”

Sometimes I hear them as I write, as I did when I began this essay. I never thought that the voices would become part of it.

I thought that I would research the history of artificial eyes. I would intellectualize the eye because that, I decided, would not be stupid.

In 1922, the year my father was born, one in four hundred Americans owned at least one glass eye. At that time all artificial eyes in this country came from Germany and were made of cryolite glass. Eye craftsmen, usually peasant artisans living in the Black Forest or some other remote region in Germany, toured the United States, setting up their services for several days at a time in one city after another where they made artificial eyes and personally fitted them to wealthier patients. Most patients, however, could only afford pre-made eyes, which rarely matched their counterparts in color or size.

But by the start of World War II, artificial eyes were no longer made of glass in the United States. German goods were limited and German glass blowers no longer toured the country. The United States military, along with a few private practitioners, developed a less expensive method of fabricating artificial eyes, using oil pigments and plastics. Since then plastic has become the preferred material for artificial eyes in the United States.

My father’s eye was plastic, but sometimes I call it glass.

Glass implies the ability to be broken.

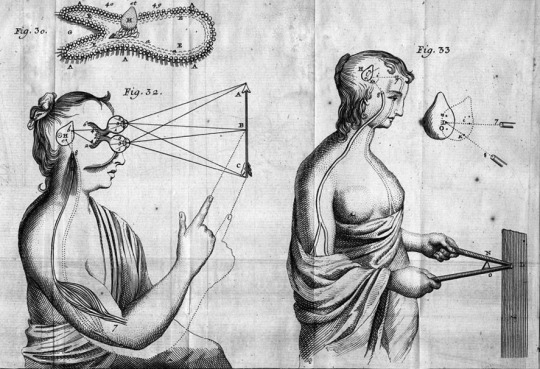

Here at my writing desk sits an anatomical model of the human eye. If I lift off the eye’s upper hemisphere, I can see painted veins that look like blue and pink branches. The white body inside the eyeball is mostly transparent, mostly scratched.

According to the gold label on the pinewood stand, the eye was made by a Chicago company that—I have since learned—also manufactured maps and globes. It makes sense; my father’s eye is my world.

That metaphor delivers an idea to me in fragments: the artificial, artifice, the artifice of fiction. Just as novels can teach us what it means to be in the world, an artificial eye can teach us what it means to see. Do we care more about seeing, or how we are seen?

And what about the artifice of wholeness? Just as my father’s eye was not real, the voices are not real. But they sound real—male and female voices speaking sometimes to me, often about me. My father hid his disability with an artificial eye. For more than ten years, I hid mine with silence.

In the nineteenth century, artificial eyes often looked crude, unnatural. Because physicians considered the surgical removal of eyes dangerous, most artificial eyes were curved shells of glass or enamel that rested on the diseased or injured eye. Their sharp edges damaged the surrounding tissue and restricted movement.

Novelists such as Anthony Trollope, Georges du Maurier, and Charles Dickens exploited this. They flattened their one-eyed characters into grotesque and sometimes cruel oddities.

In Trollope’s 1859 novel The Bertrams, the one-eyed Miss Ruff is an ugly spinster. One female character says of her, “Miss Ruff is horrible. She has a way of looking with that fixed eye of hers that is almost worse than her voice.” Another says of Miss Ruff, “I wish she had a glass tongue as well, because then perhaps she’d break it.” Men pine after The Bertrams’ beautiful female lead Caroline Harcourt while Miss Ruff—like many nineteenth-century women with physical disfigurements—remains marginalized. But the eye is not her only lacking trait; she is rude and unladylike. She plays cards aggressively, “emitting fire out of her one eye.” More caricature than character, she contributes nothing to the plot. The Bertrams could have survived without her.

Likewise, George du Maurier’s 1898 novel The Martian could have done without the one-eyed Monsieur Laferté. Laferté “was not an Adonis, and could only see out of one eye—the other (the left one, fortunately) was fixed as if it were made of glass—perhaps it was—and this gave him a stern and rather forbidding expression of face.” Yet he married a lovely, “gentle” wife, had beautiful children, and was elected mayor of his town. “The republican M. Laferté (who was immensely charitable and very just) was very popular indeed, in spite of a morose and gloomy manner. He could even be violent at times, and then he was terrible to see and hear.” But given Laferté’s minor role, we rarely see or hear him.

Dickens, however (who fathered enough minor characters to populate a small town), assigned a one-eyed schoolmaster named Mr. Squeers the lead role in the 1838 novel Nicholas Nickleby. His defining feature is a menacing glass eye: “He had but one eye, and the popular prejudice runs in favour of two. The eye he had, was unquestionably useful, but decidedly not ornamental: being of a greenish grey, and in shape resembling the fan-light of a street door. The blank side of his face was much wrinkled and puckered up, which gave him a very sinister appearance, especially when he smiled, at which times his expression bordered closely on the villainous.” Squeers accepts mostly illegitimate, crippled, or deformed children into his school for a hefty fee, and starves and beats them—with his cruel wife’s assistance—while pocketing the money for his family’s purposes. That he himself is deformed, and beats deformed children, reveals his inner conflict; he hates deformity, hates himself.

The word “louche” means “dubious,” “shady,” “disreputable.” It also comes from the Latin “luscus,” which means “blind in one eye.”

The past several years, I have tried to write a book called The Glass Eye, in which I conflate my father’s loss of his eye with my loss of him. The central question: How does my father see me? How is an essential word. Without How, there is no question, or rather: it allows for the possibility of no father.

I remember almost nothing before he lost his eye. It is as if my life begins there.

I even remember a visit to my father’s eye doctor when I was four, though I remember only one visit; my mother tells me there were more.

“We brought you with us because your dad didn’t trust anyone to watch you,” she says, “and I had to drive him. He was in so much pain, but he wouldn’t tell anyone he was in pain.”

I remember my father sitting in the middle of a white room, peering into a coal-black lens machine with his left eye. A circle of lights shone over him. I sat at my mother’s feet with a coloring book.

His doctor leaned cautiously into him, prodding the eye with a wand of light.

I remember the doctor leaving the room and returning with a nurse. She motioned for me to follow her into the hallway. I did, and she closed the door behind us.

“Your grandfather is a brave man,” she said.

She told me to stay where I was and disappeared into another room before I could say, ‘He’s my dad.’

I cracked open the door and looked at him. The doctor was pressing a needle into the eye, and my father didn’t flinch.

Not all fictional one-eyed characters are villainous. In Mark Twain’s 1872 novel Roughing It, a pair of one-eyed women—Miss Jefferson and Miss Wagner—possess basic human decency. Like Miss Ruff, however, they are minor spinsters.

Miss Jefferson lends her glass eye to poor Miss Wagner to receive company in. But the eye is too small and twists around in her socket, staring aslant while her real eye looks straight ahead. It makes the children cry: “She tried packing it in raw cotton, but it wouldn’t work, somehow—the cotton would get loose and stick out and look so kind of awful that the children couldn’t stand it no way.” The dark slapstick humor is tinged with kindness; when Miss Wagner loses her glass eye, other characters come to her assistance. The narrator tells us that Miss Wagner “was always dropping it out, and turning up her old dead-light on the company empty, and making them oncomfortable, becuz she never could tell when it hopped out, being blind on that side, you see. So somebody would have to hunch her and say, ‘Your game eye has fetched loose. Miss Wagner dear’—and then all of them would have to sit and wait till she jammed it in again—wrong side before, as a general thing, and green as a bird’s egg, being a bashful cretur and easy sot back before company.” Yet we never see how Miss Jefferson and Miss Wagner feel about their glass eyes.

“How did Dad feel when his glass eye fell out?” I ask my mother.

“He cared about how it affected you,” she says. “One night we were eating spaghetti and meatballs and it fell out and rolled across the kitchen table. You said, ‘Dad, your eye popped out’ and kept on eating. I’ll never forget it. You must have been seven or eight. He felt so bad about that—for your sake.”

“I don’t think it bothered me,” I say.

“He worried it bothered you.”

“Your father didn’t complain,” the voices remind me.

I see now what I clearly am avoiding: fictional characters with mental illness. Of course I resist researching literary portrayals of characters who hear voices. Maybe I’m afraid of seeing my experience inaccurately portrayed. Or maybe I’m afraid that someone can portray my experience better than I can.

And yet why do I think that I can determine if a character’s loss of an eye is accurately portrayed? I know nothing of my father’s experience. I infer it based on my experience with an invisible illness.

While Trollope, du Maurier, Dickens, and Twain’s novels feature one-eyed characters whose glass eyes appear clearly fake, the technology surrounding artificial eyes was improving thanks to Auguste Coulomb Boissonneau, a manufacturer of artificial eyes in Paris. Boissonneau, a real man, makes an appearance in fiction regarding his artificial eyes.

In Blanchard Jerrold’s 1860 adventure novel The Chronicles of the Crutch, Mr. Babbycomb, on board a ship traveling the Atlantic, tells other passengers about the great talents of Boissonneau.

“M. Boissonneau of Paris, constructs eyes with such extraordinary precision,” Babbycomb says, “that the artificial eye, we are told, is not distinguishable from the natural eye. The report of his pretensions will, it is to be feared, spread consternation among those who hold even wigs in abhorrence, and consider artificial teeth incompatible with Christianity; yet the fact must be honestly declared, that it is no longer safe for poets to write sonnets about the eyes of their mistresses, since those eyes may be M. Boissonneau’s.”

Boissonneau reportedly supplied symmetrical eyes suitable for insertion into either socket. An 1852 edition of the TheLancet London: A Journal of British and Foreign Medicine calls Boissonneau’s artificial eyes “so perfect, that art cannot be distinguished from nature.”

But the woman who painted my father’s eye told me that no one’s eyes match perfectly. His new left eye needed to be slightly different from his right.

I was four years old, and I remember spools of red thread, shiny blades, small jars of paint, and brushes thinner than my watercolor brushes sat at her long desk.

As she painted, she looked at my father’s real eye, then down at the glass eye, then back at his real eye.

“What do you think?” she asked me when it was finished.

I looked at my father, then down at his new eye.

“Am I remembering right?” I ask my mother. “Did I watch someone paint Dad’s new eye?”

“You watched,” my mother says. “And I remember what you said when it was done: ‘It looks real.’”

Despite improvements in the skill and craftsmanship surrounding glass eyes, prejudice about them persisted into the twentieth century. In a 1904 editorial, The New York Times claimed they possessed “sinister and variously disturbing attributions.” The article called them “deluding toys.” It said, “The most misleading and malign aspect of this apparently innocent object is that the expression it wears bears no correspondence with the sentiments which may happen to be moving the spirit of its wearer. The artificial eye may look quite friendly while the bosom of the one whom it decorates is a whirling gulf of rage and wickedness.”

Ralph Ellison in Invisible Man uses an artificial eye as a metaphor for a man’s utter ignorance and cruelty.

Published in 1952, the novel is narrated by a nameless black man who becomes the chief spokesman of the Harlem branch of the Brotherhood. The narrator proclaims in his first official speech with the Brotherhood that the white authorities “dispossessed us each of one eye … so now we can only see in straight white lines. We’re a nation of one-eyed mice.” He says, “they’ll slip up on our blind sides and—plop! out goes our last good eye and we’re blind as bats.” Brother Jack, a former soldier, and the leader of the Brotherhood, wears a “buttermilk white” artificial eye, but the narrator only learns this near the novel’s end, when it falls out. The narrator had viewed Brother Jack, a former soldier, as a visionary. Brother Jack once held up the eye, literally, as a sign of pride: “You don’t appreciate the meaning of sacrifice. I was ordered to carry through an objective and I carried it through. Understand? Even though I had to lose my eye to do it.” As the novel unfolds, the narrator comes to understand that Brother Jack fails to see African Americans as individuals; he sees the narrator as simply a tool for the advancement of the Brotherhood’s goals. Brother Jack, in the narrator’s widened eyes, diminishes into “a little bantam rooster of a man.” His one eye symbolizes his moral weakness. Once the Brotherhood’s focus shifts, Brother Jack abandons the African American community. The disillusioned narrator retreats into a basement lair; he sees himself as invisible.

My father’s eye may have made him slightly more fragile to me, but it also symbolized his bravery.

The only novel that possibly nears my father’s experience of losing an eye is The Song of the Lark by Willa Cather. There, a Hungarian piano teacher, Harsanyi, is blind in his left eye. He defines himself by his piano career, which he likewise defines by his glass eye. His personal conflict is not about how he plays the piano without an eye, but about how the audience sees him as he plays: “He believed that the glass eye which gave one side of his face such a dull, blind look, had ruined his career, or rather had made a career impossible for him.”

Cather often makes mention of Harsanyi’s “one eye,” his “gleaming eye.” “Harsanyi’s eye flashed.” She describes his good eye as “full of light and fire when he was interested, soft and thoughtful when he was tired or melancholy. The meaning and power of two very fine eyes must all have gone into this one—the right one, fortunately, the one next to his audience when he played.” It “sometimes seemed to see deeper than any two eyes, as if its singleness gave it privileges.”

He lost his left eye when he was twelve, the result of an explosives accident in a Pennsylvania mining town. Harsanyi, like my father, accepted the loss without complaint: “He held no grudge against the coal company; he understood that the accident was merely one of the things that are bound to happen in the general scramble of American life, where everyone comes to grab and takes his chance.”

When my father was dying, I ran photographs along the rails of his bed, scenes I didn’t want him to forget: him reading a book to me despite the white patch over his eye; him pulling me in a wooden sled; him clutching me on his lap and looking off somewhere as if he knew what was coming.

In H.G. Wells’ novel The Food of the Gods and How it Came to Earth, a character’s glass eye is revealed only after his death. “It stared out upon the world with that same inevitable effect of detachment, that same severe melancholy that had been the redemption of his else worldly countenance.”

I only became obsessed with my father’s artificial eye after he died. Thinking about him through metaphor is easy; encapsulating who he was in plain language feels impossible.

In my darkest moments, I think about the inside of his coffin: Is it nothing but ashes, a suit, and an artificial eye?

In José Saramago’s novel Blindness, the story of an unexplained mass epidemic of blindness affecting the inhabitants of an unnamed city, a conversation between two men, one of whom wears an eye patch, comes down to a question of aesthetics: “I’ve never asked you why you didn’t have a glass eye instead of wearing that patch, And why should I have wanted to, tell me that, asked the old man with the black eyepatch, It’s normal because it looks better, because it’s much more hygienic, it can be removed, washed and replaced like dentures, Yes sir, but tell me what it would be like today if all those who now find themselves blind had lost, I say physically lost, both their eyes, what good would it do them now to be walking around with two glass eyes, You’re right, no good at all, With all of us ending up blind, as appears to be happening, who’s interested in aesthetics?”

My father wore the artificial eye for me.

“He was old,” my mother reminds me. “He knew kids were making fun of you for that. Just think what they would have said if they had seen the eye patch.”

I worry about what people will think of me if they know I hear voices.

I have never seen bodies behind the voices, but that does not make them feel any less real.

At my worst, they say and can make me say, “Jeannie’s going to die. Jeannie deserves to die. Jeannie’s going to kill herself.”

The last time I was hospitalized for a “severe psychotic state,” my doctor asked me if I was still writing about my father.

“You always seem to be writing,” the doctor said, “and I think it’s making you sick.”

Sometimes the voices tell me that The Glass Eye is pointless: “He can’t see you.”

“I can’t see out of my left eye,” I told my father after he began wearing his glass eye. I must have been five, maybe six. “Do you think I need a glass eye?”

“Are you lying?” he asked gently.

He lifted my chin, looked into my eyes, and I apologized for my first lie.

“I want to be like you,” I said.