An Interview with Artist Roger White

Roger White is an artist and writer who lives in New York and Vermont. His oil paintings and watercolors use the traditional techniques of still life observational painting to create gentle imagery of Brita water bottles, mirrors, clothing, and abstraction. With Dushko Petrovich he co-founded Paper Monument, a journal and publisher of writing about art that replaces the academicisms and formalities of art writing with a broader, looser approach to the subject of visual culture. Recently, he published his first book, The Contemporaries, a panoramic view of the art world that serves as both an introduction to non-art folk and a refreshingly balanced approach for any art insiders who have lost perspective on the bigger picture.

—Ross Simonini

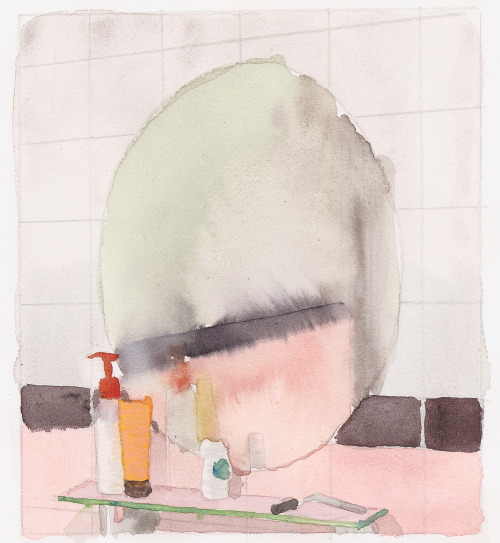

THE BELIEVER: How did the mirror painting series begin?

ROGER WHITE: In 2009 I was with my wife in Taipei. She was there on a grant during the summer. It was very, very hot and humid, and I didn’t speak any Chinese, and so I spent a lot of time in the apartment, a tiny little apartment near Daan Park. I would go downstairs to the 7-Eleven to get those little triangular seaweed-and-rice snacks, and come back up and just make watercolors. The bathroom had terrible pink and purple tiles, and a little oval mirror, which was always fogged due to the constant humidity. I made a watercolor of it, and then every nine months or a year since then, I’ve thought, “Oh I should do something with that.”

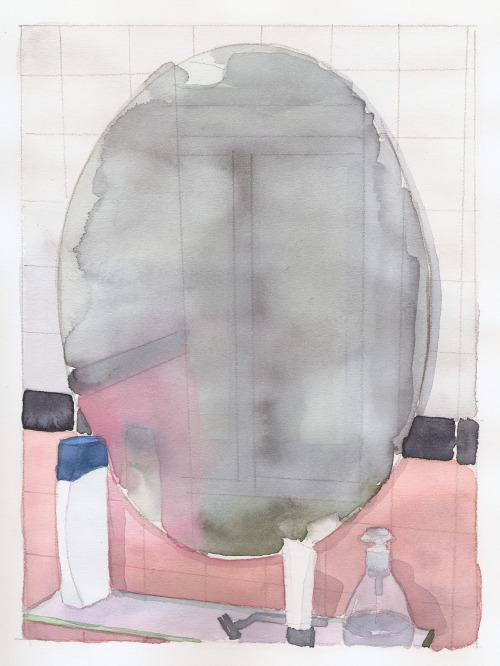

So last year I took up the project again with a little more rigor. I set about trying to reconstruct that image, away from the actual site—since I wasn’t likely to get back to Taipei and rent that same apartment again. I started by making a painting from the watercolor, which didn’t work out at all. There was too little information. Then I started re-drawing it, asking myself, “How far away was I from the wall? What were the colors like? How high off the ground was the shelf?” Doing that, you realize how little you actually remember about something. Especially after you’ve committed it to some other form, a drawing or a photograph.

BLVR: The art makes you forget.

RW: Yeah. So first I tried to re-imagine the situation, working purely from memory. Next, I set up a shelf and some objects and gridded off the wall…

BLVR: You recreated it?

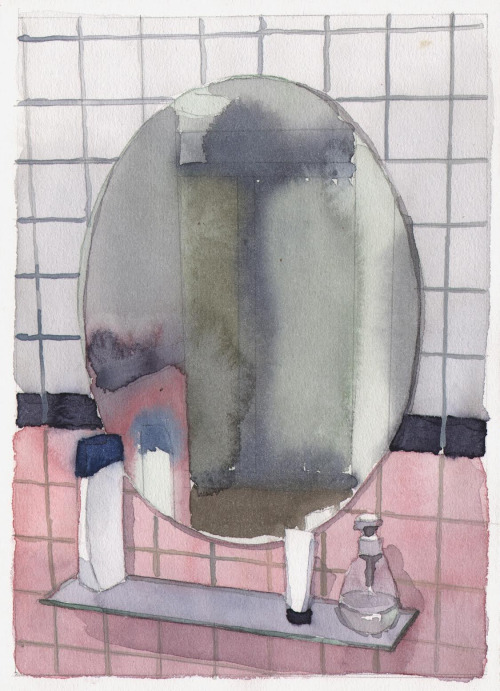

RW: Yeah. Eventually. I bought a mirror, built a wall, tiled it, installed a glass shelf, and did drawings from that. I did that twice, actually, because I moved studios. I got very fussy about it. Adobe Illustrator was involved. A humidifier was involved, to fog up the mirror in order to observe it.

BLVR: Do you consider these to be studies?

RW: Yes and no. There are so many variations now, and when I do make an oil painting it’ll probably be a totally different process anyway. Besides, I usually I feel like most of them are still very unsatisfying.

BLVR: What is it that you don’t think is successful?

RW: Well it’s just—I mean it’s, like, minute. Angles, the color being exactly keyed in. Watercolor is sort of chancy. If you get one thing right, you know, five other things are different. The other question is, “Well how much like a fog mirror is it supposed to look?” I don’t want to work from photographs on this one. I mean, I look at pictures of foggy mirrors all the time now, but there’s no one image that corresponds to each watercolor, and I feel like that’s somehow important. I’m neither sitting in front of the scene or referring to an image. It’s this painful, reconstructive process.

BLVR: The painful part—is that important?

RW: It probably is, it probably is. I want to say it’s not, but it totally is.

BLVR: Why is it important that it’s not all coming from a single image?

RW: It doesn’t allow the things that I want to happen to happen. The full mental process is about trying to see it, get it back, or trying to… have you read Remainder by Tom McCarthy?

BLVR: Oh, yes, I immediately thought of that when I saw this.

RW: The protagonist in the novel, who is suffering the after-effects of a severe head injury, is at a party in an apartment and visits the bathroom, where he imagines a crack running down a wall that isn’t there. Ultimately, he builds an entire new building around the idea of this imagined, cracked bathroom wall. I really dug the way the book reflected on some of the concerns of visual art.

BLVR: That book is one of the few recent novels that hits upon some of the thinking in contemporary art. The whole thing felt sort of like an installation.

RW: Yeah, it was a gratifying book in that way.

BLVR: Did you begin with watercolors?

RW: I started making watercolors as a way to think about making oil paintings, five or six years ago. It was a quick visualizing tool to work on ideas for the paintings, and it just evolved into its own thing. A lot of my work is about translating back and forth between different versions of things, different media or scales.

BLVR: It makes me think a little of Carroll Dunham, how he’ll just, he’ll make one image over and over and over and over again, hundreds of them, just working out those very tiny nuances.

RW: Yeah. He’s a good example of that because on first acquaintance with one of those images, you wouldn’t imagine that he had rehearsed it so many times.

BLVR: By doing something repeatedly you don’t want the image to end up looking rote. You want it to feel fresh each time.

RW: Yeah. Watercolor is great for that because you can’t control it very well and it’s not gonna behave the same way twice, so you’re never—it’s hard to get to rote, in fact.

BLVR: You said there’s a fine line between making an image of a foggy mirror and a pure abstraction. Why push it towards the foggy mirror? Why does it matter that you’re capturing reality?

RW: [Blows air through his lips so that they flap and make noise]. Um, yeah, that’s a deep one.

BLVR: If it’s too deep…

RW: No, no, it’s great.

BLVR: Well, I think for you especially because you dance between abstraction and representation.

RW: Well, I feel that even when I’m working more or less abstractly it’s still a picture. It’s still engaged in the question, “What does it mean to represent some thing in the world in some way?” And without that question I’m totally lost as an artist. I started my training as an artist through observational painting and drawing, and that seems, for me, right now, a more complicated problem than that of making abstract paintings. I can’t personally get enough intellectual perspective on what an abstract painting is in order to think of it only in those terms.

BLVR: Do you think anybody does, really?

RW: Well, you have to be engaged with a more polemical discussion about what painting is in order to really make abstract paintings now. Or a spiritual one. And I’m not doing either. I’m much more interested in what things look like.

BLVR: Right, more image-based. I can imagine why you’d want to make a big painting of these because it would reference the experience of looking at a mirror. Getting swallowed by it. But with a small piece, it remains an image.

RW: Contained. There’s something disarming about small work. Our sophisticated skepticism isn’t engaged quite so much.

BLVR: Do you think these watercolors are all referring back to that single moment?

RW: Not anymore. It just drifts. At one point I flipped the whole thing around, did some imaginary redecorating… that’s the interesting thing about working in a series or over long periods of time. It just goes other places. A lot of the subject matter I deal with has a kind of “it could be anything” quality. With this one, it’s a fairly banal moment that we’ve all experienced in one way or another. It wasn’t like I stood in front of the foggy mirror and had a revelation about mortality. Afterwards, I’ve had any number of thoughts about representation and abstraction, optics, portraiture—George W. Bush’s bathroom self-portraits, in fact, to be specific—but really I happened to be there at that moment and thought it might make an interesting image. It was just paintable. An inherently paintable moment.