On Women in The Tale of Genji By Becca Rothfeld

Western literature has much to offer in the way of incorrigible womanizing. Casanova and Don Juan, names by now virtually synonymous with elaborate feats of seduction, summon up stylized images of intrigue: letters delivered by conspiratorial ladies-in-waiting, wildly beating hearts, and clandestine meetings on the grounds of Gothic manors. It is no accident that consummation rarely figures into our retellings of these narratives, which emphasize a glamorous dance of advance and retreat, pressure and resistance. The allure of the seducer is bound up with the deferral of his purported aim—with the prolonged tensions and delayed gratifications that transform his beloved’s most banal gestures into dazzling enticements. Don Juan and his ilk appeal to a fantasy of gratification without accountability. The women they seduce are always pictured on the verge of surrender, but as soon as one of them actually submits she begins to fade out of sight.

But these amorous icons, prolific as they are, can hardly compete with Genji, a legendary lover who hails from an altogether different tradition. The son of a powerful emperor, the so-called Radiant Prince skillfully navigates the landscape of a fictional Japanese court, initiating near countless trysts along the way. The most significant of his many paramours is Murasaki, whom he raises as a daughter and weds (read: deflowers) when she is still prepubescent. Genji’s insensitivity to the women he compromises rivals Don Juan’s—but his exploits were dreamt up by a woman, an eleventh-century Japanese courtier nicknamed Murasaki Shikibu, after her best loved character (her real name is unknown). It is perhaps for this reason that the liaisons in The Tale of Genji do not end at the moment of female capitulation. Instead, they continue, often disastrously, for months or years, muddied along the way by entanglements and recriminations. The book—if never the Japanese aristocracy itself—holds callous male lovers at least implicitly accountable.

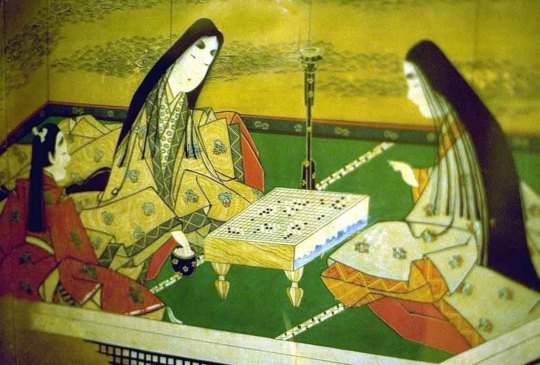

Written at the turn of the eleventh century, The Tale of Genji is arguably the world’s first novel. Though it appeared long before Western literary scholars had the familiar concept of a “novel” at their disposal, it spans over a thousand pages and is undeniably novelistic in scope. The work purports to take place during the reign of a fictive emperor, but the milieu it depicts closely resembles the one in which Lady Murasaki lived and worked. During the Heian period (794-1185), male nobles and royals were bigamous: they had multiple “consorts,” each of whom presided over a separate court. This arrangement fostered competition between wives, who were forced to jockey for their husband’s time and affection. Consorts found themselves at pains not only to forge strong interpersonal ties with their husbands but also to cultivate refined courtly environments, engaging female musicians, artists, and women of letters to tempt their husbands with the promise of rich artistic experiences. Murasaki Shikibu was one such accouterment, employed as a resident writer and wit in the court of Empress Shoshi, the second consort of the Emperor Ichijo. (Sei Shonagon, author of the renowned Pillow Book, was associated with the rival court of Empress Teishi, another of Emperor Ichijo’s consorts.)

Though there was a place for educated women in Heian society, their literary province was oddly circumscribed. They found themselves with something of a monopoly on literary language, a happy byproduct of their exclusion from learned and political discourses: discouraged from learning the Chinese script (kanji) favored by male scholars and statesman, women made recourse to hiragana, or “woman’s hand” (onna-de), a phonetic rather than idiographic alphabet. (Modern-day Japanese makes use of three alphabets, kanji for lengthy expressions, katakana for foreign phrases or headlines, and hiragana for grammatical inflection.) Using onna-de, women were able to trade in puns and ambiguities—while men, constrained by kanji’s more ostensive significatory structure, were limited to more explicit assertions in their written work.

Because literature played so central a role in Heian courtship rituals, it promised to serve as a particularly potent site of female resistance: it would seem that the Heian woman’s mastery of hiragana gave her an advantage at least in the domain of arts and letters, where allusions and subtleties reigned supreme. In The Tale of Genji, where the sex act is peculiarly desexualized, texts often come to stand in for bodies. Trysts are arranged via the exchange of poetic love letters, and face-to-face meetings are few and far between. Physical attraction is something of an afterthought, in large part because it is so difficult for men and women to catch so much as a glimpse of one another before an actual rendezvous. In Heian Japan, noblewomen were not only stripped of physically individualizing features—they wore cumbersome garments that disguised the curves of their bodies, plastered their faces with white make-up, blackened their teeth, and shaved off their natural eyebrows—but they were obliged to converse with male callers from behind modest silk screens.

Deprived of physical contact with his love interests, Genji gauges female beauty with reference to the elegance of a woman’s calligraphy, the tastefulness of her stationary, and the eloquence of her verse. During a long conversation about the nature of female perfection in the “Hahakigi” chapter, one of Genji’s friends proclaims that an ideal woman “would be well versed in composition, but her choice of words would be modest and her brushstrokes light and delicate…” He assesses her merits as a text, not a body.

Eroticism, then, is a question of conforming as expertly as possible to the set of elaborate norms and restrictions governing the composition of a love letter. (Sei Shonagon’s Pillow Book is in part a set of guidelines for an aspiring poet, featuring long catalogues of imagery that explain which metaphors are appropriate for which situations, which mountain range or river to invoke in which context, and so on.) Letters had to be perfumed correctly and penned on appropriate stationary, and the poems they contained had to display an artful grasp of the conventions of the tanka poem, which consisted of a five-syllable line followed by a seven-syllable line, another five-syllable line, and two seven-syllable lines.

The textual focus that prevails in Genji was not out of place in Heian Japan, where men seemed to regard their amorous entanglements as mystical rather than physical exchanges, and often attributed their feelings of romantic attraction to karmic bonds established in former lives. The spiritual aspects of a romantic connection were not infrequently privileged over material ones: according to Japanese lore, the spirits of lovers often vacated their bodies as they slept so that couples could meet in their dreams. Such encounters were sometimes considered preferable to “real” meetings, as the 647th poem in the tenth-century Kokin Wakashu poetry anthology so beautifully clarifies: “the reality of our meeting in the pitch black darkness was in no way superior to seeing you clearly in my vivid dream,” it reads.

But the supremacy of signs is not without its complications. The nominal literary dominance enjoyed by female writers in Heian Japan shifted the perimeters of a stifling system only slightly, and the efforts of figures like Murasaki Shikibu were directed, in the end, towards attracting husbands in an inequitable marital economy. Because male attention was a scant resource, the consorts who vied for it—and, by extension, the writers and artists in their service—were systematically devalued. It might seem, at least on the face of it, that the resulting literary products, relegated to the role of currency in a structurally rigged market, suffered the same fate. Their authors, so often reduced to the quality of their textual output, risked exposing themselves to the interpretive whims of an uncharitable male readership.

In a world where romance is a matter of written reverie, arousal is a function of fantasy, not touch. The most alluring women are the most unprotesting vehicles for the fulfillment of male longings, and throughout The Tale of Genji the ideal woman is presented as a passive and unassuming canvas (or text) onto which male desires can be projected with ease. The less she asserts her own character, the less she conflicts with the role that men have imagined for her. Docility is at a premium, a notion that manifests itself most radically when a woman dies and thus eliminates the possibility of contradicting her suitor’s wishes: to Genji’s father, Genji’s mother looks “alluringly vulnerable as she lay there in a semiconscious state” on her deathbed, and the corpse of one of Genji’s deceased mistresses, The Lady of the Evening Faces, fills him with “a painful sense of yearning.” Because dead lovers, submissive as they may be, are lamentably off-limits, Genji clambers to find “a completely childlike, compliant woman” whom he “can mold into an acceptable and flawless wife.”

But in the flesh, and often even in verse, the women of Genji’s court tend to contradict male idealizations, Pygmalion-esque attempts at “molding” notwithstanding. As Genji’s friend To no Chujo notes in the Hahakigi chapter, “I’ve come across many who have passable skills in the arts, who can write flowing characters that create an impression of superficial elegance, who show a kind of facile understanding of how to respond in verse on certain occasions. Yet even when one chooses a woman on the basis of such accomplishments, she almost always fails to live up to the expectations created by her talents and disappoints in the end.” Here the familiar trope that drove Casanova and Don Juan rears its ugly, noncommittal head: a man must defer the fulfillment of his fantasy if he is to effectively sustain it. With the ideal woman, Genji’s friend remarks, “you are forced to wait, feeling unbearably impatient until that moment when you can get close enough to her to make your advance and exchange a few words.” Preamble is built into the rites of love from the start—and indeed, the entire apparatus of Heian courtship is designed to shift the focus of an affair from consummation to foreplay.

But, happily, the close attention that Heian nobles afforded written declarations cut both ways, and any deviation from standard literary procedure reverberated powerfully. Heian courtiers possessed a heightened sensitivity to literary subtlety that enabled Lady Murasaki to infuse The Tale of Genji, ostensibly written in praise of the Radiant Prince, with a litany of subversive complaints. Beneath the measured propriety of her prose, we detect the tenor of her own discordant voice.

In one memorable scene, one of Genji’s wives, the so-called Aoi Lady, expresses her rage via an unconventional outlet: her difficult childbirth and subsequent death give voice and form to a host of long-repressed complaints about Genji, who has been neglecting her in favor of his other wives. Her nausea, writhing, and bouts of “shouting out and weeping” are visible expressions of her otherwise invisible suffering. Fittingly, when she survives childbirth and returns briefly to her former good health, she finds it difficult to speak: the after-effects of her illness afflict her throat, inducing a sensation of choking. If female illness amounted to a rare occasion for unfettered self-expression, then “good health” amounted to business as usual—the ongoing silencing of female concerns. Murasaki makes use of similar tactics, giving vent to her dissatisfaction only indirectly. Her complaints masquerade as an unrelated event—a novel.

Sometimes, Lady Murasaki explicitly inserts her own commentary into the narrative, as when she witheringly remarks that Genji’s infidelities are an indication of “the shallowness of his fickle heart.” Sometimes, she protests implicitly, describing a scene or state of affairs that is obviously at odds with a male character’s assessment of it, as when one man, irritated by a devoted wife’s jealousy, “intentionally treated her with wretched callousness” until she became so upset that she died.

But most of all, Lady Murasaki’s very existence is at odds with the values promoted by Genji and his friends, and, more broadly, the men of the Heian court. Murasaki, one of the few noblewomen at the time to have studied the Chinese classics, must have been thinking of herself in the section where one of Genji’s confidants recounts his affair with a woman so intelligent and well-educated as to seem “mannish”—a woman whom he punishes for making him appear stupid and unlearned in comparison. “For a man like me who has no intellectual talents to rely on a woman I was intimate with and have her witness my pathetic performances… well, it as too shameful,” he laments. A friend replies, “a woman who acquires knowledge of Chinese and has read the Three Histories or the Five Classics lacks all feminine charm… when you see such a woman you’re filled with chagrin, wondering why she couldn’t be a bit more soft-spoken and ladylike.” He goes on to complain about how difficult it is to reply with suitable wit to the ingenious poetry composed by such women, who make men look “ridiculous.” And yet the very men who resented Murasaki’s facility with words remained captivated by her narrative—one that they undoubtedly could not have even attempted to write without looking, as they unknowingly acknowledge, “pathetic.” Unlike Don Juan and Cassonova’s diminutive conquests, Murasaki refuses to fade out of Genji’s romantic narrative, even so many centuries later.