An Interview with Ottessa Moshfegh

I first read Ottessa Moshfegh’s fiction in NOON. After that, I found her other stories in The Paris Review, where she was awarded the Plimpton Prize in 2013. In 2014, Rivka Galchen selected her novella, McGlue, as the winner of the Fence Modern Prize in Prose. McGlue was shortlisted for The Believer Book Award. Moshfegh has won a Pushcart Prize, an NEA award, and was a Stegner Fellow at Stanford. Her current novel, Eileen, is just out from Penguin Press and deals with a young woman in 1964 New England who finds herself befriended by a woman who lures her into a dark and harrowing crime. We chatted recently about Eileen and other things.

—Brandon Hobson

BRANDON HOBSON: One of the things that fascinated me about Eileen is that she seems unsure of her sense of affection. Early in the book she tells us that she bit a boy’s throat and didn’t care that it drew blood—a fantastic description and confession, by the way—yet she seems shy and unsure about admitting her attraction to Rebecca.

OM: Yes. She bit a boy’s throat because he was trying to get his hand up her skirt. Her affection for Rebecca is complicated.

BH: Their complicated relationship is what really drives the book for me. The situation with Eileen’s alcoholic and abusive father is sad. At one point, she says she sees herself driving off a cliff. Did you want her to be emotionally immature or suicidal?

OM: She’s not suicidal. I think that’s her saving grace—her desire to live. As for being emotionally immature, she is only twenty-four years old. She’s had to cope with a lot of trauma in her life. In some ways, she’s weathered. In others, she’s experiencing some arrested development; she never learned to take care of herself.

BH: I’m fascinated with how her character copes with this trauma. In this way the book is disturbing on a level that reminds me why I love good art: it arouses, makes one uncomfortable. Is that what you try to do with your writing?

OM: I love art because I feel that it’s evidence of the great shared universal power. Some of us can access it in ways that are easier to express. I like art that feels real, that cuts the bullshit. So I didn’t want to write a book that pretended that everything was fine. Eileen’s story isn’t some reductive nonsense about how she had a crush on a boy, and then realized that she had to learn to love herself, or something. I really wanted the book to pull the curtain back on the ugliness people live in every day.

BH: You mentioned in another interview that Lee Polk’s character and situation inspired this book and Eileen grew out of that. Who or what inspires you?

OM: Yeah, Lee Polk’s situation really moved me. What’s inspiring me the most right now… injustice. My own growth as a member of the human race, in terms of the veils being lifted, seeing more of the beauty and also the horror. A sense of my own purpose in this life. Love…

BH: What about a sense of spirit?

OM: Yes. My spirit is very happy as the veils are lifted, happier and happier.

BH: I’m happy to hear that.

OM: Too bad the human psyche is so vulnerable to fear. I just get angrier and angrier.

BH: I get afraid late at night. My house makes noises sometimes. It’s an old house with lots of spirits. It once belonged to a Madam who I’m told was really nice. Is there a place you like to go to write? Or a place that inspires you?

OM: I think a lot about the woods of Maine, where my family has an old camp on a lake. I don’t write a lot when I go there, but imagining it helps me set aside the tedium and horseshit of daily life when I want to write from a deeper place. I get afraid late at night there, too. I’ve seen some things. The loons on the lake protect me.

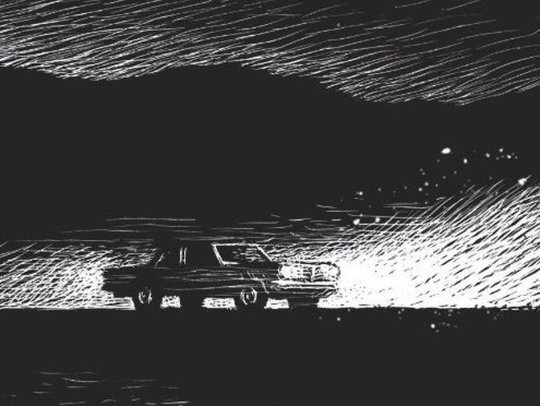

BH: It’s the inspiration for your story “A Dark and Winding Road” from The Paris Review, right?

OM: Yes.

BH: Which is so, so good.

OM: I love that story. I love the brother in that story. He never appears, but I felt very close to him.

BH: Eileen says she loves men for their weakness, which is sadness. Most of the men in the book seem sad and angry.

OM: I’d be sad and angry if I were them. The warden at the juvenile prison where Eileen works, however, seems perfectly pleased.

BH: Right, yeah, the warden isn’t sad or angry.

OM: Yeah, that fucker.

BH: The two men at the bar seem pathetic.

OM: How so?

BH: The way they harass Eileen and Rebecca.

OM: I think everyone has experienced this in a bar. Men being pathetic in their desire to get laid. Women too, of course!

BH: A bar is always a place for people to feel like they can harass others and get away with it. Do you like to make the reader feel uncomfortable?

OM: Well, yes. But that’s not what my work is about. It’s not necessarily about “feeling uncomfortable.”

BH: Can you explain?

OM: If you look at the horror genre, that work is all about making people uncomfortable by stimulating our fear of death. The kind of discomfort I’m interested in is the hangover you feel when you wake up out of the glossy mirage in which everything is fine the way it is. When I’m stuck in that mirage myself, I take no responsibility for the welfare of others. I am trapped in my homeostasis, and therefore I want everyone to stay trapped with me. Some people think of it as the brainwashing of Big Brother. I see it more as being captive to your own fear.

In Eileen, I think the discomfort a reader might feel is seeing the truth in what we let happen. Abused children are being locked up and tortured while I type this. So reading and thinking about that horror makes me uncomfortable. Think about every time you’ve seen someone being objectified, abused, enslaved. We see it constantly on the TV, in magazines, on the Internet. We’ve become numb, so we do nothing. The accumulation of passivity might make reading about that exploitation uncomfortable. And sometimes when I’m writing, I think of it like this: “People seem to like garbage, so here is what garbage smells like…” It’s uncomfortable to look in the mirror.