Kaya Genç on Artist Şener Özmen’s “There Is a Way Out”

In 2009, the Turkish government announced its Kurdish initiative, an attempt to solve the country’s century long conflict with Kurdish citizens. In Ankara, the mood in Parliament resembled the 1920s, and politicians voiced their refusal “to sacrifice the basic principles based on pluralism, freedom, and democracy eighty-nine years ago”. This, we hoped, would be the beginning of a new era of democratization.

Starting in February 2013, peace talks started to come under scrutiny; peacemakers who contributed to the process were criticized by nationalists on both sides. The peace process somehow managed to continue under great duress until July this year. In the seven weeks that followed, more than 202 people died (one hundred and seven security officials, fifty-eight PKK insurgents, and thirty-seven civilians, according to the International Crisis Group). For those who had watched the Kurdish initiative from the beginning, the new upsurge in violence meant that the message the initiative had carried—that there was a way out of the bloody conflict that has been stifling this country’s progress and peace for almost a century—was now torn to pieces and would no longer be heard by the public.

“There Is a Way Out”, the title of a new exhibition by Diyarbakır-based contemporary artist Şener Özmen, opened two weeks ago in Istanbul’s PİLOT gallery. Known both as a novelist and artist, Özmen’s life has been strongly determined by the conflict. At the entrance of PİLOT gallery’s ground floor you can read Özmen’s letter, dated October 2014, which he wrote after he could not participate in an artistic panel discussion at the Istanbul Biennial alongside artist Hito Steyerl and curator Fulya Erdemci.

“As you also know,” Özmen writes in the letter, “’Kobane Protests’ that have caught on like wildfire primarily in Diyarbakır and the neighboring cities and districts prevented me from attending the talk. I had a 7:15pm flight to Istanbul and wanted to spend more time with Robin.” Özmen’s son Robin is seven-years-old and, arguably, the star of the exhibition. In Özmen’s letter we learn about how Robin talked with his father about the reasons why he can’t travel to Istanbul to attend the Biennial. Then they take a walk in the city.

“I held Robin’s hand and took him to the new mall near our home, to the Dinosaurs Exhibition. I took a couple of photographs with my cell phone. We hung out around the escalators, we wandered around the floors. There was not a soul around… It took an hour or so. We went back home, reluctantly.”

For his PİLOT exhibition Özmen has turned this very personal and touching letter into an “A4 size light beam”. “This text is part of my literary oeuvre,” Özmen told me last week. “Illuminated, the letter hangs on the wall like an ancient tablet, in one corner of the dimly lit gallery space. The work takes its power from tablets found in ancient times, from the sacredness of the written word.” According to Özmen, the written word shows a way out of the catastrophe. “This is what art does,” Özmen told me. “It searches, explores, and communicates. We wanted the exhibition to open with the artist’s written word.”

In another corner of the gallery, there is a tripod trapped in a concrete pedestal, its legs no longer able to be move. The sculpture, Tripod, seems scary in its immobile, unmoveable quality. But it’s also funny: the tripod has been stripped of its function of balancing a camera, and now can’t do anything.

According to the exhibition, Tripod “takes us back to the years when Özmen did not and could not use a tripod.” And Özmen now describes those years as a nightmare—even the existence of the tripod had seemed threatening. “I had carried the tripod with me everywhere, but there was no way to use it. Instead, I had to find a cameraman to balance the camera as if he were a tripod. The horizon line was always crooked. I had become an artist who lost his horizon line.” The tripod posed a theoretical problem for Özmen’s artistic career. He couldn’t feel safe outdoors because of how visible the equipment made him.

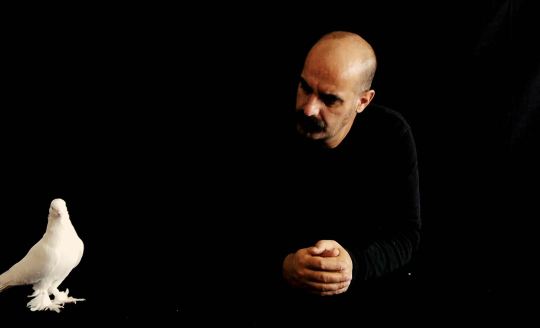

Özmen’s attitude has changed. For his film, “How to Tell Peace to a Living Dove?“, Özmen worked indoors. “This time there was no threat from outside. I felt comfortable,” he told me.

The piece begins with a text read by Özmen’s son Robin. “Frankly, dear little dove, you and I should have met before our unrecognized lives turned into hell, not now!” Özmen and the dove are shown from different angles, lit inside a depthless and pitch black room. “Good things could happen even here, dear white dove, and they do occasionally happen,” Robin continues. “How can I tell you about something I don’t know, haven’t seen or experienced? I will set you free dear white, desperate dove. Not politically. Because we are unable talk about peace in a land like this, full of doves.”

Özmen says the only way out of violence is through distancing ourselves from hate speech. Describing himself as a nihilistic artist, Özmen finds it ironic that he’s become the one to say, “There is a way out.”

“Robin was the first to use the word peace,” Özmen told me when I asked about working with his son. “At the beginning he sat down to write his feelings. I didn’t know that this would turn into a video installation. I realized: children deserve peace the most. As adults we were somehow were usurping their chance of achieving it. It was painful to realize.” Robin had refused to read the text at first but eventually agreed. He shot the video twice, and Robin sat next to him as he edited it. “Robin listened to his voice, watched the dove and his father together. His only concern was for the fate of the dove.”

After shooting the video, Robin watched his father release the dove—a poetic and political gesture. More than anything, Özmen and the show seem to say that, despite everything we have been seeing in the past month, there is still a way out for this country.