A Remembrance of Robert Seydel By Matthew Erickson

Discussed: Vacation Reading, A Certain Eccentric Photography Professor, Monkish Time-Carving, Borgesian Syllabi, Tobacco Fumes, Emily Dickinson’s Family Homestead, An Actual Aunt, A Watershed Moment, An Exit from the Self, Serial Invention, A Scarlet Star

I first met the artist and poet Robert Seydel halfway through my second year at Hampshire College, after sending him a cold-call email asking if he would oversee an independent study on the literary group the Oulipo. Over that winter break, I had devoured my girlfriend’s tattered copy of Italo Calvino’s If On a Winter’s Night a Traveler, and I wanted to spend a full semester taking a deeper dive into its tradition of intricate, constraint-based literature. When I asked around to see who might be able to take this project on, the name of a certain eccentric photography professor—one who chain-smoked, slept little, worked feverishly on his art, and nurtured his students’ peculiar obsessions as though they were his own—kept coming up.

Although photography was Robert’s supposed métier (he studied the medium in graduate school, and was for many years a curator at Boston University’s Photographic Resource Center before turning to teaching), his enthusiasms were deeply and genuinely hybrid; fiction and poetry influenced him as much as anything in the visual arts did. By the time I began to work under him, in the early aughts, Robert’s photographic practice had shifted toward something significantly more complex than his early work: he had become a maker of meticulously layered works on paper that incorporated all manner of found imagery and flattened street detritus, delicate small assemblages in antique cigar boxes, and an interrelated stream of written texts, all created using a common language of invented, cipher-like characters.

Robert took me on for the Oulipo study, despite his overextended schedule that semester, purely out of his own deep fondness for the more experimental strains of world literature. I then spent the next two years working with him in his idiosyncratic studio-art courses, and eventually had him on my final-year thesis committee. I remember Robert telling me, as I’m sure he often told other students who worked closely with him, that “our culture doesn’t support what we do, so we need to carve out time for our real work.” For Robert, that time-carving was a strict daily regimen, almost monkish in its commitment to art. His creative practice was a daily ritual. Every day, he would wake up early, hours before his paid workday began, to read intensely, smoke cigarettes, and drink coffee. In the evenings, coming home from teaching and meetings and class critiques and more meetings—and if he didn’t have any social obligations—he would unplug the phone, make another pot of coffee, and get back to work, which, for him, was more like play than actual labor: “work as play,” as he liked to put it. He maintained this schedule of solitary rigor for many years.

In a number of ways, Robert was a perfect match for Hampshire, which first opened as an experiment in higher education in 1970 and today retains many of the radical pedagogical approaches from that founding era. Nestled into a slowly undulating landscape of farmland and apple orchards near the outer border of Amherst, Massachusetts, the college can still be utopian for students whose academic interests lie across traditional departmental boundaries. A student’s final year is spent producing a single work in his or her chosen discipline or combination of disciplines, alongside a small committee of professors. As a deep admirer of the storied Black Mountain College—as well as of the artists and poets involved with that visionary moment in mid-century arts education, such as John Cage, Robert Creeley, Charles Olson, Robert Duncan, Ray Johnson, and others—Robert must have imagined Hampshire operating within a similar tradition, a kind of semi-rural laboratory where faculty and students could experiment in tandem.

When Robert sat on my own thesis committee, I met with him weekly and, in the warmer months, we would stand outside while he smoked an endless series of cigarettes and talked about film, gallery shows, poets, novels, museum catalogs, sound art, Townes Van Zandt, small presses, anthropology, art brut, and other topics barely even tangentially related to my own project. His exhaustive, Borgesian syllabi capture his spirit perfectly. Covering his outlines for several ambitious photography workshops (like “Still Photography II: Art, Personae, and the Performance of Selves”) and a few interdisciplinary courses (“The Walking Arts” and “The Collector: Theory and Practice,” a popular class that was co-taught with art historian Sura Levine), each syllabus is near twenty pages long and swollen with quotes, images, exercise ideas, and exhaustive bibliographies. Each lengthy inventory of suggested books is preceded by a category subject, which often forks off into several subcategories, each with their own reading lists. One bibliography, for an introductory studio art class titled “Collage: History and Practice,” was organized in this labyrinthine structure:

Collage: 1) General, 2) Cubism (Mostly Literary), 3) Italian Futurism, 4) Russian Futurism (Cubo-Futurism), 5) Dadaism, 5a) General, 5b) New York Dada, 5c) Marcel Duchamp, 5d) Zurich Berlin Cologne and Hannover, 5e) Paris Dada, 6) Surrealism, 6a) Preliminary, 6b (Writings), 6c) Secondary (Histories and Visual Anthologies), 6d) Other Surrealisms, 6e) Jean Dubuffet and Art Brut, 6f) Art Brut (Selected Individual Artists), 6g) Joseph Cornell, 7) Bauhaus (Highly Select), 8) Cobra and Situationist International (Highly Select), 9) OuLiPo (Workshop for Potential Literature), 10) Fluxus, 10a) Dieter Roth, 11) John Cage, 12) Jiri Kolar, 13) Ray Johnson, 14) American and British Pop, 15) California and Beat, 16) New York School, 17) A Few Others, 18) Literature (Highly Selected).

Almost the entirety of twentieth-century avant-garde art is crammed into this one lower-level course syllabus, which brims with contagious excitement.

During a meeting in his office, Robert once told me that reading, not art-making, was his primary activity. “I’m basically a reader. That’s just what I do,” he said. Though this was an understatement for an artist who made such vast quantities of work, his reading life was truly central to his creative life. Lisa Pearson, publisher of the art-book press Siglio, writes that Robert’s “library was a marvel, a work of art itself. His shelves had rows of books two deep—pull out a book and there was another behind it, and there were stacks of books everywhere—on top of the fridge, next to the stove, in the closet, on every available surface. In his notebooks, he made lists of the books he was reading—twenty, thirty, forty at a time.”

He was a serious bibliophile, yet books for Robert were more than just collectible objects or containers of ideas that could find their way into his visual work. His daily practice of morning reading functioned on levels deeper than just influence; he structured his work in the mode of a fiction writer, thinking as much about narrative echoes and ways to inhabit characters as about pure imagery and aesthetics.

I once had the opportunity to look through Robert’s professional portfolio during a routine rehiring process. Along with his requisite C.V., letters from colleagues, and course syllabi, were several pages of color slides documenting fragments from his then-recent collage journals and notebooks, in which he was working almost exclusively. He coined these “knotbooks,” perhaps to allow space for the intertwined visual-textual narratives that slipped back and forth between writing and collage. The slides showed hundreds of images and revealed a frenzy of creative activity from just the previous year or so—yet even that mass of work seemed edited down, as though those hundreds of discrete yet interrelated works were in fact only a small portion of what was contained in the greater shelf of finished knotbooks sitting in his studio. At that point, the images documented on the slides had only been seen by that one rehiring committee and a few close friends.

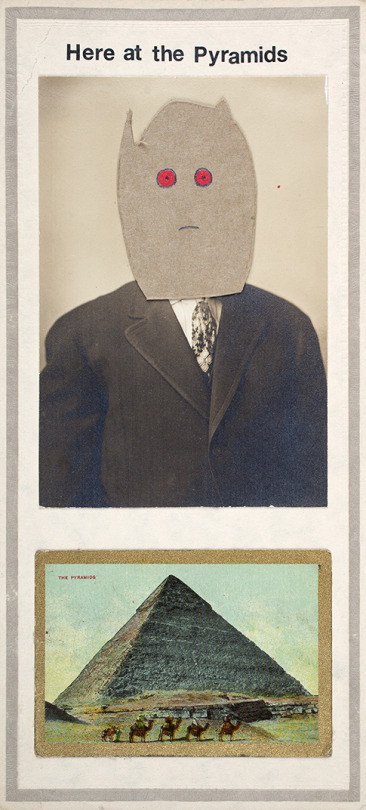

“Untitled Journal Page [“I was beautiful as a girl”]” by Robert Seydel, n.d. © the Estate of Robert Seydel. From A Picture Is Always a Book: Further Writings from Book of Ruth (Siglio and Smith College Libraries, 2014).

***

Once I finished my undergraduate thesis, a collection of essays and visuals on the history of encyclopedias that doubled as an artists’ book, Robert suggested that I drop off a copy at either his house or his office on campus. When he emailed me his address, I learned that he lived and worked on the street parallel to the one where my girlfriend and I had been renting an apartment, a couple of blocks down the road from Emily Dickinson’s family homestead in Amherst, but unsure of how to make the transition from a mentor-student relationship, I ended up leaving the book in his campus mailbox.

I maintained only sporadic contact with Robert once I graduated. A year or so after I moved away, though, in 2007, he sent me the catalog for his first solo exhibition of collages, at the CUE Foundation in New York, with a sticky note on the inside cover in his signature truncated notational style: “Matthew—Hope y’re well. Cheers! Robert.” (His handwritten notes and comments on student work echoed the language that poet Charles Olson used in his correspondence with Robert Creeley, replacing “sd” for said, “shld” for should, “yr” for your. This was partly an affectation for Robert, but it also connected these incidental scribblings to the prose style coursing throughout his work, as though the daytime writing to students was a rehearsal space for the nighttime production of his own text-oriented work.)

By the time of the CUE show, Robert was in his early forties—rather late, by the youthful standards of the contemporary art world, for a gallery debut. The year before, he had participated in a group show called “Five Contemporary Visual Poets” at a small Seattle gallery, and years earlier had been awarded a regional fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts for his serial photography project “A Short History of Portraiture,” but he had long been guarded about showing his work in a wider public realm. Though he showed his art to friends and sometimes to students, he was protective of his process and decidedly non-careerist in his aspirations. That thin catalog seemed to indicate to me that he would finally get some acknowledgment after laboring away for years in this self-imposed seclusion.

A few years later, I was working sporadically as a substitute teacher in the San Francisco public schools, Robert’s dictum about carving out time for my own projects always quietly ringing in the back of my mind. I traveled through every foggy pocket of the city and somehow scraped together a living as a kind of journeyman educator, with plenty of surplus time to play with and to aimlessly squander. Most of those work days have blurred together in my memory—cleaning up crushed Goldfish crackers from one kindergarten carpet or another, intercepting lewd notes by the dozen in one of many middle schools—but a particular mild winter afternoon stands out in slightly sharper relief.

One late January day in 2011, I had wandered into the magazine section of Green Apple Books after a day at a nearby elementary school. I flipped through the newest issue of BOMB Magazine and was thrilled to see an excerpt of a handful of page spreads from a then-forthcoming book of Robert’s ongoing serial work, which he had mentioned in passing during those earlier undergrad thesis conversations. At that moment, standing before the shelves in the bookstore, it seemed like he was again on the brink of finding some kind of audience after years of hermetic dedication. I told myself that I’d email him the next day to congratulate him on his first book, a long time in the making.

The following morning, the news came that Robert had a heart attack in his campus office that day while preparing for the upcoming semester. He was fifty years old.

***

The Los Angeles–based Siglio Press has singlehandedly elevated Robert’s work from the special kind of obscurity that is reserved for reclusive and decidedly non-careerist artists. Lisa Pearson, the founder and editor of Siglio, has said that she started the press partly with the intent of publishing Robert, who had been a close friend for many years. Though he was a rather solitary figure in life, his few close friends—particularly Pearson’s husband, the artist Richard Kraft, who had known Robert since college, and the poet Peter Gizzi, who first met Robert in high school—have been vocal champions for his work in the years since his death.

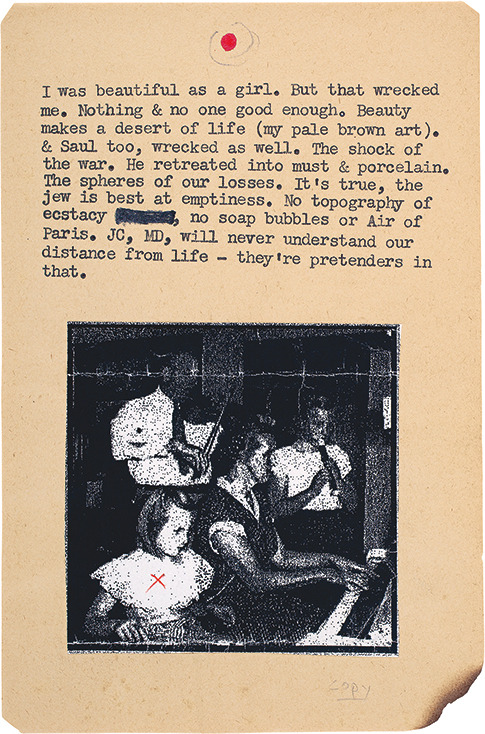

In 2011, Siglio published Book of Ruth, which was in its production stages just before Robert’s passing. The work is a visual narrative that charts alternate histories of both Robert’s own family (the work that is seen throughout the book was supposedly made by the hand of Ruth Greisman, the actual name of Robert’s real-life aunt, whose creative/emotional life is largely fictionalized and expanded upon here) as well as of modern art, with brief appearances and fictional epistolary interactions, via Ruth, with Joseph Cornell and Marcel Duchamp, two figures Robert idolized. The pages reveal a wide spectrum of his working methods: reconfigured Victorian portrait paste-ups, brightly colored and thickly interwoven text-image spreads, pseudo-Surrealist typewritten prose-poems (“The peach sky is a peach, rippled by gravity at twilight”), marginal doodles recast as luminous glyphs, and stark collages that showcase the elegant stains and crumples of found strips of paper.

Since its publication, the book has garnered a handful of glowing reviews and something of a cult following within the small circles of art-book enthusiasts. In a jacket blurb, Maggie Nelson called Book of Ruth “an enchanting, mischievous, often deeply moving act of invention and homage.” In a review for the Los Angeles Review of Books, Jocelyn Heaney called the book “one of those rare events in art and poetry that actually inspires the reader to write, to create, to make something, and to document and even celebrate the many seemingly insignificant things that make up a human life.” Events intimate and grand have been held to celebrate his work at Printed Matter and at the Queens Museum over the past few years.

The fall of 2014 heralded a series of watershed moments in Robert’s expanding posthumous career. Siglio further cemented his reputation in print with two new titles: A Picture is Always a Book, an extension of the strange semi-autobiographical terrain charted in Book of Ruth (co-published with Smith College Libraries), and (in collaboration with Ugly Duckling Presse) Songs of S., a collection of poems. And on September 12, Hampshire College unveiled the Robert Seydel Reading Room, a space that gathers over four thousand volumes from the artist’s massive and stunningly eclectic personal library, for academic research and general public use.

***

I remember that once, during a meeting to discuss the progress of my thesis, about a month before my deadline, Robert told me that he had been lying in bed at 4 a.m. the night before, unable to sleep after an evening of working (and after drinking his pot of night coffee, presumably), thinking about new routes for my project to take. He pulled out well-thumbed copies of Edmond Jabès’ The Book of Questions and Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet from his shoulder bag, told me that he was reading them side-by-side, and that I should consider re-writing my text, some eighty or so pages at that point, under the guise of a pseudonymous fictional character. I declined the offer.

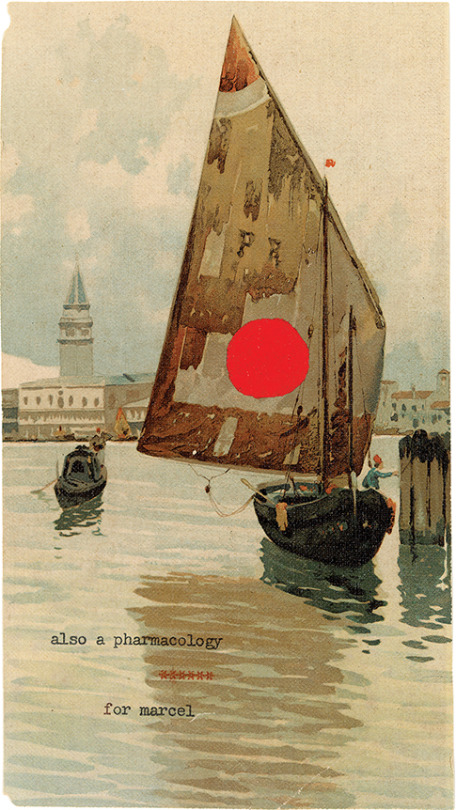

Just as Pessoa worked through heteronyms in his poetry and fiction (effectively writing within the perspectives of fabricated authors, each with their own unique styles and biographies and modes of behavior), Robert fit his constant activity into the confines of a range of semi-autobiographical characters and complex narratives. In both Book of Ruth and A Picture is Always a Book, Robert works in the reimagined persona of his aunt Ruth, who was a bank teller, a Sunday painter, and a resident of Queens, New York. The location is crucial to the fictional origin story of this intricately folded cosmology: his actual aunt Ruth and uncle Saul lived in a house in Queens. (Robert has an unpublished series of works that deal with the interchangeably spelled Saul/Sol, and which spin out from his real life as a plumber to encompass The Canterbury Tales, Paleolithic art, an invented Hall of Scatology, and the “history of the labyrinthine world of sewer construction, as well as of labyrinths in general,” as he once wrote.) In Robert’s fictionalized reworking of Ruth’s life, the two lived in close proximity to Joseph Cornell’s legendary home studio on Utopia Parkway, in Queens, and much of “Ruth’s work” was supposedly sent to Cornell through the mail as love letters and collage-poems, while others were intended for Marcel Duchamp, who was introduced to Ruth through Cornell. Some of these collages and poems were purported to have been discovered among the scraps, journals, and ephemera in the Joseph Cornell Study Center at the Smithsonian, which then led to the eventual discovery by family members of a sprawling cache of unknown works by Ruth tucked within in a suburban New Jersey garage. In Book of Ruth and A Picture is Always a Book, his collages and poems thus act as faux-archival evidence of an epistolary romance that never happened. As with all of Robert’s work, there is a nesting-doll aspect to the ways that fiction and autobiography, art history and family history, are all melded together in the books.

In Songs of S., a gathering of pure-text poems, though accompanied by a separate pamphlet of colored-pencil drawings, Robert works in the method of the alter-ego “S.” In the preface of the book, he writes that “not much is known about him as a person—there are some hospital records to consult and various official documents (tax records, census records), and a few saved letters from presently unidentifiable people.” Yet S. seems to have a biography that parallels Robert’s: he lived in Amherst near Emily Dickinson’s house, wrote prolifically, kept a journal, and made collages and drawings at night.

Robert had an array of other personas that he worked through, none of which have taken center stage as of yet in the published works—Droon, Eckstein-Sousa, R. Welch, and Sol/Saul, among others, each with their own professions, habits and biographies. In his only published interview, conducted by Savina Velkova in 2010 but posted on the Siglio website after his death, Robert stated that “art has always seemed to me a kind of exit out of the self, a way to get beyond the self. I don’t think I’ve ever really understood why ‘self-expression’ is an attractive motivation for making art, which is how students so often speak about what they’re doing.”

***

In the same way that his serious reading bled into his fictional art-historical narratives, Robert was also constantly looking in books for precedents of the kind of strange hybrid form that he was working within—the kind of unacknowledged inspirational figures that the OuLiPo call “anticipatory plagiarists.” Robert was a great theorist of the artist-writer, the makeshift art-historical sub-tradition that he was articulating as he went along. In his excellent essay on the poet Keith Waldrop’s own visual collage work (published as Several Gravities, which Robert edited for Siglio as one of the press’s earliest titles), he writes:

From Wang Wei and William Blake to Hans Arp and Henri Michaux, distances of cultures and period seem to matter less than the impulse they share: to bind up the verbal and visual and to enunciate across linguistic and pictorial fields a shared heritage, at the origins perhaps of an alphabetic writing in glyphic mark- making.

In this tradition, both writing and art are tied up in a blended form, one that reaches far back into prehistory, pre-dating both visual art and literature as distinct categories, and occasionally rises to the surface in the work of select poets and artists.

As he describes his own process in the artist’s statement for the CUE show: “Making proceeds for me by serial invention, from piece to piece and across time. The means are collage and drawing, picture as writing, scaled intimate and to the hand. Essentially I want to write an art, to make of the visual a kind of text, and have it be as well a poor art, assembled from scraps.” Robert was resourceful, using many of the same tools that writers traditionally used before computers: paper, scissors, glue, typewriters, erasers, white-out, rubber stamps, markers, pens, and pencils. (I remember him telling a studio art class about the importance of using whatever resources are cheap and readily available within one’s art practice. He told us that when he had come down with a recent cold, he even used his snot as adhesive for a collage.) This use of standard office supplies was more than mere thriftiness, though: Robert used a writer’s tools to essentially write his collages and journal his visuals in the knotbooks.

In the afterword to Songs of S., the poet Peter Gizzi writes eloquently on the textual qualities of his departed friend’s collages: “I’ve often felt that one can read Robert’s visual collages like poetry, that is to say, their private annunciation, gnomic pressure, and animated imagery are all techniques shared with the composition of poetry.” The source materials that Robert used, each with its own history of quotidian scuffings and natural decay, are able to behave on the page in a way parallel to that of a written text and can act as vehicles for meaning in their own fashion.

As he considered the production of his visual art to be a form of textual unfolding, Robert’s work benefits from the kind of close reading usually saved for writing; a viewer can effectively “read” the layering of found images in Robert’s collages. Take, for instance, Ruth’s animal emblem of the hare, which appears throughout Book of Ruth. Though it is always a distinct image of a hare taken from a variety of sources from different eras, its continual reemergence in the book feels like a motif in the way that one can trace a metaphor coursing through a novel or an image patterning a poem. The color red is also prominent—it sweeps along the edges and seeps into the backgrounds of many of the collages and texts—as are flattened wads of street detritus, drawn and ink-stamped stars, and a range of pasted-over and newly masked heads from turn-of-the-century photographic portraits.

The images often have the appearance of having been crudely created by the hand of an eccentric outsider—many of the collages initially look messy, with their forms hastily outlined in ink, and the pencil-drawn figures could be the marginalia of a preoccupied daydreamer. The immediately naïve face of the work was, in fact, a well-studied innocence on Robert’s part. He was something of a scholar of outsider art and art brut, often referencing key figures like Jean Dubuffet and Henry Darger, as well as more peripheral figures like Adolf Wölfli and Aloïse Corbaz. He also had a serious interest in early cave paintings and Native American pictographs: he read field guides for the preserved sites of the Southwest and made regular trips during school breaks to visit some of them. I even recall him talking about wanting to establish a summer residency in New Mexico or Arizona, where students could spend the day looking at petroglyphs and pictographs and then return to their studios to work on related art and writing projects.

This broad dilettante knowledge of both literature and art history soaked into the visual pieces in numerous ways. Robert’s reappearing cartoonish figures, drawn with perennially bulging eyes and stubby ears, look like an homage to the bunny-like creatures that peered through Ray Johnson’s work some fifty years earlier, and the pages dense with stamped letters carry on the dynamic typographic traditions that began with Dada and Futurism. The geometry of Kurt Schwitters’ merz pieces carry over to many of Robert’s denser collages. A found scrap of creased paper covered in inked markings looks like a replica of the calligraphic imagery of Henri Michaux. Robert’s idols Joseph Cornell and Marcel Duchamp appear everywhere, too, in the “plot” of the Ruth narratives, as well as in more general stylistic inclinations.

Also a pharmacology, for marcel” by Robert Seydel, 2003. © the Estate of Robert Seydel. From Book of Ruth (Siglio, 2011).

***

If the newly published books are one step toward giving Robert some well-deserved recognition as a collagist and as a writer—and as he was astoundingly prolific in a relatively short amount of time, there will hopefully be many more books and shows to come—his memorial library is a different kind of gesture. The Reading Room at Hampshire reveals some of the intellectual underpinnings behind Robert’s artistic practice, something that tends to be undervalued in the legacies of visual artists. We can visit the Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin to study the personal libraries of many novelists and poets, but we are mostly in the dark when wondering what an artist may have read during the peak years of his or her working life. (The rare exception to this seems to be the sculptor and land artist Robert Smithson, whose extensive library, filled with science-fiction paperbacks and geology tomes, was cataloged in its entirety after his death. How great would it be if there were decentralized memorial libraries for visual artists scattered around the country? So many art-historical questions could be answered. Was Eva Hesse reading up on aquatic plant biology while making her radiant, anemone-like sculptures? What kind of texts on cybernetics was Nam June Paik reading when he pioneered the field of video art?)

I visited the Robert Seydel Reading Room at Hampshire College last winter on a day when the bright sun was casting through floor-to-ceiling windows onto a dozen students working quietly, or soundlessly sleeping, within the alcoves of this book-lined environment. The school has taken Robert’s truly immense personal library—transposed from the apartment where he once lived alone among his books—and placed it in a clean and airy Brutalist space on the college library’s second floor, filled with clean-lined bookcases, benches, and desks made of reclaimed wood and metal piping.

As it has now been four years since his death, it’s likely that none of the students in the room, or in the surrounding college, ever had the chance to know Robert, or to be motivated by his singular dedication to art. For them, he may be no more than a name, a faceless former teacher who amassed the eclectic collection on the surrounding shelves. But the reading room at Hampshire is preserving an important aspect of Robert’s artistic process: reading is always an intimate act, especially for a person who led such a solitary creative life, and his work was the result of a private dialogue with a range of artists and writers, with influences echoing off of each other through his daily working cycle, the nights spent processing the texts ingested in the morning.

If one of these students were to close her laptop and open any of these books at random, she would notice a small image stuck to the front inside cover, an ex-libris (a bookplate “from the library of”) showing one of Robert’s collages from Book of Ruth: a wadded scrap of paper shaped as a hare, leaping over a bleached streak rising out of the lower corner of the image like a solar flare and into a dark night background illuminated by a thick gob of red paint, a single glowing scarlet star.

I like to think of an ex-libris as placing a signature over the breadth of an entire collection, designating that particular spectrum of interests as unique to its singular, original reader. In my own history of checking books out of public and university libraries, I’ve often found that I routinely gravitate, entirely by chance, to certain books stamped with the ex-libris of a few reoccurring ghostly names, as though they were my unwitting guides down certain rabbit-holes of reading.

A bookplate is a papery headstone multiplied many times over, travelling to readers whose eyes will one day trace the same lines and whose fingers will thumb the same pages as the departed once did. Walking through the Seydel Reading Room is like tracing the kind of connective tissue that Robert saw between the disparate topics, genres, authors, and artists: the reading room is the physical realization of the wildly associative mind of a true artist-bibliophile. And the books in the Seydel Reading Room will eventually circulate through the regional university libraries, and will unknowingly connect future patrons back to Robert’s small book-filled apartment near the Dickinson homestead, where he smoked and read each morning, and collaged through the night.