An Interview with Short Story Writer and Editor Lincoln Michel

I’ve known Lincoln Michel for nearly a decade. We got our MFAs together at Columbia where we became close friends—drawn together not only by our mutual love of Twin Peaks and heavy metal, but what emerged as a profound aesthetic kinship for the high camp of popular genre fiction (Stephen King, Ray Bradbury) alongside cerebral classics of the uncanny (Franz Kafka, Thomas Bernhard, Bruno Schulz). In our time together at Columbia and in the years that followed, we discussed books and traded book recommendations prolifically, our sphere of influence widening to include a host of 21st century experimenters (Lydia Davis, Diane Williams, Laura van den Berg, Brian Evenson). All this went into our stabs at short fiction—for my part sprawling penny dreadfuls with byzantine language and entropic plotting, for his, hyper-real, discomfiting vignettes that laid bare the strangeness of everyday life.

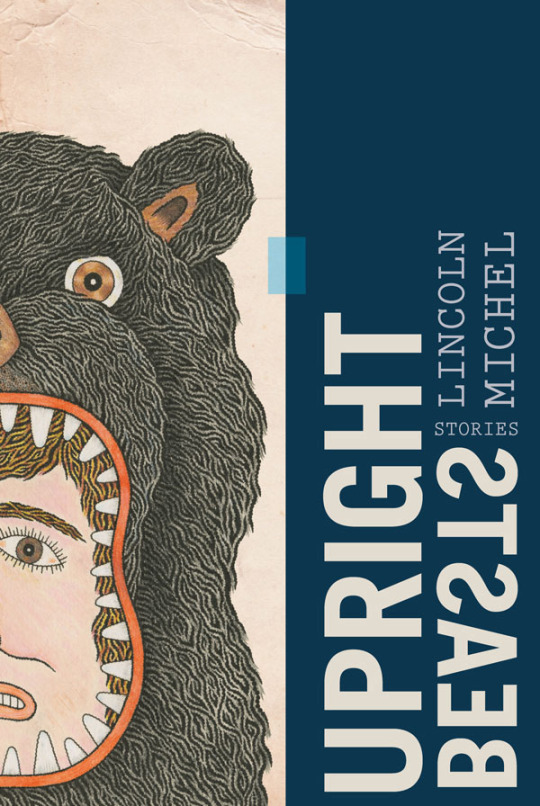

In October 2015, Lincoln published his debut story collection Upright Beasts with Coffee House Press. I was struck by both the consistency and diversity of his vision. To read Upright Beasts is to enter a disconcertingly familiar world—one where isolated schoolchildren enact grand tragedies of violence, alienation and thwarted intimacy; where beleaguered Joe-Schmo’s double-down on troubled notions of masculinity; and where solipsistic twentysomething’s come into confrontation with hideous beings from provinces beyond human knowing. To re-read the book was to read it afresh.

Lincoln is also a stylist as highly layered as he is restrained, with diction so sharp it can skin you alive, recalling the best of Italo Calvino, Kathryn Davis, Denis Johnson. Not to mention the fact he’s incredibly funny—Jack Handey on a bad shroom trip—with salvos that crumble upon the abyss that yawns beyond even the most ordered life.

Over two weeks in October we emailed back and forth about Lincoln’s debut collection, the usefulness of genre traditions, demolishing readers’ expectations, and the nourishing persistence of the uncanny in day to day life.

—Adrian Van Young

I. HILLS COVERED IN KUDZU

THE BELIEVER: One thing that struck me were the subdivisions in the book: “Upright Beasts”, “North American Mammals”, “Familiar Creatures”, and “Megafauna.” They’re subdivisions that could serve to separate the stories according to genre, or how they move from realist into fantastical and then back again—or even the tone, like movements in a musical piece.

Can you describe some of your thinking behind making the conscious decision to group the stories together in this way?

LINCOLN MICHEL: The ordering of the collection is definitely something I struggled with for a long time. I always knew that I wanted an eclectic collection that combined surreal stories with realist ones, flash fiction with long stories, and stories in different genres and styles. I’ve always admired authors who try lot of different things, and I write in a lot of styles and genres anyway. Making that work was hard to do. Eventually my editor, Antira Budd, and I settled on four sections, little books within the book. I think that framing goes a long way toward shaping how you read a text. My hope is that the structure allows the reader to move between styles and stories in a way that isn’t unpleasantly jarring (though some pleasant jarring is always welcome).

Music is a nice metaphor, and I definitely played around with tone, pacing, and varying the length of pieces as one might with a mixtape. Combining different voices in interesting and surprising ways is something I’ve always loved doing as an editor. Also something I enjoy reading, and why I love lit mags.

Also, the divisions are not strict. There are, for example, some unreal stories in the North American Mammals section, and some genre-influenced stories in other sections than Megafauna. (“Genre” and “literary” are incredibly confused terms which people use with increasingly contradictory definitions, so I’m using that term with some hesitation.) I wanted each section to have movement and variation too, while still cohering as an individual mini-book.

BLVR: I was speaking with a mutual acquaintance of ours recently who has also read the book, and with whom you grew up. She commented how strange it was for her to read the book because so many of the stories seemed to refer directly to images and instances from the childhood you shared. Can you comment on how drawing upon the totems of your childhood in the South has gone on to inform the collections’ notions of the uncanny?

LM: I grew up outside of a town called Free Union, which is outside of Charlottesville, and then moved halfway through my childhood to a neighborhood also outside of Charlottesville.

That first house was surrounded by eighteen acres of woods and our only neighbor was a cow pasture. The neighborhood was also surrounded by a lot of woods where we played our various games and planned our various pranks. As I said, I love a lot of Southern writers and I’m sure some Southern syntax and locutions have naturally worked their way into my language. But I think the bigger influence is nature—the woods, the creeks, the muddy ponds, swarms of bugs, and bright newts and tadpoles and ever-present deer.

I’m not a writer who is interested in autobiographical fiction. I am interested in using moments, actions, or objects from real life in new ways through fiction. Those locations that made up my childhood—neighborhoods surrounded by forests, swimming holes in the mountains, hills covered in kudzu, train tracks winding through the outskirts of town—are images and settings where I definitely return. They’re imbued with private meaning and mystery for me, and that leaks into the fiction and helps create pools of uncanny in the text. Nature is inherently alien, absurd, and mysterious—at least to me—and childhood is a dark and unreal time. The combination of those things can be powerful, I think.

II. FOSSILIZED PIZZA CRUSTS

BLVR: It can also, of course, be funny—especially retrospectively. In the book, you have a lot children who behave like adults, and adults who behave like children. George Saunders has a quote about humor in his stories that I love: “Humor is what happens when we’re told the truth quicker and more directly than we’re used to.” That’s happening here, but the humor I find in your work is very specific. The book describes a lot of extreme circumstances in a casual way that’s very conspicuous.Who are some of your influences?

LM: Humor is really important to me, and the nexus of humor and the uncanny, or comedy and the darkly weird is my favorite thing. My favorite dark and weird writers—Kobo Abe, Franz Kafka, Flannery O’Connor, Shirley Jackson—are all extremely hilarious. And my favorite comedies—like Mr. Show or Kids in the Hall–infuse their humor with the bizarre. I like that Saunders quote, it reminds me of a quote I heard that I believe was said by Chris Rock. To paraphrase, it was that comedy is saying the most awful things with a completely straight face. That’s a way of delivering truth unexpectedly, but also gets at something I think is true, which is that the line between tragedy and comedy is very thin. It is really just about how something is framed and delivered. Another relevant quote here is from Mel Brooks: “Tragedy is when I stub my toe. Comedy is when you fall into an open manhole and die.”

I’ve definitely been influenced a lot by comedians. Bob Odenkirk, Amy Sedaris, Jack Handey, the monologues of Kids in the Hall, the old albums and books by Steve Martin.

I don’t know if my sense of humor is unique, but I do try to employ linguistic and syntactic maneuvers from comedy for other purposes. That is to say, to take the pacing or the word choice from jokes, but instead of a punch line, the sentence ends in some kind of horror, sadness, or confusion. Doing that still adds humor to the work, but it is a subtler humor—a tragic comedy running through the veins of the text.

BLVR: That is absolutely the kind of humor I’m talking about. You wield your language very bluntly in these moments. For instance, from the beginning of “Halfway Home to Somewhere Else:

It was one of those muggy days where the sun licked you all over like a stray dog. The kind of day that wore on you. All you wanted was some lemonade, but the little boys and girls were inside with the TV and AC, and the paper cups were being chewed apart by angry rats.

Or, from “If It Were Anyone Else”: “Gray pigeons walked around us, knocking their heads down at fossilized pizza crusts. It was quiet and peaceful.”

Notwithstanding that both of these passages involve creepy animals, there’s also a kind of hyper-reality to them—a grotesque cartoonishness. What do you think that kind of reading experiences can yield, emotionally or otherwise?

LM: I appreciate the question, because I’ve become increasingly interested in the effects that fiction can have and feel like it’s an under-discussed topic. In most craft essays and creative writing classes, the focus is on plot or character or maybe structure. But there’s very little discussion of what techniques can bring about this or that effect. What objects and actions create a sense of “the uncanny”? What language can impart a sense of “the sublime”? How do you summon “terror” instead of “horror”? What makes a character “grotesque”? Or, hell, how do you make a reader laugh?

I don’t have the special answers to those, but I wish it were discussed and studied more. Personally, I find that reading about the philosophy of aesthetics to be far more useful to my writing than most craft essays that just repeat some old clichés about writing your darlings and killing what you know. Or is it the other way around?

I’m not sure I want readers to be uncomfortable—please, sit in a nice chair with a cup of tea while reading my book!—but I’m definitely interested in the effects that a more unstable narration can yield. I like to play with shifting emotions, and shifting narrative logic. I like art that kind of crumbles our sense of reality and rebuilds it into something new. For me personally, I really like a balance between the unreal and logical, a world that’s a distorted version of our own but not an entirely separate one.

Straight realism rarely interests me artistically. I get more than enough “reality” in my Twitter feed every day.

BLVR: I agree that talking about effect is underdiscussed. To me that, in many ways, is the essence of the “craft-oriented” approach to writing, and I always try to impart it to my students at Tulane. Like, forget the “what” and the “why” of this piece of work and concentrate on the “how”—how it is made technically, but also how it does to the reader emotionally and psychologically, aesthetically, whatever, what it does.

These stories range widely in “effect”—almost as widely as they range in genre. Do you see “effect” and genre as being interrelated? Do you think that situating a story within a specific genre tradition can heighten its “effect”?

LM: Yes, totally. The “how” a piece works is far more important to me than the “why”—typically some reductive interpretation or simple message. My underlying aesthetic belief is that great art is ambiguous and provokes multiple feelings and suggests multiple meanings.

I’m thinking of the grotesque (a character who provokes both disgust and empathy), the uncanny (the familiar becoming strange and the strange becoming familiar), or Todorov’s concept of the fantastic (fiction in which it is intentionally unclear if supernatural events are really occurring or merely in the imagination of the characters).

For certain effects or technique, genre certainly is a factor in their, uh, effectiveness. The fantastic, as just described, requires supernatural events to at least seemingly occur, so requires having at least one foot in one unreal tradition or another (fantasy, horror, magical realism, etc.) The uncanny is an eerie effect, so is suited to work that is in some sense horror.

That said, genre is something I find really fascinating and really misunderstood…or at least misused. I’ve always had a bit of a foot in both the genre world and the literary world, and both worlds speak about each other–and themselves!–in ways that really don’t gibe with literary history. For example, people on both “sides” frequently speak as if “literary” = realism or mimetic fiction (genre fans often refer to it more disparagingly as “mundane fiction”)… in effect erasing the Kafkas, Calvinos, Pynchons, Carters, Marquezs and so on from literary fiction history. Or else they shuffle those writers in genre traditions that they clearly weren’t writing from and with writers they really weren’t in conversation with. (That’s ultimately how I view genre: as traditions or conversations between writers, readers, and critics.) You know, that silly game of claiming that author x is “really” science fiction or that author y is transcends genre so is “truly” literary.

I know that a lot of writers and critics love to scoff at genre as just being “pure marketing” or something. And that can be true many times. But genres can also be really vital and intriguing traditions, different veins pumping literary blood into your art.

BLVR: Genre as traditions or conversations between writers is a lovely way to put it. Interestingly, though, you seem to be saying that while genre distinctions hinder us, they’re also very useful in the process of not only discussing but producing strong and dynamic writing. In other words, working within a certain genre or tradition can set up a certain set of expectations in a reader that you can, then, subvert as the writer. Something that’s familiar as science fiction or fantasy, for example, but rendered strange through the ambiguity or mundanity of traditional literary fiction. Of course, the cocktail pours both ways. Traditional literary fiction, which is a genre in itself, rendered strange through the trappings of horror or Gothic romance or something.

LM: These are issues I think about a ton. It’s true that we don’t normally think of genre as tradition in literature, but then again we sometimes do. Normally we think of “magical realism” as a tradition that grew in a specific time and place in Latin America, and most people recognize “high fantasy” of the Tolkien sort as, well, descending from Tolkien. I also think that we have this contextual understanding in music genres. Any music fan knows that a brash song with loud guitars could be a 70s punk rock song, a 60s garage rock jam, an 80s metal tune, or a 90s grunge rock song—among other choices—depending on the actual context of the song. Right? There isn’t something inherent to loud guitars or snotty lyrics that makes a song punk, at least not exactly. Granted, even in music there are a few bozos who try to say things like “Bob Dylan invented rap music with ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues’!”

When someone says “Magical realism is merely fantasy that critics like!” I frankly think they come off like the hipster trying to argue Dylan invented hip-hop. Kind of clueless.

Science fiction, fantasy, and horror are often grouped together (sometimes simply as “speculative fiction”)—and rightly. There is a ton of overlap between writers and readers in those genres. But those things are not inherently tied together. Horror is grouped with SF/F because of actual literary history—including the influence of H.P. Lovecraft, Stephen King, and horror that combines science fiction and/or fantasy. In an alternate literary universe, horror might have been grouped together more closely with crime fiction and we might have some umbrella genre called “deviant fiction” (or something) used as commonly as “speculative fiction.”

Your point about how working in a tradition can set up expectations that you can undermine or exploit is exactly correct. It’s similar to working in a form (a sonnet, a novel in letters, whatever): it gives you a structure that you can play off of in various ways. I get the desire to claim that genres are all marketing and mean nothing, but I think it is pretty dishonest. If you read a hardboiled noir meets science fiction novel (Lethem’s Gun, with Occasional Music is a fun one of those), the book works by playing into or off of your understanding of the genre. Someone who has never read or watched any noir or science fiction will not get nearly as much out of that book. The book is directly in conversation with different genres. And that’s a good, not bad, thing!

III. SUBVERTING THE GENRE

BLVR: We’ve discussed in the past how distinguishing between “commercial” fiction and “literary” fiction might be more apt in many ways, especially insofar as “genre” seems to get subbed in for “commercial” a lot of the time. Could you expand on this notion with some examples, maybe?

LM: Right, so part of the problem with all these genre conversations is that the terms are used in a lot of different ways. “Literary” is used to both mean something of simply high artistic merit, however that’s defined, and also to mean a kind of quiet domestic realism. “Genre” is used to mean both formulaic low-quality work, and to mean just anything that falls outside of the aforementioned quiet domestic realism. Then it is also used as a synonym for commercial” or “popular” fiction. The last definition of genre is, I think, simply unuseful.

Tons of work that we’d universally call genre—various subgenres of fantasy and science fiction, say—only have a niche audience and are basically never commercial best sellers. (There’s a similar conflation of “genre” with “accessible to the mainstream” that’s also bunk: a 1,000 fictional history book of a fantasy world is clearly a genre book but is also not aiming to be accessible to Joe Schmo. And that’s totally fine, just as it is fine for an academic postmodern poet to not be aiming for Joe Schmo. Schmo has plenty of books aimed at him as it is.)

But the other definitions are true to various degrees. There is essentially a genre of fiction, sometimes called lit fic, that’s basically a bunch of quiet domestic realism. It shares as many tropes and as much history as fantasy or romance. On the other hand, there is also a tradition of innovative, artistic fiction that has little to do with so-called lit fic and frequently little to do with realism and yet is always called “literary fiction”—Nabokov, Kafka, Woolf, Borges, etc. Similarly, there are whole industries based around pumping out formulaic genre work that intentionally meets—instead of challenges—reader expectations. The fast food of the book world, basically. But there is also, within the various genres, innovative, artistic, and challenging work: Le Guin, Dick, Chandler, etc.

My basic feeling is that latter group is simply simultaneously “literary” and “genre.” There’s nothing really more “literary” about Zadie Smith and Roberto Bolaño than Gene Wolfe and Samuel Delany. We could argue the merits of them, of course, but they are all equally “literary” in the sense of writing challenging, boundary-pushing, and artistically innovative work.

BLVR: By the same token, though, as we’ve also discussed, the mashing up of “literary” fiction and “genre” fiction has nearly come to occupy its own niche—is becoming a genre in and of itself. It seems like every month I’m hearing about a new book of stories about mutant caterpillars who discuss Derrida in the shadow of the Eiffel Tower, or storybook grandmothers who are also werewolves. Upright Beasts, it strikes me, is not such a book, though it could be mistaken for one at a glance. What would you say in response to this kind of over-saturation? What writers do you see as pushing the “boundaries” even further?

LM: I’ve always found it creatively inspiring to have a structure of some sort to play around in and push against. There is a story in my collection that’s entirely dialogue and another in the form of a note on the type. The two of them sit along stories that feature aliens or that are pure domestic realism.

Writing a story that takes, and hopefully subverts, the structure of a fairy tale is, for my writing process at least, pretty similar to writing a story that’s composed of emails or one that features no dialogue.

I certainly hope that my book doesn’t read like the kind of purple-giraffes-going-to-Juilliard-to-learn-the-ukulele kind of story. But to me, that isn’t about genre exactly. Those kinds of stories hare crossed over from the mysterious, the fantastic, and the weird into dull land of the whimsical and the twee. To me, there is a world of difference between that kind of work and the writers I love (Kobe Abe, Franz Kafka, etc.). The gulf between them is filled with darkness, with real sadness, and with the blood and dirt and sex and anger. That is to say, I think that you tip over into whimsy when you lose anything to weigh it down and anything, lose all the grittiness of life, so that all you are left with is the surface level “wackiness” that’s more like a toy commercial than art. Whimsical fiction just trickles away on a stream of indie rock kola bears playing ping pong into the ether. It doesn’t get its teeth into you.

Another kind is work that isn’t whimsical, but also doesn’t really engage with the aforementioned traditions and conversations of the genres. Great genre-bending fiction subverts and complicates the tropes in any number of ways, but it also understands them.

I think the writers I love who push those boundaries today—Kelly Link, Julia Elliott, Charles Yu, Margaret Atwood, Samuel Delany, Helen Oyeyemi, Brian Evenson, you, etc.—are likewise lovers of the genres and underpin their work with that darkness and sadness.

BLVR: I agree that that loving inclusiveness is important when it comes to genre-bending. Which brings me around, circuitously, to your role as an editor at Electric Literature. I’ve always been impressed with your outspoken eagerness in beginning to instigate some sort of change to make the literary community better reflect the world—more fully welcoming women, people of color and LGBT individuals. What are some strides that the lit community has made in this regard? What is some work that we have yet to do?

LM: I do think diversity is extremely important, but I don’t think I deserve any credit on this front. I do consciously try to read diversely, publish a diverse set of writers, and promote diverse work that inspires me. I think we do a good job at Electric Literature, publishing and covering writers of different ethnicities, different nationalities (we have a great series currently going called The Writing Life Around the World), as well as different genres and aesthetics for that matter. But I think that’s really a bare minimum.

Diversity is important for all the obvious reasons, but I also care about it for selfish reasons too: reading diversely and getting a variety of perspectives helps expand you, helps you see more and understand more. I go to art to learn to see and think in different ways. I want more terrain added to my mental map. I can’t imagine wanting to fence off the world of fiction into one tiny plot.

BLVR: It’s a funny and very particular form of myopia. And so, while I can understand your not wanting to take credit for doing the bare minimum, I’ll rephrase and say that I’m always impressed with your empathy, as an editor and a writer—in how you attempt to inhabit perspectives different than your own.

A lot of the female characters in Upright Beasts were very well drawn, which isn’t something you always see from male writers. Both you and I have made a lot of attempts in our work to write across gender—you in this collection and your novel in progress, Doom Mood, and me in my forthcoming novel. What do you feel is the key to writing across gender successfully?

LM: I do write across gender, and try to write about characters of different backgrounds. I think that fiction has various roles to play when it comes to diversity. One of those roles is representing different experiences, so that readers can see themselves reflected in art and/or get into the mind of people who aren’t like them and hopefully learn some empathy. I’m not sure that’s my role, and I’m not trying to appropriate other people’s experiences. But fiction also has a role in normalizing different experiences. You know, the way that there’s an argument that The West Wing and various films helped normalize the idea of a black president for white people before Obama, or how the representation of gays in media helped shift the public opinion on gay marriage. So I think about that some. But more so, I just want to have a world that’s populated by the actual diversity of human life. I’m sitting in an office surrounded by people of different races, creeds, gender, and backgrounds. I think there are twelve people here currently, and only two of us are white men. This is my everyday experience, so it would be pretty weird to only write about white male characters from Virginia with a first name that’s the last name of some president. Right? It really isn’t an agenda. It’s just actual life.

I’m really glad when women tell me that I’m good at writing female characters. I don’t really have much of a trick there. My honest answer is that I don’t really make much of a distinction between male and female characters, to the degree that I quite literary switch the gender of characters during drafts without making many other changes. For example, the story “The Room Inside My Father’s Room,” about these fathers who keep building smaller and smaller rooms for their sons to live in, was originally about mothers and daughters. I actually think swapping genders (or races or ages or whatever) is a great way to shake up a story and see it from a new angle. In my in-progress supervillain novel, DOOM MOOD, I swapped some genders a couple times. Those characters are playing around with archetypes, and that was one technique to subvert expectations. In general, it’s a useful writing practice for writers to try.

BLVR: Having read what I’m assuming will be an early draft by the time you’re finished, I was once again struck by the madcap amalgamation of genres. It’s a sort of satirical science-fiction body horror superhero novel with strong Lovecraftian and/or Bernhardian elements—one of the most bizarre things I’ve ever read from you, and that’s saying a lot. I wouldn’t call it commercial, though it does move along at a clip. Can you describe briefly the process by which you conceived of DOOM MOOD and how that conception evolved as you continued writing?

LM: I’m glad you like it, but don’t tell my agent it’s not commercial! Seriously though, I feel like I could try for some highfalutin explanation of how DOOM MOOD is a postmodern deconstruction of comic book storytelling, a narrative mode that’s increasingly dominant today… and that’s kind of true, but really I’m just writing what I find interesting and think readers will find interesting. Subverting tropes and expectations is always going to be more interesting than giving the reader exactly what they’d expect. To me, having a supervillain go on a Bernhardian internal monologue rant is just more enjoyable than writing it straight. (Plus, the straight style of comic books works on the page because of the art, you need something different for prose.)