Stories of Self is a twelve-volume essay series by Scott F. Parker that explores the nature of the composed self through conversations with artists working in a wide range of media.

Ashamed, but Undaunted: Autotheory with Maggie Nelson

When I got to breakfast with Maggie Nelson at her hotel down the street from the Minneapolis Convention Center, AWP was just getting underway. Downtown was a swarm of writers, excited, anxious, and trying to be in three places at once. Even in the dimly lit, hangover-friendly restaurant, the muted conversations had the air of attempts at good first impressions. I asked our waitress for the most isolated table she had as both Nelson and I declined coffee. Nelson, who hasn’t had coffee since 1996, asked for tea. Only the day before, I’d returned from Santa Fe, where I’d been hiking and talking Buddhism with Stephen Batchelor, and part of me wanted to still be there. I was one of those anxious writers, after all, the kind who felt more at home alone in the mountains than networking under fluorescent lights. This bled into my conversation with Nelson. After ordering, the first thing I asked was about her background with Buddhism, a key reference point in her book The Argonauts.

“I’m not a Buddhist and have taken no vows. I have no formal training whatsoever. In different periods of my life I’ve immersed myself in sitting practice, but I find as a reader that a lot of the conundrums that Western philosophy bashes its head against are very swiftly set to the side or resolved or happily ignored by Buddhist psychology or philosophy, so it’s a very rich field to me for that reason.”

One reason Buddhism is often not considered a religion is that, like a psychological school or a critical method, it works as a collection of texts that offers a way of seeing, a way of talking that can be employed independent of faith. Western philosophy similarly abjures faith, but rarely—going back a few centuries—attends much to well-being. One prominent exception to this history is the late Wittgenstein, for whom philosophy aims “to show the fly the way out of the fly-bottle.”

And reading Wittgenstein, Nelson said, “can feel like you’re reading linguistic koans. Wittgenstein might ask, ‘Can my right hand give my left hand money?’ or ‘How do you know that a stone can’t feel pain?’ There’s a tradition in Western philosophy that I’m attracted to—and that Wittgenstein’s a part of—that aims to clarify rather than make grand narrative claims.”

Grand narrative claims fell out of favor in most academic and artistic disciplines in the twentieth century. Even memoir, a form of writing that can seem dependent on a coherent narrative arc of self, embodies this movement; it comes alive at the fissures of its coherency: when a narrator is struggling to hold the self together in a text—for the reader’s sake if not also her own.

Nelson is more fluid than most memoirists in this respect, her “I” is more likely to follow a line of thinking than a line of narrative. The Argonauts draws from wide-ranging sources—psychology, literature, and criticism as well as Buddhist and Western philosophy—and employs “life writing” (her preferred term over memoir) mostly to illustrate or deepen a concern. To read Nelson as a memoirist is to consider the self as a cultural artifact, and one that, given culture’s many cross-vectors, is always in flux.

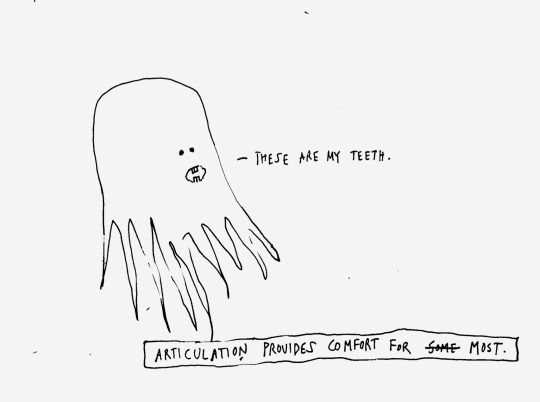

Harry Dodge, articulation (these are my teeth), 11″ x 9″, 2012. Ink on bristol board.

I got the impression as Nelson talked that she was scanning the many libraries in her head, choosing carefully which to reference. When the choice satisfied her and led to an idea she admired, she said the words quickly as if they could otherwise be lost. When she told me that in Buddhism “it would be expected that things be paradoxes or contradictions rather than these being signals that something has gone wrong,” her voice gave me all the commentary I needed about what a valuable model Buddhism was for her.

“You can have a discourse about the ego in Buddhism while fundamentally acknowledging it as an illusion that might obscure our connectedness. You can discourse about its features, but [the ego] is fundamentally presumed to be an illusion. There’s a kind of fluidity in Buddhism to the concepts that I think is helpful, rather than these reified, ‘I am writing about self; I am writing about other,’ which is a flawed dyad.”

Nelson offered me the last third of her fruit salad. Minneapolis was her first AWP and she had yet to make it from her hotel to the conference, preferring to lie low and peruse the books of French philosophy she carried with her. More to warn her than anything, I asked what it was like to be as one of the big stars at the center of the frenzy.

“It’s nice to hear, but I don’t experience my life that way, so it’s kind of like aporia. The thing that makes me happiest is a lot of people have told me my writing has given them permission to do or feel different things. If permission in the broadest sense is part of the locus of what is mattering to people about my writing, that makes me very happy. That’s one of the weird things about being here: as writers we’re such dopey people, the idea that there would be groupies is very funny. But there are encounters that have really mattered to me—there’s some of this in The Argonauts, which revisits many writers who mattered to me in my twenties, when I was more susceptible to writer-lore—I write about my first time seeing Anne Carson read, for example.”

It’s easy to lampoon a memoirist as someone who is motivated to have her story known, someone whose self-worth corresponds with self-exposure. For such a writer, fame isn’t an incidental (and hopefully profitable) by-product of writing, but rather the purpose. Reading Nelson’s work, one gets only the broad strokes of a biography. But despite narrative gaps, she will reveal life details such as anal sex on the level with the most eager exhibitionist. Except there’s nothing salacious in these disclosures. Nelson’s real, and more intimate, revelation is of her way of seeing. In Bluets she writes, “The most I want to do is show you the end of my index finger.” Doing so, more than anything, is what imprints her writing on readers and makes so many readers at AWP want to be in her presence. Knowing only so much about her, they feel like they know her. The effect of Nelson’s most distinct writing is that of a consciousness rendered, a consciousness you would be a fool to resist.

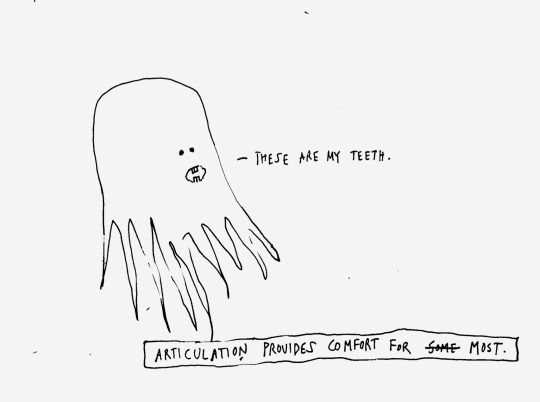

Harry Dodge, Some To Go, 11″ x 14″, 2004. Ink on bristol board.

“My writing isn’t descriptive of experience, it’s being written within experience so it has a heat or presence that is not the discursive mode of When I was five… Occasionally I will write paragraphs like that if there’s an anecdote I’m getting out. But that kind of writing to me generally feels quite deadening. I don’t trust the renarrativizing of the self in that way.”

The title of The Argonauts refers to “the passage from Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes in which Barthes describes how the subject who utters the phrase ‘I love you’ is like ‘the Argonaut renewing his ship during its voyage without changing its name.’ Just as the Argo’s parts may be replaced over time but the boat is still called the Argo, whenever the lover utters the phrase ‘I love you,’ its meaning must be renewed by each use, as ‘the very task of love and of language is to give to one and the same phrase inflections which will be forever new.’”

The Argonauts are the speakers, the lovers. They must produce fresh meaning from inherited language. On the first page of The Argonauts, Nelson attributes her writing to “Wittgenstein’s idea that the inexpressible is contained—inexpressibly!—in the expressed.” Later she writes, “for so long, writing has been the only place I have felt it plausible to find [my own me].”

As in writing, so in love; as in love, so in writing: “the romance of letting an individual experience of desire take precedence over a categorical one.” The themes and ideas explored in The Argonauts (queerness, motherhood, love, language, identity) are explored through particulars. “I am not interested in a hermeneutics, or an erotics, or a metaphorics, of my anus. I am interested in ass-fucking.” This goes for subject as well as object:

“You have your writing body, which is always writing in the present, and in some ways the action of the work is always the relationship between that writing body and its imaginings of the past. But it’s not the past itself that is the object of study. I’m not talking about what other people’s writing has to do. But in my writing, if I can’t feel a very alive sense of that relationship, then it will just feel dead to me to be discoursing on some past event. The scene of the writing body for me usually has to be present even if it’s ghosted. It is anyway, for everybody.”

As universality has fallen out of favor as a shared goal for writing, the various contexts of a piece of writing, including the circumstances of its creation, are increasingly understood as central to its interpretation.

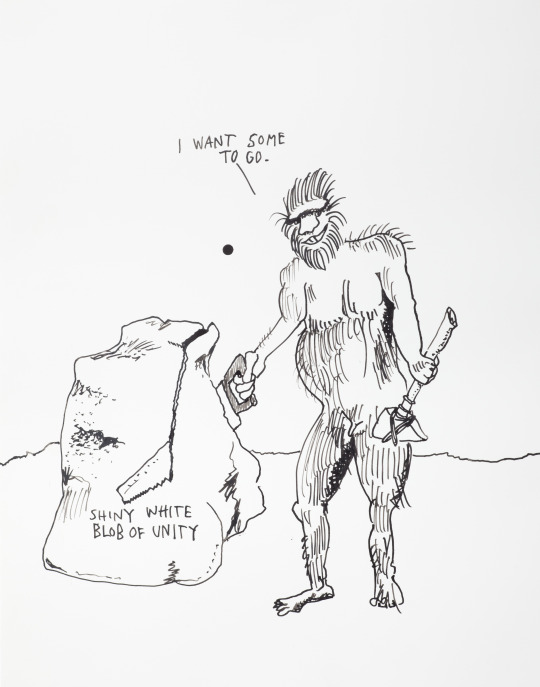

Harry Dodge, lobster boy (regarding articulation), 9″ x 12″, 2012. Graphite on paper.

“I’m not in love with the word meta and I’m not in love with writing that’s talking about its own composition, but I feel like most of my books do eventually stage and describe the staging of their writing. I like calling that attention. In Bluets I talk about how you can’t tell what mood something has been written in once it all moves together in a flow. And in Argonauts I call attention to the way you can edit yourself into a certain kind of boldness. Or a certain kind of uncertainty. But the reader’s not really privy to that process.”

Memoir can risk misleading. Unless otherwise dramatized, the narrative “I” tends toward cohesion. Moments of tension arise when that cohesion is threatened by trauma of one kind or another, but maintains more or less intact. The structure of a narrative concretizes the self around that which the author has expressed (plus the inexpressible therein). But the self is rarely so neat.

Here’s Nelson in The Argonauts: “When it comes to my own writing, if I insist that there is a persona or a performativity at work, I don’t mean to say that I’m not myself in my writing, or that my writing somehow isn’t me. I’m with Eileen Myles—‘My dirty secret has always been that it’s of course about me.’”

The writing is always about the author. Both when it is explicitly autobiographical and when it’s anything else. This anything else is where a fuller picture of the self begins to take shape—in the conscious interpretation and reworking of events, not in the events themselves.

The common-sense notion that a self is something you just have rather than something you perform doesn’t withstand much scrutiny. But it persists. We sometimes say, for example, “Be yourself,” as if this were something a person could ever achieve or escape.

“With memoir you’re presumed to have a self and that self is presumed to have—and note the word have here, possession—you possess a self and that self has experiences, which you then document. But there’s a way in which certain selves—I’m thinking here of Fred Moten’s writing about enslaved selves, Middle Passage onward—don’t necessarily follow a model of self-possession as much as of dispossession. And that changes everything. You can counter that with an I was dispossessed, now I’m coming into my possession model; I was blind, now I see; I was disempowered, now I’m empowered. You can read a lot of slave narratives in that light. ‘I didn’t have a name. I didn’t have a language. I fought to come to these things.’ But then there’s also a tradition of writing, of art-making, of being, that stays interested in the dispossessed self, which brings us back to a Buddhist sense of the self as undoing itself as opposed to consolidating. I think it’s inevitable that a book with a front and back cover is going to present a congealment of the self, it’s going to produce a sound, it’s going to produce a style, it’s going to produce an impression. But I think in the writing of it, there can be a very valuable interplay between possession and dispossession of the self that you can feel and maybe even get onto the page that is more interesting to me than a kind of ‘I have self, hear me roar,’ kind of writing. Of course, a Buddhist view wouldn’t necessarily emphasize the ties between dispossession and brutal power relations; it might just treat this as the condition of self, this kind of fluctuation.”

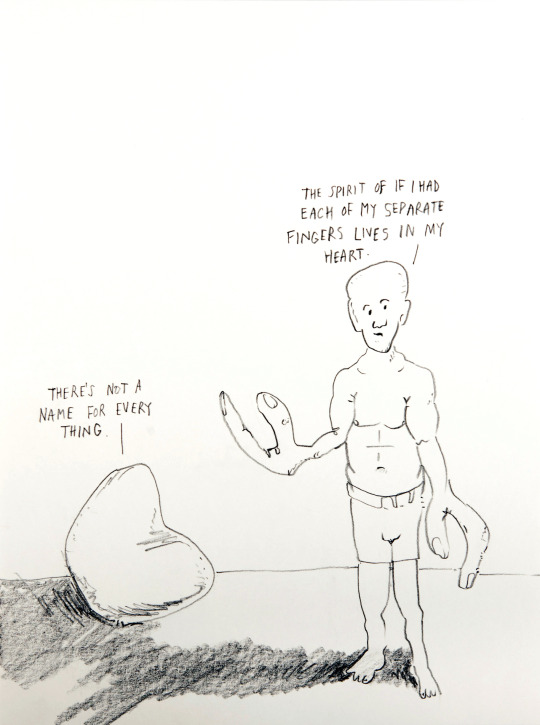

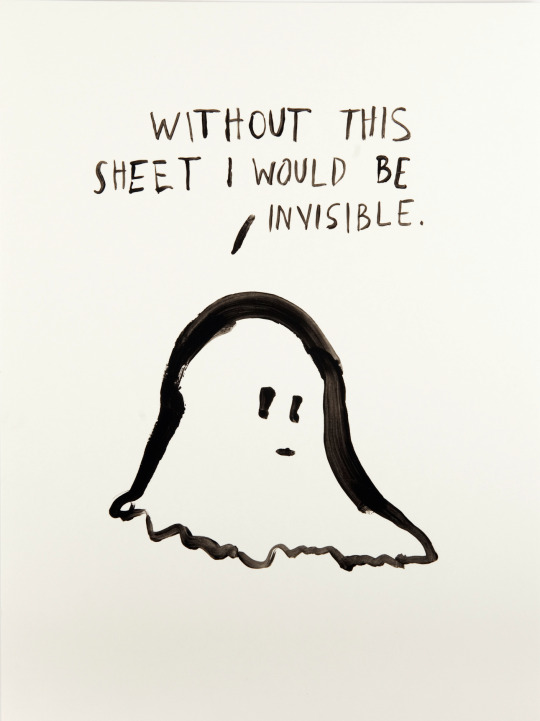

Harry Dodge, Invisible, 12″ x 9″, 2012. Ink and acrylic on bristol board.

Concerning the neologism “autotheory,” Nelson says, “I just stole it ‘cause I like it.” The word comes from Beatriz Preciado’s Testo Junkie and “it’s about yourself as a guinea pig for talking about larger cultural issues. Your body is not exempted from the conversation, your body is in fact a site of where these cultural, political, psychosexual whatever—where they’re playing out. But it’s a kind of willingness to offer up your experience as that guinea pig as opposed to a kind of narrative of a self.”

Autotheory says the narrative is in some fundamental way dishonest. To have a self is to admit of discontinuity, and recognize that one’s self-understanding can change according to events, mood, accident, and above all the object of one’s attention.

There is no self without other, no effect without causes, no stable “I” at the center of the storm. But still, a writer, at least to some extent, does decide what to write.

“So much of the discourse about memoir in this country is about what to reveal and what to conceal. I have no interest in that spectrum. When people say things to me like, ‘What does it feel like to put such personal material out into the world?,’ it isn’t a question that lands on a map I’m thinking about. I’m so focused on what experiences would be the best illustrations or ways in to the issues I want to talk about. I feel so confident that the task is about how best to get at the things that are interesting to me rather than think about a discourse of secrets or revelation or exposure.”

For Nelson, the real revelation is the courage and honesty to bear one’s consciousness at work.

“Honesty is a very interesting term. You can produce effects of honesty in a reader without necessarily having gotten as honest as you want. Honesty, the concept, presumes there’s a self that we know and that we’re choosing to either be honest or dishonest about. But the actual fact of writing, to me, is much more unconscious. You can produce many different truths, and then you have to choose which of those were defensive and which were rageful. Until a book is published I feel like I’m still writing to get to the point where—it’s not the most honest formulation as if the other ones were dishonest, it’s like if you were an undergraduate writing an essay and they say, ‘Okay, by the time you got to your conclusion you finally got to the most interesting point,’ it’s more like you just have to write to an interesting point. You could call that honesty or you could call that something else. A lot of the first things you write are just not the most interesting.”

For a few years after David Foster Wallace’s death I couldn’t click on a link to a literary article without reading about how he and Jonathan Franzen had decided that literature’s function is to bridge the divide between two otherwise isolated and lonely consciousnesses. This account fails for me because growing up I never felt lonely. The years before I started to read actively in college were good years, on balance happy years, social years. But I agree with Wallace and Franzen that the magic of literature—and I’ll amend memoir in particular—has something to do with empathy.

“In The Art of Cruelty I spend a lot of time trying to talk about how empathy doesn’t work in linear or straightforward ways. Like: I attempt to make something empathetic; it is empathetic; the reader feels empathetic. It just doesn’t work that way. In Bluets, which is a very private document to me, a lot of people have felt a relationship with the text or had a strong empathetic if—not to me, the narrator—something reflected back by the text. I don’t think it has any relationship to authorial intent. I think it’s a dictatorial impulse that you’re going to produce a certain feeling. You have to focus on your work regardless.”

“People often ask me, ‘Were you doing this to make this effect?’ I would never write trying to produce an effect. It would never occur to me. Because I just don’t think I’m in control in that way. And if I wanted to be, then I should get into Hollywood or something where you’re trying to pull strings in people in a focus-group, scientific way and out of the literature business.”

Maybe the author doesn’t want to write self-help—but that doesn’t prevent the reader from reading it.

Harry Dodge, Black Blob (flow from top), 14” x 11″, 2012. Ink on bristol board.

“I think I’m interested in two really different strains: I’m interested in relational aspects to art and writing, but I’m also interested in the anti- or a-relational. The paradox that things produced in great solitudes—things like Gertrude Stein’s famous writing against the idea of audience. Wayne Koestenbaum has a great essay called ‘Stein is Nice,’ where he says Stein respects her audience enough to leave it alone. There are enough people in my life all the time, I don’t need to write anything that’s trying to hector anyone. I’m just trying to figure out something for myself on the page.”

Empathy is never not particular. I don’t read Bluets and find myself at one with humanity generally; I find myself in relation to Maggie Nelson (her narrator) particularly.

“It’s a longstanding feminist project—it was from feminism’s inception—to remind people that they write from bodies, no matter what they’re writing about. So a lot of feminist criticism and theory from the seventies onward was disabusing us of this notion that the person writing theory or philosophy was unembedded in a body or historical circumstances, because that intervention had to be done to reject the idea of the normal, universal subject pontificating about existence was neutered and non-gendered and non-raced and all that stuff. That was a big project. Combining theory and autobiography stems from liberation movements in the sixties and it’s been with us for quite some time.”

It’s like when Nietzsche locates ”the origin of the German spirit” in “distressed intestines.”

“That’s part of the comedy and allure of reading Nietzsche. Even though he wasn’t speaking about this per se, I think his ideas about genealogy as opposed to history are obviously in line with a certain distaste for the grand-narrative way things are done.

“I’m still very interested in dramatizing in texts the relationship between the so-called abstract and concrete in ways that are unusual. In Bluets, for example, the ghost book for that was William Gass’s On Being Blue: A Philosophical Inquiry, and he makes a lot of puns on blue material, like porn or whatever, and scenes of him masturbating, but it’s more like a wink when you say ‘a philosophical inquiry,’ but no one’s really presupposing that the presence of his jerking-off body would make it not a philosophical inquiry, whereas women have had to contend more with the idea that being embodied is somehow a devaluation or undermining of intellectual thought. So Bluets in part was like watch us go with the female body! and see how it feels differently to you or not. As I say in The Argonauts, there is the spectacle, the oxymoron of a pregnant woman who thinks. It still has a fierce hold on the culture to imagine that if you’re so visibly encumbered by a bodily state your mind might be on par with a certain caliber of thinking—even for me, a pregnant women in public, you’re so transfixed by the spectacle of their pregnancy that you almost can’t hear anything they’re saying. It’s an age-old concept, but I think in the writing you can really screw with it.”

I began this essay by mentioning that Nelson and I had this conversation over a hotel breakfast. But for all the particulars of that morning—I left out the part where our waitress disappeared and Nelson got up to fill her own water glass; I left out the part where we talked about Knausgaard—and of subsequent mornings—I’m leaving out the part where after this interview I moved halfway across the country, started new jobs, and let the transcript sit untouched on my computer for half a year while I worried I wouldn’t remember how to pick it back up when the time came—the circumstances have been eclipsed by the material.

I return to the breakfast now—which the receipt I just found tucked in my copy of The Argonauts tells me consisted of a smoothie, a bowl of oatmeal, and the fruit salad—not so much to tie up narrative expectations as to remind myself that the material was born of two people, the food they ate, and the books they had read, the location of a literary conference, and the just-so calibration of the gravitational constant, for starters.

Harry Dodge, The Volcanologist is Missing, 36″ x 64″, 2013. Oil pastel, charcoal, paint on linen.

Volume 1: Human Contact with Patricia Weaver Francisco

Volume 2: A Tremendous Sense of Purpose with Kao Kalia Yang

Volume 3: I Am Who I Am with Marya Hornbacher

Volume 4: Just the Right Amount of Empathy with Wing Young Huie