An Interview with Writer Mario Bellatin

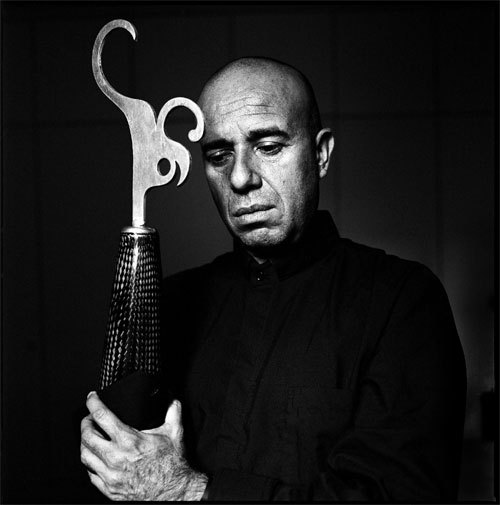

The Mexican writer Mario Bellatin’s latest book to appear in English is The Large Glass, published by Phoneme Media. The novel presents itself as an autobiography, and in doing so scrambles the very idea of autobiographical writing, suggesting that the truth about our lives isn’t in the telling of facts, but in their transmutation. The book also allows Bellatin to continue to play with his mercurial public persona. He is well known in the Spanish-speaking world for his thirty-plus books, as well as for the flamboyant prosthetic limbs he used to wear at events in place of the forearm that he is missing.

The Large Glass offers no straightforward insights into its creator, which is the point. It is broken into three parts, each with a Beckettian feel of perfectly off-key humor and strangely dislocated narrators: a boy whose mother charges customers at a bathhouse to behold her son’s transcendent testicles; a Sufi writer who has an odd encounter with his sheika; and a woman-child whose family was kicked out of their home and now can’t stop lying about who she is. The secret of the novel seems to exist in the spaces between the three stories, and between them and Bellatin.

Mario and I emailed about his new book over the course of the past few months.

—Aaron Shulman

THE BELIEVER: Labeling The Large Glass feels slippery. It could be called an autobiography cloaked by fiction, an autobiographical fiction, or a work that lives on the smudgy threshold between reality and imagination. How would you describe it?

MARIO BELLATIN: I think it’s an autobiography down to its smallest details. Moreover, I think this is how all autobiographies should be. The traditional approach, as it is framed, almost always produces fiction that betrays the truth as a function of the classic format. If I had the time and the desire to do such an exercise, I could rewrite the book in a strictly realistic sense. But it would lose a good part of what a book needs to be for me to see myself honestly.

BLVR: Do you think that there is a brutal honesty embedded in lies? After all, fiction at its core is the art of lying and making things up.

MB: More than lies I think of impostures. And, of course, only a fool would waste the opportunity to express what can’t be said in other spheres when they have created a space to do so. I don’t believe in the art of lying—that wouldn’t go further than Pinocchio or the Boy Who Cried Wolf—but rather in an Art of Wielding False Innocence.

You’ll never see me write a parallel realist book because there isn’t time to do it: Ars lunga vita brevis…

BLVR: What made you decide to reference Duchamp with the title of the novel? What conversation is taking place between his work and yours?

MB: The title has to do with another book of mine called Lecciones para una Liebre Muerta. The name makes reference to another central figure of 20th-century art, Joseph Beuys.

Beuys and Duchamp are two icons who are impossible to refute. They have stayed intact in a supposed hyper-vanguard in spite of the fact that the decades full of their ideas reflect a different way of looking at things. If I stop and think that when Duchamp was growing up there were barely any cars, or that Beuys flew warplanes for Hitler’s air force, I see that it is impossible to speak of advancement or change if we don’t ask ourselves in a radical way if what is presented to us as art and literature are truly that.

It seems that this way of understanding the unnamable is how we should express what traditional forms block us from transmitting. The books have titles that are rather like parodies, that seem to mean that that which supposedly is—museums, bookstores, the paranoia surrounding art—in fact isn’t.

BLVR: In your book, you (or one of your narrators) describes “writing as prophecy,” and mentions how previous books of yours have predicted things that later happened. What prophecies from this book would you like to see fulfilled?

MB: The prophecies are secret. They belong to the universe of the author and not that of the reader. Some of them have been terrible. But I don’t want to turn—for others at least—my writing into something esoteric. I think the purpose that every book has is to lead uniquely to writing another book. Like that strange race in which the first prize is to participate in another race.

BLVR: How does having your novels translated into other languages make you feel? Is it another mask for the text?

MB: Naturally it’s a different book. Just looking at the pages, without reading them, I can see this. And I feel that translations fulfill to perfection my idea that books are only platforms so that another creator—in this case, the person who translates—can make their own work. Which they will hide with their own mask.

BLVR: There was recently an interesting dust-up between you and your publisher Planeta. Could you tell me a bit about that?

MB: It’s true. A good deal of the second half of last year I had to confront an abuse related to the truculent publication of what many consider to be one of my most important books [Salón de Belleza, The Beauty Salon].

The point for me, as a creator, wasn’t so much in this particular infringement—which ultimately I could have let happen, since it was a book that was published twenty years ago, and which was going to be read by a new number of readers—as it was in my commitment to my writing in general, above all, to my future writing. In some way, I believe that my work, scattered in different books and plastic actions of various types, is like one unique book, the writing of which I have given a great part of my existence. And this abuse affected all of my writing and I felt that, until that irregularity was fixed, as a person I wasn’t going to feel one with my writing. It terrified me thinking of betraying something to which I had dedicated my life and not be sufficiently able to repair the opprobrium, to count on the moral transparency that is needed to keep exercising my craft. In other words, I wasn’t trying to defend a specific book from the past but an inexistent one from the future. Something that perhaps would never come to exist. I was defending, I think, a vocation, and an ideal.

It was interesting to see what happened during this process. I came to understand, among other things, that in some way my Writer-I had tried to camouflage himself in my own fictions. I saw put into practice that well-known phrase that writers either flee from the world or remake it. It was important that this happened, in spite of the discomforts of all sorts that I had to escape from. I think it was a kind of late baptism, which made me recognize how fundamental writing is to my life. The funny part is that nothing external changed. I kept writing with the same tenacity as always. But my Writer-I, if such a thing exists, isn’t that same as before. Lately I have the feeling that I’m taking on projects that are more rooted and, with the invaluable help of my new literary agents, we’re “cleaning” up the dozens of my books scattered all over the world, which keep being printed without any authorization or with the contracts not only expired but not even with their most basic clauses fulfilled.

BLVR: Where are things now, and did having to deal with the business side of the writing life so directly stimulate you in any valuable ways?

MB: Things ended well on both sides. I felt that with the full return of the rights and the withdrawal of copies I was able to reestablish my commitment to writing. In exchange, I didn’t sue, since many irregularities were demonstrated not just on the moral balance sheet but the economic one as well. And well, I should admit that I used the situation. I sought out the solution, carrying out a series of actions with a performative character. I used social media—to see if it it’s true that they really can achieve an effect of perturbation in the passing of daily events. It wasn’t, in all, wasted time.

Furthermore, on a personal level, I reconnected with people, friends, and journalists that showed solidarity. And looking at the articles published about what happened in magazines with worldwide readership, I now think that the classic, modernist relationship in terms of the manipulation of literature, of art, has changed. I even wonder if this relationship is not only otherwise, but we now find ourselves facing something very distinct when we talk about these categories. What is an author? What is a book? What is a reader? These are questions that are still unresolved from new points of view.

BLVR: Who would Mario Bellatin be without writing and literature?

MB: A few years ago a friend of mine who I’m very close with told me, directly to boot, that if I didn’t have writing I would be a complete idiot. I remember in that moment that her claim alarmed me. For a time I tried to decode its possible implications. Until finally I couldn’t help but agree with her. I even suspect that to not be a complete idiot is one of the reasons I started writing. This is because it’s a labor that I’ve been engaging in, in an uninterrupted way for almost 40 years, and I can’t find a reason, within a rational framework, that justifies performing such a task. And I think that that point, the relationship between writing and idiocy, shouldn’t be disdained or reduced to anecdote. I myself have experienced moments, long ones at that, of idiotic writing, repetitive, obsessive, hermetic, without an end that justifies it. Idiotic writing that, if I hadn’t acted in time, would have led me to spend my days in an institution of the mentally alienated or something like that. And lately, I feel that many aspects of my daily life have very little do with what can happen in my writing. It is as if they were two independent proceedings moving at different velocities. And sometimes it’s not very pleasant to notice the unbalance. Sometimes I think to myself that the time others spend experimenting with and solving the issues of life—one of those being love—in many of which I feel myself absolutely lost, I spend locked away for days at a time with only the company of a dog and my typewriter.

BLVR: You’re known for making things up when people ask about your work—like a fictitious Japanese writer with a large nose who you ended up writing a book about. Will I discover things here you’ve invented? (I hope so.)

MB: Of course. Answering questions is an art. I’m actually about to write a book about this topic. The central point is that when you answer a question you should always have in your mind the possibility of saying exactly the opposite and it would be equally logical or absurd, depending on how you look at it.