This is the second part of a series on lost landscapes by Stephanie LaCava. Read the first part here.

Stephanie LaCava on Isamu Noguchi, J.M.W. Turner, and Lost Landscapes

A little while ago, I became obsessed with a black and white rendering of playground equipment by sculptor Isamu Noguchi. There were five parts to this drawing, the largest, its foundation, a slim pyramid with a zig zag step rod, three descending tiers of swings. Nearby, a conch-swirl slide, minimalist basketball hoop, seesaw, and rings. Their imagined play with light can be seen in the shadows on the ground. Noguchi named the space Playscapes.

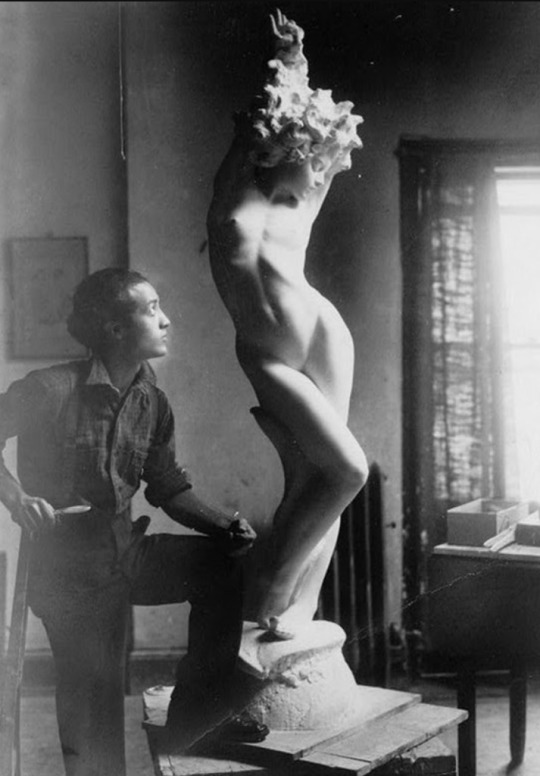

The structure was planned for a park in Hawaii, but realized in Atlanta, Georgia. I always had thought I loved Noguchi, in particular, a photo of him and his Undine sculpture, which I had kept on my desktop and phone. In the image, the young artist is dressed in what looks to be a dungaree jumpsuit. His sleeves are rolled up, tool in hand. He is eye level to the marble bend in his sculpture’s stomach. She’s throwing her hands up, head cast aside. Light comes onto them through a curtained window. It’s an arresting image, but also a false advertisement.

Noguchi worked in such traditional figurative forms like that of Undine until his mid-twenties before moving on to find his signature abstract approach. With this came an avowed commitment to using form and landscape to unite and foster curiosity. His playground designs were created not only as mid-century markers of line and function, but to promote interactive engagement. Here, children could play on the swings or below, in their well-executed shadows. Sadly, the Piedmont Park installation in Atlanta, completed in 1976 was the only one of these playgrounds to be realized in Noguchi’s lifetime. That said, the same childlike spirit is also in the rest of his work.

I thought about taking a road trip to Piedmont Park, except that I already had upcoming plans to go to Detroit, Michigan where there is another of Noguchi’s public works, the Horace E. Dodge Fountain within the Philip A. Hart Plaza, created in the late 70s. While there are many Noguchi sculptures in New York, and an entire museum in Long Island City, I wanted to explore this plaza further from my own home. Noguchi himself grew up in the Midwest, in Indiana. He was born in California and moved to New York as a pre-med student at Columbia University. He would remain there working, though often traveling to projects around the world.

The son of a Japanese father and American mother, Noguchi lived in Japan for part of his childhood before being sent to Indiana for school. I was curious if Noguchi wanted to have his work installed in the mid-west. More likely, I think, it was a matter of commission. He often partnered with other artists and architects. Hart Plaza was a collaboration with the firm of Smith, Hinchman, and Grylls.

Isamu Noguchi at Philip A. Hart Plaza, Photographer unknown. Courtesy The Noguchi Museum.

This plaza is one of only four publicly accessible Noguchi spaces in the United States. Two are in California and one is in Miami, Florida. The Plaza encompasses fourteen waterfront acres located on the bank of the Windsor River where where Antoine Laumet de La Mothe Cadillac landed in 1701. The American Institute of Architects had originally commissioned Eliel Saarinen for a downtown civic center that would include grassy expanses, but production ceased because of WWII. In 1978, Noguchi became involved in the design. Noguchi wanted the plaza be a space where workers could chill after hours and children play on a hot day. The fountain is said to contain three-hundred jets able to create thirty-three patterns of spray. His steel Pylon statue welcomes people to the area.

I went to see the Plaza one morning last week. The area was surprisingly deserted, empty save for me and another couple. The Dodge fountain loomed above, just as I’d imagined it, Sci-Fi, a disk covered in holes held up on two very large legs. The topography throughout the Plaza went up and down and around. It was easy to see why skateboarders liked the park, though they all must have been asleep when I was there.

As when viewing most of Noguchi’s work from this period, the participant is met with dueling impulses. There is a kind of union with calm, primeval forces guided by what’s built on the ground. Then, there is a spark of energy, a swipe at youthful wonder when you look up or down in the way of shadows. Oddly, there did seem to be an eerie suggestion of impermanence, as if the plaza could go the way of Noguchi’s more transient installations, like his set designs for Merce Cunningham and John Cage.

Noguchi’s legacy is defined in part by his work as social space. There was no one there.

I later read that there is talk of changing the plaza, maybe adding a lawn among other things. And it becomes clear that this is another very different example of a landscape that may be lost.

J.M.W. Turner, The Slave Ship (1840). Oil on canvas. 90.8 × 122.6 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

J.M.W. Turner, as renowned landscape painter, is another sort of false advertisement. Few of his works were scenes witnessed firsthand, rather symbolic plays of energy and light. In John Berger’s writings on Turner he cites the correspondence between the artist’s “natural” scenes and childhood memories of his own father’s barber’s shop. There is a sunset: “More profoundly—at the level of childish phantasmagoria—picture the always possible combination, suggested by a barber’s shop, of blood and water, water and blood.”

Turner didn’t sit around waiting for fire and waves; he imagined them as lit abstractions. He liked to use carmine and other unsteady stains, despite warnings about their impermanence. Turner’s paintings grew more abstract as he got older. And nearly two hundred years later, his colors have faded.

Turner has become synonymous with landscape, in part, perhaps because he left so little to illuminate his personal life, only landscape as object. It is known that early in his career, Turner created architectural drawings while studying the metier. His use of landscape as portent is not wholly dissimilar from that of Noguchi, separated by style and time.

Last weekend, I made the drive from Las Vegas, Nevada to nearby Page, Arizona, went through Utah then, back to Arizona, then back to Utah. It was mostly a straight shot, unbroken landscape. First, just flat, rows of tractor trailers roadside, some yellow, others shiny red. One read “Western Express” across its side. Nearly a hundred were all parked together, just like my son stores his model flatbeds by the couch, word choice his, not mine.

There was no visible growth for a while, just flat tan land. Mountains loomed in the horizon line. Standard, cliché clouds. After a stretch, green pops of brush. At first, the sediment in the mountains growing up in size was indistinct, all mottled beige, but the layers became more obvious as I got closer, red and brown. I went by a mound with an H on it, another with an F, and yet another with a sign sticking out that read “For Sale.” This last one was tiny.

I think of Marfa and the power struggle over safeguarding the untouched land. Then, Detroit and a potential clash of interests, that could result in destroying another kind of space.

Across the border in Utah, the sky is striking, a pastel wash. If you turned up the saturation, the sky becomes supernatural-electric-“Damn.” Better as a suggestion, pale sandy spectrum. The rocks fall in until they go black. And then, the landscape changes to mammoth silhouettes and clear sky; creatures sleep.

In the morning, while surveying the land, I saw a jack rabbit, size of a dog, with tall black-edged ears. He made his way stirring up sand. Tarantulas ran in this dust, no snakes to be seen. There are nearby slot canyons, much photographed in their land-locked aurora borealis glory, hot fantasia colors.

There are some flowers here, rangy yellow dandelions and some bright blue thing. I saw a soft purple bush. The land in Utah is mostly neutral and green, though, colonies of those tufts. That childlike curiosity that you can stoke in a city with form is on high alert here. I gave my son a new fleece in olive green, orange, and tan. “Dinosaur colors,” he said. Maybe so.

Strangely, there is no red, no carmine, save for an anachronistic fire hydrant I saw yesterday. Turner’s fires have no place here.

Don Delillo’s Point Omega, that plodding rhythm, gentle swipe at art, arresting when it addresses landscape, addresses all of this: “The desert was outside my range, it was an alien being, it was science fiction, both saturating and remote, and I had to force myself to believe I was here… extinction was a current theme of his. The landscape inspired themes. Spaciousness and claustrophobia. This would become a theme.”

J.M.W. Turner, Sun Setting Over a Lake (1840). Oil on canvas. 91.1 × 122.6 cm, Tate Museum, London.