An Interview with Artist Saskia Wendland

Many will never make the effort to meet their heroes. Blocking the way is a great psychic chasm between desire and fulfillment, between the imagined and the real. If the distance seems too great, a letter might never be sent. A number might never be called. A move might never be made.

When I met the German artist Saskia Wendland at a dinner in New York City, she told me a story from her past: about twenty years ago, she had made the call, sent the letter, and she had fulfilled a desire. She had reached out to her hero, the famously reclusive painter Agnes Martin.

Although Wendland lived in Berlin, Martin’s work had moved her and she wanted to get closer. The trip to New Mexico was more about going to the source and meeting the woman responsible for the great art Wendland had seen in books. There was very little documentation. There was nothing to get. It was the sort of story you tell a stranger at dinner.

—Chris Cobb

THE BELIEVER: Can you tell me the story again? The story about how you met Agnes Martin?

SASKIA WENDLAND: Sure. It was at the studio of a painter friend of mine in 1995. I was twenty-two and came across Martin’s Schriften [(Writings translated into German)].

I borrowed it and from that moment on I was kind of “inhaling the thoughts.” It became like a bible to me.

So, I actually met her first through her writings, and then through her paintings, which maybe is uncommon, since people usually first encounter an artwork and then after start to read about the work and the artist.

Later, I found the book Who is Who in American Art, and I looked up her name, address, and phone number.

BLVR: You just called her out of the blue?

SW: Yes. I remember her voice on the phone—very warm. She was a bit surprised, and said something like, “Sure you can come by, but Germany is far, far away. Just call me back when you’re down here in New Mexico.”

BLVR: How far was it?

SW: There are about 9,000 km (5,592 miles) between Berlin and Taos.

BLVR: That is far.

SW: Luckily my cousin’s friend was staying in Santa Fe at the time. I was able to stay with her.

BLVR: So it’s plausible that she might not have believed you would actually come all that way?

SW: Well, as soon as I arrived in Santa Fe, I made sure to call her again. We made an appointment.

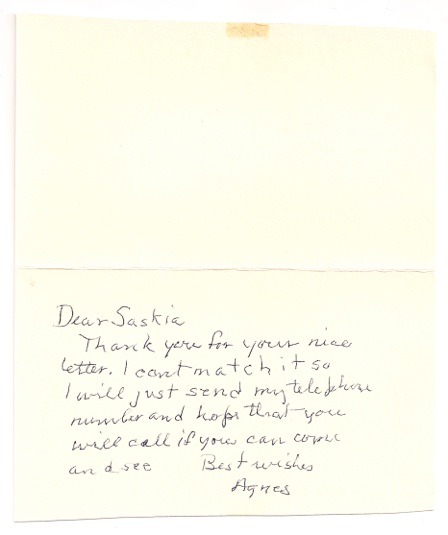

The letter from Agnes Martin to Saskia Wendland, courtesy Saskia Wendland.

BLVR: Was she hard to find?

SW: I took a bus to Taos and got off at a station, not knowing exactly where to go. I asked a random woman at a gas station nearby. She knew, and gave me a lift to the residency where Agnes Martin was staying. It was on March 26, 1996, a few days after her 84th birthday.

BLVR: When you finally got to her home was there a sense that she wanted something from you, or that she was getting something from your coming to visit?

SW: We met in the morning, around 10am. I think I had a water. It was a quiet place. My feeling was that the visit wasn’t of any importance for her.

BLVR: Do you mean that she was hard to read?

SW: Yes, she was hard to read. But she was still open to meet. After about an hour and a half, she said she needed to leave and go to her studio. At that time she still spent four hours a day in her studio!

It seemed like everything came together—the way she painted, the way she thought and lived and her appearance—the way she was standing in front of me. That was an amazing experience. It felt very honest. And that is something I deeply admire.

BLVR: Can you talk about what you mean about honesty in connection to art?

SW: Honest in the sense of a deep investigation of the work. What I learned recently that Martin was a strict editor of her art. She destroyed a lot of her drawings and paintings. She was inspired by grids and lines and fully committed to her project. That dedication seems very honest to me.

BLVR: Did you see her studio at all or did she not take you inside?

SW: No, I didn’t see her studio. But that’s ok. A studio is a very intimate space. What I know about it I’ve learned through texts and books. I would have been surprised, if she would have had me in her studio—a young student that she had just met for the first time.

BLVR: Did she think you were an obsessed fan? Was she friendly?

SW: I am not sure what she thought of me. I was so young. My English was quite poor, and I was so excited to meet her.

BLVR: It sounds like the beginning of a David Lynch film. Was she nice?

SW: She was very kind and friendly.

BLVR: Apparently she was a famous hermit and she lived alone for most of her adult life.

SW: I do recall her space being modest. It was rather small, not many things around. She was sitting in a rocking chair. Behind her, on the wall, she had hung a carpet. It was quite a simple place.

BLVR: Did you get the feeling she was happy out there in Taos?

SW: She seemed to me very much at peace.

BLVR: What is your clearest memory of her?

SW: Probably the moment I wanted to take a picture. It was in the end of our meeting that I asked, whether I could take a picture of her. She agreed and stood in front of her apartment.

She was standing there like a little girl, hands on the sides, asking me, how she should stand, and whether she should change her clothes—she was wearing jeans, a leisure shirt and sport shoes. I, of course, wanted not to change anything. And I remember hardly being able to press the button.

I took one picture with my Contax and one Polaroid.

BLVR: You say you “took” her picture, but you also said you gave her something?

SW: I brought her daisies, which she liked. I also brought her a small notebook from the former East Germany. I had a collection of those and thought she might like it—just horizontal lines.

BLVR: And then?

SW: She asked me, what kind of art I was making and I remember showing her some Polaroids that I took on a trip to New York City and New Mexico.

I recall a moment in our conversation, where I mentioned that I felt that I didn’t have enough time to make work and that I am rather slow worker. She responded by saying, regardless, “keep it in your mind” (even when I’m not working).

She seemed very young to me in a way. Of course, she was 84, but her expressions felt young. Maybe it is a thing around that age, where expressions of old people start to seem youthful again. I mean young in the sense of pure and honest. Her movements were slow and calm, and her eyes were warm and open.

Agnes Martin in front of her home in Taos, New Mexico, by Saskia Wendland.

Saskia Wendland especially would like to thank: Miriam for connecting her to Gabriela; Gabriela for being so welcoming in Santa Fe; Randolph for taking her on a ride on his motorcycle across Santa Fe; Kathleen, who introduced me to Writings by Agnes Martin; and Yael.